- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Explore the evolution of London's public spaces and the forces that shape them. This insightful study delves into the design, planning, and social impact of London's public spaces, from post-war developments to contemporary projects. Discover the complex relationships between designers, planners, and the public, and how these influence the creation of civic spaces.

Learn about the key design intentions behind London's public spaces, the role of designers in protecting their 'publicness,' and the impact of commercialization. Uncover the historical context of state-financed projects and the shift towards landscape and public realm architects. This is for anyone interested in architecture, urban planning, and the dynamic interplay between design and society in London.

Information

1 The Importance of Design

The measure of a city’s greatness is to be found in the quality of its public spaces, its parks and squares.

The term ‘public space’ isn’t very old. Post-war, one talked of the need in cities for ‘open space’, predominantly green, and ‘civic space’, predominantly hard-paved. ‘Public space’ as a term seems to have emerged more fully in Britain in the 1980s and 1990s, with a new emphasis on its ability to attract investment, as well as its civic virtues. Civic public spaces are unavoidably declarative. The government of the day, at whatever level, is involved in creating or preserving room for them, and has a stake in what these spaces ‘say’, even if they are produced by the private sector (developers and their investors).

Public spaces also carry an emotional investment. The local public realm, whether streets or squares or parks, is an extension of our dwellings, where we can meet neighbours on more neutral ground and contain outsiders. Civic public spaces, on the other hand, are cosmopolitan in terms of scale and visitor, and although they can also serve as extensions of our domestic lives and carry our individual memories, they fulfil other functions too – public culture, commemoration, celebration and protest. These enactments can be ‘for’ certain groups more than others, but there is in the term ‘civic’ an implication (in democracies), that any citizen, from the city in question or elsewhere, can in some way participate.

Within the confines of this book, the public realm is taken to be physical, comprising public space and public circulation. Public space here is taken to be hard-paved and civic, because it was, and still is, the province of the architect (fig.1.1). There is of course also digital public space, and informal as well as formal public space. These variants are also found under the term ‘public realm’ but are not discussed here. Even if, however, one is confining a discussion of public space to a particular kind, there are further subdivisions. Matthew Carmona created a useful taxonomy of sub-categories such as ‘neglected space’, ‘twenty-four-hour space’, ‘exclusionary space’ and ‘parochial space’ (one type of user rather than all types).2 These are internal as well as external, and one of the most noticeable changes in the past decade has been the evolution of ‘third space’, internal semi-public spaces, as in the circulation areas of the British Library and the National Theatre, where people who do not use the library (fig.1.2) or the theatre set themselves up for the day to work, use the Wi-Fi, and meet others free of charge.

1.1 Hard-paved civic space outside the Greater London Authority Building (left)

1.2 An informal class in the hall of the British Library

Public space can be formal, that is intentional and designed, or informal, an appropriation of some element of the public realm meant for one purpose and taken over by a public for another. This unplanned-for activity can be trivial, like a rave, or more subversive – a political demonstration or occupation of property, in which the design professions play no part, except perhaps as participants. Within formal spaces, therefore, the highest level of inclusion possible should be aimed for, because the social and physical health of a city is measured, among other things, by the condition and use of its public spaces. They are a barometer of the city’s success or failure in promoting a social environment open and stable enough to tolerate, if not embrace, difference.

Achieving this has much to do with the management of a public space, but also with its design. There is a host of ‘design guides’ produced by both central and local governments which present the design of public space as a spatial problem to be solved spatially, addressing questions of physical access, connectivity, scale, ornament, materials, etc. Certainly, such a meat-and-potatoes approach simplifies things, as with this definition of the urban square:

Square:

A formal public space no larger than a block and located at focal points of civic importance fronted by key buildings, usually hard paved and providing passive recreation.3

This may be sufficient to produce the artefacts themselves, and perhaps the design of public space is simply irrelevant to our current anxieties about the privatisation and commodification of public space, addressing instead the need for a pleasant microclimate and attractive physical features:

[B]eyond offering protection from sun, wind and rain, … the design of the public space needs to be anthropometrically and ergonomically sensitive … [P]hysical characteristics that can contribute to comfort in public spaces include sitting space … generous sidewalk width, trees, shade and shelter, a high degree of articulation with nooks, corners, small setbacks in adjacent walls, and landscape elements such as ledges and planters, among others.4

Beyond such considerations, however, there is a wealth of symbolic meaning to be found in this material expression of a public space, and the way its constituent parts make it clear whether a design is seeking to include or exclude, be cosmopolitan or bespoke. Part of this has to do with the visual cues provided to users about gradations of public and private, and the subtleties of the semi-public and the semi-private, known as ‘porosity’.

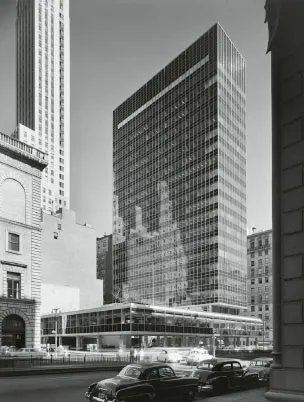

Two spaces on Park Avenue in New York City demonstrate how important the language of design is, and how much it communicates in terms of an attitude to the public. The first is a plaza outside, or rather under, Lever House by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (1952) (figs 1.3 and 1.4), a curtain wall slab block sitting on a two-storey podium occupying the entire site. On the Park Avenue side, the podium sits on columns above a large open plaza that leads to the lobby entrances. Since the completion of the Lever House renovation, the building’s outdoor plaza and glass-enclosed lobby have been used as an exhibition area for the Lever House art collection. Unless there is now extra security, the public can still penetrate beneath the raised podium and on into the plaza, but they may be hesitant to do so. The architectural vocabulary – the line of columns facing onto Park Avenue, the offices above one’s head – says, at best, ‘semi-public’, if not ‘private’, and there may well be no other people there to encourage one to follow suit.

1.3 Lever House, SOM, 1952, New York: an office slab on a podium that fills the site

1.4 Lever House: the semi-public plaza beneath the podium

On the other hand, the space outside Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building (1958), another International Style curtain wall slab, diagonally opposite Lever House, quite clearly states that it is open to the general public (figs 1.5 and 1.6). There is no volume sitting above the plaza itself; it is readily open to the user, even if Mies didn’t anticipate people making themselves quite so at home there. A wide variety of people – construction and office workers, tourists, children – sit on the steps, cool their feet in the shallow reflecting pools and eat lunch on the low walls. The plaza’s design, together with its management, is of a light touch. The minimal gestures made by Mies to articulate the plaza allow people to find their own ways of being there, the essence of cosmopolitanism.

The Seagram Plaza was one of many public spaces in New York studied by the American sociologist, William H. Whyte, for the City Planning Commission. His research culminated in 1980 with the publication of The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, a book and a film describing the ways in which people and public space design meet. His observations and conclusions, based on sixteen years of watching people in public, are as perceptive as they are down-to-earth:

The human backside is a dimension architects seem to have forgotten.

What attracts people most, it would appear, is other people.

It is difficult to design a space that will not attract people. What is remarkable is how often this has been accomplished.5

1.5 Seagram Building, Mies van der Rohe, 1958, New York: an office slab on an open plaza

1.6 Seagram Plaza at lunchtime, with Lever House opposite

Design is thus clearly not an optional extra if one wants a thriving public realm, so it is not a little discouraging to be confronted by statements like this from a 2005 UK government-commissioned report by the think tank, Demos:

In sum, the success of public space is predicated on the way in which it encourages use: diverse use and diverse activities encourage diverse people. Hence public space should form the everyday setting of activities that people can undertake in different degrees of ‘togetherness’, rather than a set piece design.6

As if ‘set piece design’ can’t be part of that ‘setting’ and hasn’t been for centuries. Nevertheless, a kind of inverted snobbery persists about the relevance of design and its ability to address diversity:

The ‘urban renaissance’ agenda appears too concerned with matters of urban design, as well as being distinctly metropolitan in character. The majority of public spaces that people use are local spaces they visit regul...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1 The Importance of Design

- 2 Designers and Their ‘Idea Worlds’

- 3 Programme and Emptiness

- 4 The ‘Right People’

- 5 New Roles for Designers?

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Illustration Credits

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Designing London's Public Spaces by Susannah Hagan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.