![]()

Chapter 1

Reality Is a Model in Your Mind

In this model of Reality, there are three main postulates with four component segments each. When working with each part to make a point or call back to a specific statement, I’ll refer to the parts by 1c or 3a designations as listed in the introduction. This will save space and this shorthand notation will tie different parts of the book together.

Postulate 1a: reality Is a Model in Your Mind

I was commuting home in a Washington, DC, metro bus on a cold, wet, and dark night in Northern Virginia in 2008, reading a Nature magazine (Nature 428, 1 April 2004, 470–471, doi:10.1038/428470a) when I came across an article about Asperger’s syndrome that described how people make mental models in their mind of people they know and are getting to know. People with this mild form of autism spectrum disorder have difficulty updating or creating a unique model of other people with input from the subtler forms of human communication—that of (primarily) nonverbal communication. What is especially difficult for people with Asperger’s syndrome is how much of casual interpersonal communication is nonverbal in nature.

At the root, context, tonality, and body language are important and may determine whether we like a speaker or not. That will then influence if we accept their message or not. Lacking the same real-time feed of the nonverbal components of communication that others expect by default, Asperger’s syndrome sufferers face difficult social situations. The core of this discussion springboards off the more basic concept of the mental models of others—and the world—that we make in our own minds.

As I read through this article, I asked the question—what about the world around us isn’t all, at its simplest, a model in our mind? All we know and can ever know comes through our senses and builds a picture of reality in our memory.

A Model by Any Other Name

What is a model?

Most of the weather forecasting that you hear on radio, see on TV, or find on an app come from what are called computational or numerical models. In a given programming language, a programmer and a meteorologist have worked together to create as realistic of a mathematical picture of the atmosphere and the land/sea below it as they can. This is done in as much detail as computing speed and available memory will allow (both are getting cheaper and more abundant by the day).

Meteorologists and programmers put all the known physical equations into the numerical model and make approximations as needed. Approximations are needed to keep tomorrow’s forecast from taking a year to complete. The programmers include as much land detail as makes sense with the resolution of the model. For example, if the imaginary cubes one is calculating of atmosphere are really large, the Rocky Mountains could be represented by a long tall rectangle. If the calculation cubes are smaller, these mountains might be modeled as a series of simple mounds. If finer yet, the mountains could include finer details like peaks, ridges, and specific canyons.

Unfortunately these model representations of the weather right now are incomplete. Weather measurements at the surface are made at airports, large and small, and other networks, some volunteer, some university, or privately run. Measurements of the upper atmosphere (the rest of the volume of the atmosphere) are made even less frequently (normally twice a day) and only at major airports. All the variations in pressure, wind, temperature, and moisture happening between where and when those measurements are made go unobserved.

On top of how sparse this data is, there are times that errors happen. Instruments go out of calibration and glitches in communication insert errors into this already (uncomfortably) thin data.

Most programs need to work with gridded data—that is data or measurements that are all made at regular distances from one another north-south and eastwest and vertically up into the atmosphere. Since large and small airports and other measurement networks are never in a nicely space grid, we need to interpolate between the real measurements to create this gridded data. If measurements are not made at all the same time, we need to adjust/interpolate between the observation times as well.

When all this is done, we feed this data into computer models that then initialize or start computing using this current snapshot of the atmosphere. Our initialization is often very shaky. To keep errors from building up too quickly, the programmers can use the forecast made by a previous run as input (this earlier forecast is not weighted, or considered as important, as the new data). They can also use climatological norms to keep the models on track.

Summing up, we have sparse data, interpolated data, data that may have errors in it, approximations in the physics, and simplified representation of the land and sea. It is amazing that the weather forecasts are as good as they are.

The Models in Our Minds

As an analogy, this is very similar to what is going on in our minds. We take in data and make a model of the world around us.

It is widely accepted that we have five senses. That’s not really true, but it has been repeated in textbooks and popular culture for many decades. Those main five senses are sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. You also have hunger, balance, taste buds in your esophagus, and even your intestines (responsible for assisting in insulin release). There is the sense of your own internal mental states. Your sense of touch can be further divided into a temperature sense, a sharp-stab feeling, the sense of pressure, and the like.

These senses, be they five or eight or more, are very derivative. They rely on the proper functioning of the human brain to be meaningful. If you suffer a high fever, take certain drugs (legal or otherwise), contract some diseases, or develop a tumor in the brain, you will have a difficult time piecing together what you are perceiving. If you had a long-term breakdown of the physical systems of the brain, you would have difficulty making sense of the narrative reality you experience—for example, the narrative of your life or those around you.

Even when functioning correctly, the brain is always looking to make patterns out of the incoming sensory data. We need to “see the lion through the grass” to survive.

Or make out the code of letters and numbers in a captcha (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) to sign up for a new e-mail account.

Our brains have a hardworking pattern-recognition function which produces solutions, even in cases when we have very little information arriving from our senses. We can sometimes, erroneously, see a human shape that startles us in our darkened room or a voice that seems to emerge from a gentle whisper of wind in a quiet forest. Our brains put the pieces together to create human forms and sounds from very minimal sensory input. This is an important brain function that helps us survive within a world filled with other human beings. Ghost sightings and supernatural spookiness, therefore, can be explained by the normal functioning of our brains.

Further our perceptions are easily tricked by optical illusions and (by design) audio/video-compression formats. Audio and video-compression techniques use clever algorithms to deliver only the information we need to our senses from the music we want to listen to or the movie we want to watch—all without using too much expensive or limited bandwidth. We’ll explore some of these phenomena and techniques now.

Sight

All of the senses are very derivative, but the one that most people rely on heavily for their grasp of reality is sight. We have the perception that our eyes give us a perfectly in focus, three-dimensional, full color, and full-motion view of the world. It would seem strange to consider otherwise.

That perception of perception is wrong. We receive only a fraction of the information we think we do from our eyes.

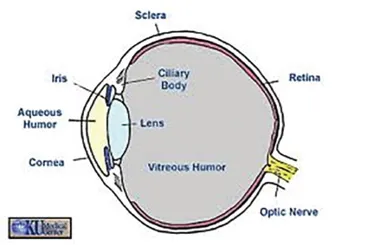

As you may remember from high school biology, the eye works by focusing light that passes though the cornea and lens to a bunch of cells in the back of the eye on a tissue layer called the retina.

These cells do not work like the pixels in a digital camera (like that found in a DSLR or your smartphone). Some cells detect brightness. Some color. Some identify edges (they fire when brighter and darker regions ...