This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The ancient method of growing vegetables in hot beds, used by the Victorians and by the Romans, harnesses the natural process of decay to cultivate out-of-season crops. Jack First has revived and modernised this remarkable technique, and produces healthy vegetables at least two months earlier than conventionally grown crops.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hot Beds by Jack First in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Horticulture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Hot beds are nothing new

The problem of growing crops early in the British Isles and other temperate zones was pondered and answered at least two thousand years ago. If you have ever looked at a stack of stable manure on a cold day, you will have noticed that steam is visible. Clearly there must be a heat source, and this is a fact that was not missed by the Romans. The gardeners of Tiberius (42BC-AD37) had a problem, as their emperor demanded salads out of season. They built beds of stable manure and placed frames upon them. Soil was put inside, and the frames covered with thin sheets of ‘talc’ (translucent sheets that let light through). The manure warmed not only the soil but also the air in which the crops grew.

A hot bed is a warmed, protected environment, created by heat generated from decomposing organic matter, used for producing early crops.

In fact, hot beds of some form were probably in use before the Roman era, as animals were domesticated thousands of years prior to this period. Humans lived in close proximity to their animals, often directly above them in the same building, where they benefited from the warmth of the stock. Seeds in horse feed readily pass into the dung, and hay containing seeds is often mixed with the litter of other penned animals. This litter, probably also containing food scraps thrown down from the household above, would have been taken from a pen or stable and stacked outside, in much the same way as is practised today. Our ancestors would have beheld the bewildering sight of germinated seeds growing on the fermenting stack when all around was covered in snow or ice. Perhaps, in the pre-historical era, this revelation led to the first hot beds. In those harsh times the ability to grow early crops would have considerably improved survival rates.

Down the years many nations have understood and adopted this principle. Up until the First World War Parisian market gardeners were masters of this art, supplying not only their home market with early crops but that of Covent Garden too. One of the French methods, pictured below, involved covering acres of ground with hot beds. Manure was spread evenly over the entire site and rows of frames running east to west were positioned on top. Very narrow paths ran between the rows of frames. In effect, one walked on paths made from manure. As these paths sank, more manure was added, which not only insulated the frames but also heated them up. This process was known as ‘lining’ and was usually carried out during cold spells. With these linings there was no need to have so much depth of manure in the hot bed. The growing medium inside the frames on top of the manure was made up from the previous year’s hot bed, and was usually 10-15cm (4-6") deep.

Hot beds covering acres of ground, over a hundred years ago. The mats used during frosty weather were made of ryegrass.

In the old French medal shown on page 2, which was probably awarded for a rose-growing competition, a figure can be seen in the background working on the hot beds.

Parisian gardeners using hot bed methods would typically broadcastsow radishes and carrots from January onwards. Lettuce plants that had been grown indoors from October were planted on top. Radishes were first to crop and harvest, allowing more light and space for the carrots and lettuces to develop. At this point cauliflowers, also grown from an October sowing, were planted between the carrots and lettuces. The lettuces were harvested next, followed by carrots and finally the cauliflowers.

This all goes against today’s convention of horticulture. Two salads (radishes and lettuces), one root crop (carrots) and one brassica (cauliflowers), all occupying the ground at the same time, produced food in, on and above ground. The French clearly understood the life cycles of various crops, and by clever management of heat and increasing daylight levels produced spectacular results. According to a book by C. D. McKay, The French Garden in England, printed around 1908, the French sent over to London up to 5,000 crates of lettuces with three dozen lettuces per crate, up to 500 crates of carrots with a dozen bunches per crate, plus 100 crates each of asparagus and turnips and 50 crates of celeriac every day – and all between Christmas and March.

So impressed were British growers with the level of French production that they actively sought out these methods and started their own ‘French gardens in England’. Up until the 1930s, many gardening books had a page or two devoted to the hot bed, sometimes referred to as ‘under frame culture’ or ‘forcing’.

The French would stack their manure for a week, then dismantle it and stack it again before making the hot beds, as they were aware that the intense heat generated in the first few weeks would have been detrimental to the crops. So they let this ‘fierce heat’, as they called it, pass off before being used. They would have used long straw, and it is fair to assume that long straw takes longer to decompose, and therefore emits heat for longer. With the much shorter straw of today, such dismantling and restacking would lead to very rapid decomposition and a shortening of the useful longevity of the hot bed. So instead, as we will see in Chapters 4 and 5, the initial ‘fierce heat’ should be tempered by restricting the air supply to the manure. To illustrate: if you take an apple and cut it into small pieces, it will decompose quickly, as a large surface area is exposed to putrefaction, whereas an undamaged apple will take months to decompose. The straw and other materials used for bedding today is not only short but also battered and bruised by mechanical harvesting, allowing more entry points for microorganisms to do their work. It is also probably the case that, as a result of using short straw, today’s hot beds need to be higher than they were in the past, and, because short straw also does not handle as easily as long straw does, stacking and building the beds is harder work.

What matters is that we understand the principle behind hot beds. This principle hasn’t changed, and I have used it to develop my methods and practice to suit present-day circumstances, in the same way that my predecessors devised various methods for their times.

CHAPTER 2

How hot beds work

We now know that billions of microorganisms live, feed and multiply on manure, and that the by-product of all this activity is heat. Typically, fresh manure when stacked or piled high will, within a week or two, attain a temperature of 65°C (149°F) or more. It gradually cools over a period of several weeks or even a few months. The higher the stack, the longer the heat will last.

We also know that these microorganisms require air and moisture, and that a shortage of either will reduce or even prevent decomposition. Too much water will not only cool the manure but also drive out the air that these microbes need. Given the right conditions, a hot bed will produce heat over a long period. More importantly, although the temperature slowly declines, heat is released both day and night. As the microbes’ food supply is exhausted, the heat gradually fades. At this point earthworms enter the manure and not only aerate it but also increase its fertility by way of their casts.

Armed with this information, our aims when making use of hot beds are as follows:

• To manage the manure in such a way as to create ‘bottom heat’ in the bed.

• To manage that heat over as long a period as possible.

• To use it when it is most needed, and that is from January to April, while light levels are increasing.

The main principle to remember is this: the hot bed’s decline in temperature must coincide with the longer days of mid- to late March. By this time the worst of the weather should have passed and longer, warmer days and shorter nights are compensating for the loss of heat in the manure.

Hot bed basics

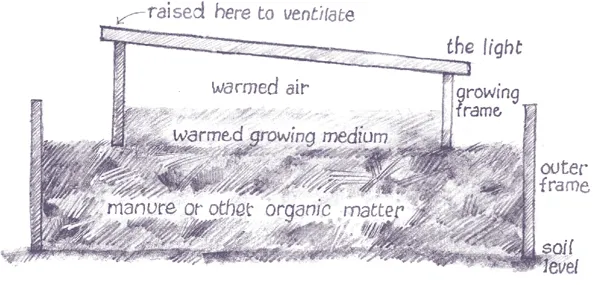

Side view of hot bed with growing frame and light. The outer frame should be at least 180cm × 180cm (6' × 6'); the growing frame at least 120cm × 90cm (4' × 3').

The growing frame sits on the manure, part-filled with growing medium (compost, friable soil or a mixture of materials – see page 39), with a cover of glass or polythene. The frame is usually made of wood with a thickness of at least 2.5cm (1"), which helps to retain the heat and keeps out frost. The cover, known as the ‘light’, or ‘lights’ if more than one, also retains heat and keeps out rain and snow. The growing medium inside the frame is thus kept warm, moist and not saturated, and the air within the frame is also warmed by the constant heat rising from below. Ventilation is provided by raising or removing the light.

In essence, this is how a hot bed works:

• The stable litter or other organic material used in the hot bed drains well, so the growing medium above it also drains well.

This is the same bed as shown on page 10, just one month later, in late March.

• The light covering the frame prevents cold rains reaching the growing medium, ensuring that it is both drier and warmer.

• The heat rising in the hot bed not only warms the growing medium but maintains the air temperature as well.

• The hot bed releases its heat constantly, ensuring warm growing conditions even through the long nights of winter and early spring.

Seedlings in early spring

Most vegetable seeds need ground temperatures of 8-10°C (46-50°F) before germination can take place. These temperatures also need to be maintained for plant growth. It is often the case that gardeners are beguiled by warm conditions in early spring: crops are sown and usually germinate, but returning frost, snow or rain cools the ground to below 8°C, which usually destroys seedlings. Wet soils are not only cold but also take longer to warm up than drier soils, so the situation deteriorates further where the soil is poorly drained. Temperatures generally increase earlier in the south, west and coastal areas, and generally later in the north and on higher ground. The sooner the ground warms up, the longer the growing season will be. Air temperatures closely mirror soil temperatures, which explains why January, February, March and much of April is unsuited for sowings in the open, especially in northern and higher locations.

Germination in sub-zero temperatures

The winter of 2009-2010 was the worst in Britain for 30 years, with many sub-zero days, on one occasion down to -10°C (14°F), yet, from the recordings of a minimum/maximum thermometer, it was evident that at no time did the air within my frames drop below 2°C (36°F). Although not warm, the soil was loose and certainly not frozen solid like the soil outside. The seedlings in a hot bed at times have to withstand these harsh temperatures, but seem to find a way to survive. During the winter of 2010-2011, my sowings were delayed until late January owing to snow. However, these sowings germinated very quickly in early February. On one occasion, although it was sunny in the day, the external temperature was -3°C (27°F), with severe temperatures at night, yet I achieved up to 100-per-cent germination of radishes, carrots, salad leaves, spinach and beetroot, which all cropped well.

Seedlings that appear on the hot bed...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1. Hot beds are nothing new

- 2. How hot beds work

- 3. The advantages of hot beds

- 4. Preparing the hot bed

- 5. Creating the hot bed

- 6. Planning and sowing

- 7. What to grow, and varieties

- 8. Management of your hot beds

- 9. Case studies

- 10. Further possibilities

- Resources

- Index