![]()

Part I

Defining London’s Urban Character

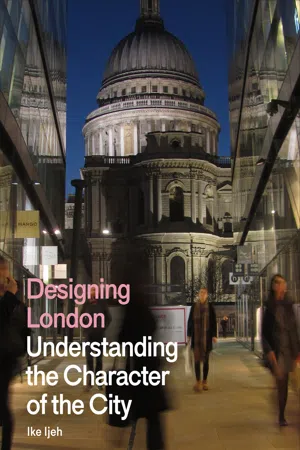

2 People walk through Jean Nouvel’s One New Change (2010), a new retail, leisure and office development behind St Paul’s Cathedral (1710).

Human Capital: Understanding London’s Character

How does one define the character of a city? Can we assess it in the way we assess human personality? Can a city be kind? Can it be selfish? Can it be wise? Can it be cruel? And if we do decide that cities can be assessed in this way, what is London’s character and what makes it different to Adelaide, Berlin, Kolkata or Denver? Paris is known as the ‘City of Lights’ because of its illuminated monuments, its early municipal adoption of street lighting and, more obliquely, because of its intellectual role during the Age of Enlightenment. These are all elements which inform popular perceptions of the city’s luminous character to this day. New York is allegedly known as the ‘Big Apple’ because of midwestern resentment of the city’s perceived greed in consuming a disproportionate bite of American wealth, energy and culture. Few New Yorkers would argue with this aggrieved depiction of a city character seared with rapacious vigour. Rome is called the ‘Eternal City’ for obvious reasons relating to its antiquity and age. And London’s most popular colloquial epithet is the ‘Big Smoke’, an unflattering reference to the appalling pollution the city endured throughout much of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries. But do these glib, titular labels really give us anything more than a superficial snapshot of what really makes a city tick? If we concede there is more to London than pollution, then what constitutes the ‘more’?

VILLAGES

In order to define and understand London’s character, we must first look at how the city developed. London was founded by the Romans 2000 years ago in the area where the City of London stands today. This is the oldest part of the capital and by and large constitutes its geographical centre. But it is important to note that London did not expand in a steady, radial, concentric fashion to occupy the 610 square miles it measures today. It was a choppy and uneven accumulation of neighbouring towns and villages in a messy process dragged out over several centuries.

After the City itself, first to be consumed was Westminster, its marshy, Thorney Island core eventually transformed into London’s seat of monarchy, church and state, a twin focal point for the City which endured as the seat of commerce. Next, London snaked along Ludgate Hill and Aldwych to fill the gap between its eastern and western extremities, merging the City and Westminster together beyond the City’s ancient walls. It was not until the 17th and 18th centuries that London was to spread meaningfully again, establishing new districts in Covent Garden, Bloomsbury and Mayfair. But it was the 19th century when London’s expansion, turbocharged by the Industrial Revolution, exploded beyond all previous measure. Outlying westerly districts like Kensington and Chelsea were gobbled up and London spread south of the River Thames for the first time, consuming the neighbouring town of Southwark. This period also saw the origins of suburbanisation in London, with the outlying villages of Islington, Hackney, Finsbury, Lambeth, Shoreditch and Camden all coming under London’s irresistible orbit. The 20th century saw London grow again, sucking up towns even further afield such as Greenwich, Woolwich, Sydenham, Lewisham, Finchley, Walthamstow, Wembley, Wood Green and Ealing, and effectively repurposing each acquisition from satellite to suburb. The long process of geographic growth was only halted in 1965 with the creation of Greater London and the establishment of the green belt to check London’s sprawl. This is when we first saw the city boundaries that still apply today.

3 Cafe culture in Seymour Place, Marylebone: despite London’s scale, it provides a concentration of distinct ‘village’ neighbourhoods, each with their own unique charm and character.

The point to this process is that there is not one London, but several. The city is often called a collection of villages and the term is both physically and figuratively accurate (Fig.3). London was never planned as a single entity, it colonised and combined multiple settlements into one varied and gigantic whole like a vast urbanised rendition of a split personality. This has had a unique impact on the city’s character. London offers astonishing levels of diversity between its different districts and each one has a special identity very often unique to itself. Kensington is associated with royalty and culture, Bloomsbury resounds with academia, Camden is home to alternative culture, Spitalfields is famous for its markets, Kew for its gardens and Hampstead for its heath and intellectuals. Of course, every city will have different characteristics to each constituent part. But in London these are more deeply ingrained because the pattern of the city’s development often meant that each neighbourhood had its own independent identity before it was swallowed up. And even after their integration into the capital these independent identities remained, so much so that rather than having one character, London has several parallel characters operating at the same time. Therefore, understanding and respecting the unique and divergent quality of London’s village composition is crucial to understanding the overall character of the city.

DIVERSITY AND CONTRAST

And what, then, of this overall character? A city cannot merely be a sum of its parts or else it ceases to be a city; it must have thematic consistencies that define it as a single civic entity unique from other single civic entities, as the popular epithets at the start of this chapter showed. Consequently, two of London’s strongest characteristics stem from its very village composition, diversity and contrast. London is a resolutely diverse city and its village make-up establishes a pattern of diversity that extends into multiple areas of the capital’s urban fabric. This includes a diversity of architectural styles, materials, colours, street and public space typologies, building forms and soft and hard landscaping treatments. This ingrained lack of uniformity therefore, is also a unique aspect of London’s wider character.

With diversity inevitably comes contrast, and contrast too forms a major theme of London’s urban character. All manner of visual and social contrasts can be found operating within the capital’s urban fabric: rich and poor, new and old, high-rise and low-rise, city and park, formal and informal, regular and irregular, public and private, intimate and open, steel and stone (Fig.4). The Inns of Court encapsulate these principles well, Georgian one minute, Elizabethan the next, monumental one minute, intimate the next, expansive lawns one minute, miniaturised courtyards and passageways the next and so on.

Again, to a degree, all cities will include any number of these juxtapositions as part of their urban DNA. But London’s more pronounced reliance on diversity and predominant rejection of uniformity ensures that the city embraces contrast as one of its most powerful characteristic themes. And herein lies one of the problems for London’s character as discussed in the following chapter. Contrast can be cynically exploited as justification for virtually any kind of development. If a city has a tradition of contrast then it surely does not matter if, for instance, a 60-storey tower is placed beside a Grade I-listed Gothic church, particularly if the planning system is vague and imprecise enough not explicitly to prohibit such a course of action. While contrast can obviously be an effective tool in breeding a dynamic and invigorating cityscape full of unexpected drama and tension – as is often the case in London – it is important not to misconstrue contrast as chaos by manipulating it as a precursor to the kind of inappropriate development that can harm character. The aforesaid planning system should be the statutory arbiter that prevents this from happening but, as we shall see, this is not always the case in London (Fig.5).

UNPLANNED DEVELOPMENT

London has always been an unplanned city. In its long history only one successful grand urban plan was imposed on the city, that of George IV and John Nash’s Via Triumphalis which established much of the layout and character of central London we see to this day (Fig.6). Other grand city-wide schemes, such as Charles II and Sir Christopher Wren’s plans to rebuild London as a great, axial baroque city after the Great Fire of London, inevitably fell by the wayside. Historically, London has grown, and continues to grow, by instinct rather than intent, ruthlessly galvanised by a raw and guttural imperative that demands continuity yet embraces change. This may help explain why London has never been a planned city in the manner of other European capitals such as Paris or Vienna or even Washington DC. Uniquely in Europe and in spite of its overtly imperial past, the historical development of the streets, public spaces and buildings that form London’s urban character has assumed an erratic and stubbornly haphazard form that owes relatively little to the autocratic directives of kings, barons or emperors and has much more to do with London’s tradition of loose and organic planning.

Of course, London does have a planning system. And in many ways, that planning system is intensely onerous and prescriptive, as anyone who has tried to build a house extension or erect an advertising hoarding will painfully attest. Equally, London’s municipal heritage should be a source of great pride and in the LCC (London County Council) of 1889 to 1965, successor to the almost as successful Metropolitan Board of Works of 1855, London had the first dedicated metropolitan government in the world and benefited from waves of programmes of social, housing and infrastructure improvements. But at a strategic level, London’s planning system is fractured and contradictory, with each of London’s 33 boroughs able to set their own planning agendas with no mandatory recourse to each other or the city as a whole. Today, the Greater London Assembly attempts to provide a strategic political overview but has limited powers and offers aspirational rather than prescriptive guidelines. For instance, among historic capital cities London is unique in having no city-wide tall buildings policy and the London Plan (the mayor’s official development strategy for the city) merely calls for tall buildings to ‘enhance the skyline’, an indeterminate platitude open to all manner of abuse and misinterpretation (Fig.7).

4 Throgmorton Street, City of London: London’s dynamic mix of old and new helps ensures that diversity is hardwired into its character.

5 The view from Greenwich Park of the Old Royal Naval College (1669) and the towers of Canary Wharf is typical of the stark manner in which contrast is often handled in the city.

6 John Nash and George IV’s ambitious Via Triumphalis of the 1820s culminates in the formal Waterloo Place and is the only major historic example of the successful implementation of a grand plan for the city.

7 Though recent years have seen a massive increase in the construction of tall buildings in the capital, the lack of an overall skyscraper policy is indicative of the city’s empirical approach to planning.

Historically, this tradition of informal planning has had a clear impact on London’s urban character and continues to do so to this day. The relative lack of strategic specificity and prescription certainly gives London dynamic flexibility to respond to all manner of demographic or economic events, as witnessed by the regeneration of Canary Wharf in the 1980s and the gentrification and creeping commercialisation of much of the East End since the late 1990s. But it also leaves London’s heritage and identity potentially exposed to harmful corrosion and makes it harder to enforce coherent, coordinated visions for the city’s improvement. The canny inscription carved on the Monument in 1677 is just as applicable today as it was 350 years ago: ‘Haste is seen everywhere, London rises again, whether with greater speed or greater magnificence is doubtful, three short years complete that which was considered the work of an age’.

PUBLIC VS PRIVATE

London’s historic lack of political authoritarianism and, as we have seen, its relaxed approach to formal public sector planning have left London’s development, and character, disproportionately exposed to private sector influence, certainly in comparison to other European cities. This tradition of private development therefore plays an enormous role in London’s urban character. Perhaps its most obvious manifestation is the London square, essentially a residential reinterpretation of continental equivalents assembled, in this instance, by means of private speculation rather than public subsidy. Squares are an emblematic part of central London’s urban character but, with well over three-quarters of them the result of private speculation, there are key differences between how they are presented in London and generally on the continent. In Europe, public space was frequently conspicuously manipulated as a device for civic display or political strategy. As the Anglophile Danish architect and writer Steen Eiler Rasmussen observed, a French, German or Russian square would often feature an emotional baroque climax, such as a statue or monument as its centrepiece. He identified a typical English square, however, as ‘merely a place where people of the same class had their ...