![]()

SEEING AND UNDERSTANDING

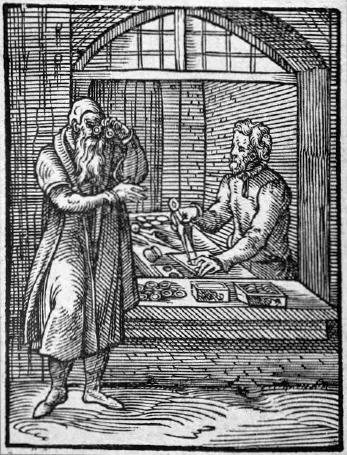

The spread of spectacles also had economic consequences, as artisans began to specialize in spectacle manufacture, causing a rise in production and a gradual fall in prices. The first spectacle makers’ guild was formed in Nuremberg in 1535, and the Nuremberg poet Hans Sachs, whose fame is due mainly to Richard Wagner’s opera The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, included a poem about a spectacle maker in the Eygent liche Beschreibung aller Stände auff Erden, hoher und niedriger, geistlicer und weltlicher, aller Künsten, Handwerken und Händeln (Description of All Estates on Earth, High and Low, Religious and Secular, All Arts, Crafts and Trades, 1568):

I make good glasses

Clear and light

For all ages

From forty to eighty

To preserve eyesight

The frame of leather or horn

The glasses polished

To see through

Clear and sharp

You will find here

What you are looking for.

This description was illustrated by a woodcut by the Swiss engraver and illustrator Jost Amman: it depicts the spectacle maker at his workbench working on a pair of glasses, while a customer tries on another pair from a display.

Perhaps the most famous spectacle seller of the time was Till Eulenspiegel, protagonist of a German collection of stories published in 1510 under the title Ein kurtzweilig lesen von Dil Ulenspiegel, geborn vss dem land zu Brunswick, wie er sein leben volbracht hat (The Diverting Story of Till Eulenspiegel, Born in the Land of Brunswick, How He Spent His Life). Eulenspiegel is a wandering jester who travels around the country and constantly tries out new trades, fails in his economic pursuits and moves on at the end of each episode. The 22nd tale relates ‘how Eulenspiegel became a spectacle maker and could not find work anywhere’. He tells the Bishop of Trier, whom he meets on his way, that ‘the great lords’ have become so learned that they no longer open their books and instead just ‘look through their fingers and do what they please’, setting a bad example for ordinary folk. ‘Our craft is damned,’ he complains, ‘and I go from one province to another and cannot find work anywhere. The decline is so widespread that even the peasants in the country just “look through their fingers” as well.’ This was another one of his jests, because he knew nothing about spectacle manufacture, but the expression ‘look through the fingers’ has become a common expression in German, meaning to overlook or choose selectively what you see.

Eulenspiegel’s tale is realistic to the extent that, from the mid-sixteenth century, real spectacle makers and sellers set up their stalls at markets next to shoe and hat sellers. They were not only master craftsmen but peddlers who sold everything that there was a demand for, including spectacles, from trays hanging by a cord around their neck.

Most of these spectacles were pince-nez with the two frames connected by an iron or copper spring clip and the bridge covered with leather to prevent pressure on the nose. With some of the more sophisticated glasses it was even possible to replace the worn leather padding.

Jost Amman, ‘The Spectacle Maker’, engraving from Hans Sachs, Eygentliche Beschreibung aller Stände auff Erden (Description of All Estates on Earth, 1568).

Reading glasses were so common in the upper classes that in The Book of the Courtier published in 1528, which became a manual for young Renaissance noblemen, Baldassare Castiglione wrote that one should not laugh at spectacle wearers or ask people with a short nose how they balance their glasses on it.

The wearing of spectacles was already known in England in Tudor times. Thomas Cromwell, chief minister to Henry VIII and the mastermind behind the Reformation in England, wore spectacles – a biographical detail that features in Hilary Mantel’s last book of her trilogy on Cromwell’s career: ‘He, Lord Cromwell,’ Mantel writes, ‘thanks God daily for his accurate view of the middle distance. For close work now he needs spectacles.’ Lenses were often imported from Europe, but as demand increased so did the assembling and fabrication of spectacles. King Charles I established the first guild, incorporated as the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers in 1630.

Shakespeare also associated glasses with age. In his famous reflection on the ‘seven ages’ in As You Like It (1599), which starts with the words ‘All the world’s a stage’, he says:

The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank.

Pantalone, the archetypal youthful figure from the commedia dell’arte, is portrayed here as an old man with a stick and spectacles. And in Much Ado About Nothing (first performed in 1612), the confirmed bachelor Benedick questions the manner in which his friend Claudio extols his loved one. He fails to see her beauty, saying ‘I can see yet without spectacles’ – in this case not reading glasses, as he is talking not about reading but more about an understanding of the world.

Jan (Hans) Collaert II, after Jan van der Straet (called Stradanus), ‘The Invention of Spectacles’, plate engraving in the series Nova reperta (New Inventions of Modern Times), c. 1589–93.

Cusa believed that glasses not only enhanced vision but contributed to the understanding of reality. But they could also be used for deception, pretending to see something that wasn’t there. This, at least, is what King Lear meant in the play of the same name (1606), when advising his trusted friend Gloucester: ‘Get thee glass eyes; / And like a scurvy politician, seem / To see the things thou dost not.’ The glass eyes here do not provide a better view or insight but rather distort vision.

Since the Middle Ages, and in Shakespeare’s time as well, eyes have been considered the windows to the soul, and Lear’s spiritual blindness is described metaphorically as poor eyesight. From Lear’s hard-heartedness, leading to the banishment of his favourite daughter (‘Out of my sight!’), to Gloucester’s violent blinding, the dangers of bad eyesight are a recurrent theme. In Shakespeare’s works, sight is often associated with understanding.

This symbolic connection – reading as learning and knowledge on the one hand and as understanding and farsightedness on the other – also gave glasses a negative connotation. Fictional villains such as witches and sorcerers bending over evil-smelling concoctions often wear glasses, as do usurers counting their money. One such usurer is Rembrandt’s rich fool in the painting The Parable of the Rich Fool (1627): an old man sits in a dimly lit room wearing pince-nez and scrutinizes a coin by the light of a candle. The painting refers to the parable from the Gospel according to Luke, which tells of a farmer who collects worldly riches but who is not ‘rich toward God’. Rembrandt’s rich man also appears more interested in money than in the Kingdom of Heaven. To his right is a large money pouch, and in front of him is an assay balance and a box with weights and coins like the one he has in his hand. This rich man, as the parable is conventionally interpreted, represents the wealthy, and his scrutiny of the coin is intended to show how attached he is to his worldly goods. He is not thinking of the hereafter but is firmly rooted in the here and now – and in the here and now spectacles are an attribute of wealth.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Parable of the Rich Fool (The Money Changer), 1627, oil on oak panel.

Jan van Grevenbroeck, or Giovanni Grevembroch, ‘Banker in Eighteenth Century Venice’, 18th century, illustration from the manuscript ‘Gli abiti de’ veneziani’ (The Dress of the Venetians).

By Rembrandt’s time at the latest, spectacles were associated with money changers, usurers and money-lenders – in other words, capitalists and financiers, as we would call them today. And because an above-average proportion of such people in European cities were Jews, glasses became a standard feature of depictions of Jews. Usurers, Torah scholars and yeshiva students were typically shown with glasses, and even in antisemitic caricatures in France during the Dreyfus Affair and in Nazi Germany Jews were disparaged as spectacle wearers.

It is an irony of history that the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza was the most celebrated lens grinder of the seventeenth century. After being banished from his community and from Amsterdam, he settled in Rijnsburg and earned his living by grinding lenses. Even in the modernist era, Spinoza’s profession is referred to metaphorically to highlight the influence of his ideas: ‘All our present-day philosophers, possibly without knowing it, look through glasses that Baruch Spinoza ground,’ wrote Heinrich Heine around 1833.

Lens grinding was a complicated craft calling not only for great skill but a knowledge of optics and mathematics. During the Golden Age of the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, optics and spectacle making flourished. And while political relations between the Netherlands and Spain deteriorated, trade relations remained intact. At any event, Dutch merchants sold spectacles in Spain, and Spanish missionaries are said to have introduced pince-nez even in far-off Asia. There are elaborately decorated Indian models with elephants above each lens, whose trunks reach out to one another on the bridge.

Pince-nez were easier to handle than rivet spectacles but were still uncomfortable. The next stage in the development was to attach an arm to one side of the frame so that the glasses could be held up to the eyes with one hand, a ‘face-à-main’. But these glasses also restricted movement, as one hand had to hold them in such a way that they could be seen through. The next attempt was to hang the glasses over the ears by a cord so that they would remain in place without pressing. These glasses were common even in Japan: drawings from the mid-eighteenth century show spectacle makers are depicted as medical healers.

In Europe as well, spectacle makers were seen sometimes as healers an...