![]()

Chapter One

The Roman Empire in 518

The General Situation

Anastasius left his successor Justin I a mixed heritage. He deserves full credit for having ended the Isaurian problem for good. Similarly, he had reinstated Roman naval supremacy on the Red Sea so that commerce between Rome, Africa and India flourished under him and brought a windfall of customs duties to the state coffers. The victory over the Persians in the war that lasted from 502 until 506 and the building of the fortress of Dara/Daras opposite the Persians at Nisibis secured the eastern border until 527, so it is clear that Anastasius’s policies in the east can be considered to have been a great success. He was ready to listen to his military commanders when they recommended the fortifcation of Dara. The Persians realized how well placed this fortress was and it was because of this that it became their prime objective to destroy and/or capture it, as we shall see.

Reforms in the fields of administration, taxation and coinage made under Anastasius meant that the imperial administration probably worked better then than at any time during the late Empire because corruption was kept to a minimum so that the taxpayers were protected from the abuse of the rich. Under Anastasius the civil service consisted of men who were known for their learning, ability and experience, so it is not a surprise that the civilian administration worked well to support the state apparatus and its military forces. The end result was that the state coffers were full. Anastasius left his successor 320,000 lbs of gold. However, Anastasius’s nominations to high military posts were not quite so successful and sometimes even disastrous, for example the appointments of his relatives Hypatius, Pompeius, and Aristus, and that of Vitalianus as Comes Foederatum. But this would not have mattered had Anastasius not made serious mistakes in his religious policy.

In retrospect it is clear Anastasius’s greatest mistake was the support he gave to the Monophysite/Miaphysite interpretation of the Henoticon of Zeno and the exiling of the Patriarch Macedonius, because these were used by his enemies against him. The making of these mistakes resulted from Anastasius’ own personal religious beliefs. He made the situation worse by denying annona to the foederati in the Balkans and by keeping the coemptio (produce sold at fixed prices for the army) also in effect in the Balkans. The Comes Foederatum Vitalianus used these three grievances to raise a revolt in the Balkans which united the foederati, the comitatenses, limitanei and peasants in the Balkans under his rebel flag. The naval defeat suffered by Vitalianus in front of Constantinople meant that after 515 Vitalianus no longer posed a serious threat to the capital, but at the time of the enthroning of Justin I much of the Balkans was still in his hands. At that stage it was also clear that the Roman imperial authorities could not defeat him militarily. The principal reason for this was that the Romans had lost most of their remaining regular native infantry forces in disastrous campaigns conducted under the leadership of Anastasius’s incompetent relatives against Vitalianus. In 518 the Romans simply did not possess enough combat-ready forces to defeat the rebel. The solution to the problem had to be a negotiated settlement, and this was realized by Justin I, and surprisingly easily accomplished.

The period from ca. 395 until 518 had seen a rise in the numbers of combatants involved in wars and battles so that the development to employ ever larger numbers of men saw its height at the battle of the Catalaunian Fields in 451. However, it did not end then. The Romans continued to use large armies until the reign of Anastasius, but by then the general quality of these was quite low so that during the reign of Anastasius the cavalry was clearly the queen of the battlefield. The employment of cavalry forces meant that the numbers of men in battles became lower because the maintaining of cavalry was more costly than that of infantry and because it was also more difficult to assemble cavalry forces than it was infantry. The massive culling of Roman armies during the last years of Anastasius’s reign meant that his successor Justin I had fewer men available for combat when he took the reins of power in 518. Thanks to the massive hoard of gold in the state coffers Justin I could have raised more men, but this did not happen, for reasons unknown. Justin I and Justinian I clearly relied more on the bucellarii, foederati and foreign mercenaries than any of their predecessors. Perhaps they just did not believe that it would be possible to recreate an effective regular army out of native recruits.

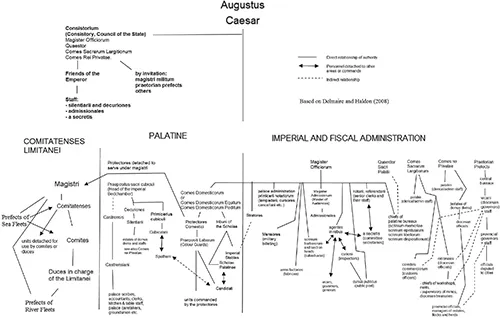

Roman Society, Administration and Military in 5181

At the apex of Roman society stood the emperor with the title of Augustus. Actual power, however, could be in the hands of some other important person like a general or administrator or family member, the best examples of which are the roles of Justinian under Justin I and Theodora under Justinian I. There still existed senates in Rome and Constantinople, but the former was now in Gothic hands. The Senate could be included in the decision-making process when the emperor (or the power behind the throne) wanted to court the goodwill of the moneyed senators. However, it could also be bypassed when the emperor so desired. Late Roman imperial administration was divided into three sections: 1) Military; 2) Palatine; 3) Imperial and Fiscal Administration.

Roman Armed Forces in 5182

Sixth century Roman armed forces consisted of the imperial bodyguards (excubitores, scholae, domestici),3 praesental forces (central field armies), comitatenses (field armies), limitanei (frontier forces), bucellarii (private retainers), foederati (federates) and other mercenaries, and temporary allies, in addition to which came the civilian paramilitary forces.

Most regular soldiers were volunteers, but conscription was also used when necessary to fill up the ranks. The foederati and bucellarii were all volunteers. Because of this their quality was usually higher than the regulars. During this era the effectiveness of the regulars suffered badly from arrears of payment and from the corruption of officers. It was largely because of this that the bucellarii formed the main striking forces. The two principal reasons for this are: 1) most of them were recruited on the basis of their ability; 2) they usually received their salaries in time.

The Roman field army consisted of two groups: 1) The two praesental armies stationed in and around the capital as central reserve; 2) the regional field armies (Army of the East, Thrace and Illyricum). Justinian changed the structure to create a new regional field army for Armenia within a year of his accession and after the reconquest also for Spain, Africa, and Italy, one each. The bulk of the new Armenian Field Army consisted of the retinues of the Armenian nobles. Field armies were usually commanded by the magistri militum.

The limitanei posted along the frontier zones were regular soldiers commanded by duces (dukes) or at times by comites rei militaris (military counts) or magistri militum (masters of soldiers). Justinian created new units of limitanei for the reconquered areas in Africa and Italy, and presumably also for Spain.

The foederati originally meant treaty-bound barbarians, but by this time these were usually fully incorporated into military structures so that their overall commander held the title of Comes Foederatum (Count of Federates). The exact difference between the foederati and symmachoi (allies) is not entirely clear, because there seems to have been quite a bit of a grey area in this respect and for example the Arabs could be considered either foederati or symmachoi. However, there is one basic distinction that can be observed which is that the foederati were considered permanently treaty-bound while the symmachoi retained more freedom to negotiate their position so they could also consist of temporary allies.

The bucellarii were basically private retinues consisting of persons with known combat abilities that any wealthy person could employ, but in practice the emperor exercised full control over these troops. The best bucellarii forces obviously served under those who had an eye for talent and enough money to hire it. Belisarius was clearly the best in this respect. The bucellarii not only had an important role in combat, but also in keeping discipline. A large force of them enabled their commander to impose his will on the other officers in situations in which their loyalty was suspect. Belisarius had 7,000 men at the height of his career. The military hierarchy of the greater households consisted of: 1) the overall commander (efestōs tē oikia, majordomo), 2) a treasurer (optio); 3) officers (doruforoi/doryforoi); 4) privates/soldiers (hypaspistai). The flag-bearer of the bodyguards (bandoforos, bandifer) may have been the second-in command, but this is not known with certainty. The commanders and officers of the bucellarii were also often used as commanders of regular armies and divisions.

Basic tactics and military equipment remained much the same as before. Infantry tactics were based on variations of the phalanx with a clear preference for the use of the lateral phalanx or hollow square/oblong array, while cavalry tactics were based on variations of formation with two lines. Phalanxes consisted of rank and file formations of heavy infantry in which there were typically 4, 8, 16 or at most 32 ranks of heavy infantry footmen. Light infantry was placed behind the heavy infantry, between the files, or on the flanks as required and could also be used for harassment and pursuit of the enemy. The phalanxes consisted of smaller units the most important of which were the mere – divisions (sing. meros) consisting of at most about 7,000 men, about 2,000–3,000 men moirai (sing. moira) and about 200–400 men tagmata (sing. tagma). If the army consisted of less than 24,000 footmen it was deployed as three phalanxes (mere) and if it had more than 24,000 it was deployed in four phalanxes (mere). The standard way to use these was to deploy the phalanxes side-by-side either as a single line or as a double phalanx (heavy infantry units divided into two lines of four ranks, or two lines of eight ranks). The cavalry was typically posted on the flanks and the reserves for both infantry and cavalry were posted behind the front line where required. The phalanxes could then be manoeuvred to form hollow square/oblong, oblique arrays, rearward-angled halfsquare (epikampios opisthia), forward-angled half-square (epikampios emprosthia), wedge (embolos/cuneus) and hollow wedge (koilembolos), convex (kyrte) and crescent (menoeides). The Peri Stragias/Strategikes (34) suggests that it was also possible to deploy one, two or several lines of phalanxes in depth. The smaller units could also manoeuvre on their own to open up the formation for enemy cavalry/elephants to pass through, or to form a wedge or to form a hollow wedge, or double-front (which in practice usually faced all directions), etc.

The general fighting quality of infantry of the period, however, was very low at the time Justin I took the reins of power so that its ability to manoeuvre and form the arrays mentioned above was very restricted in practice. The infantry consisted mostly of men with no combat experience and its morale was very low because it had been repeatedly defeated. It was therefore prone to flee at the first sight of any setback suffered by the cavalry, so that its ability to protect the cavalry was very limited. Because of this Urbicius had recommended the use of protective devices around the infantry hollow square already protected by wagons and ballistae-carriages during the reign of Anastasius. The infantry of the early sixth century required extra protective measures against enemy cavalries. Neighbours could not provide infantry recruits that could readily be converted into Roman infantry forces. The Romans had to train the men to fight as heavy infantry formations. The Romans did employ the Slavs and Moors as footmen and their combat performance was usually very good, but these consisted of light infantry which was not well-suited to serve in heavy infantry roles. The Isaurians inside the Roman Empire were also recruited into the Roman infantry, but once again they were more useful as light infantry in difficult terrain or during sieges than as line infantry, as the following discussion makes abundantly clear. This means that there was no alternative available for the Romans than to train natives to fight in the heavy infantry phalanxes if they wanted to possess infantry able to influence the course of the war.

The Roman heavy infantry consisted of se...