![]()

AS TOLD BY WOMEN: ST. ELIZABETH OF HUNGARY,

HER FOUR HANDMAIDS, AND THE ICONOGRAPHY OF THE

ELIZABETH MEDALLION WINDOW

(ELIZABETH CHURCH, MARBURG, GERMANY)

LINDA BURKE

For Norma Herrera and Aurora Lopez

mis hermanas en el mundo

Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me. (Matt.25:40)

Almost everything we know about the life of St. Elizabeth of Hungary (1207-1231, canonized 1235)1 was recorded from the voices of women. This truth applies equally to the saint’s example in action and to her teachings in words. Elizabeth’s female witnesses, known to history as the four handmaids, were her closest companions from early childhood to the moment of her death. They delivered their eyewitness testimony in January 1235, well within living memory of Elizabeth’s achievements, and their stories, while of course transcribed by men, were remarkably vivid, circumstantial, frank, and unfiltered.2 Recorded as a collection usually titled the Dicta Quatuor Ancillarum (Sayings of the Four Handmaids),3 hereafter the Dicta, the women’s testimonies quickly achieved a sort of canonical status as a new type of source for the life of a new type of saint.4 They were copied virtually wholesale into Jacobus de Voragine’s much translated collection of saints’ lives in Latin, the Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend, ca. 1272),5 a work that was widely disseminated to preachers and readers both clerical and lay.6 Of all the lives of Elizabeth, only Conrad’s considerably shorter Summa (1232) predates the Dicta.7 Elizabeth’s foundational new model for female sanctity—her lifelong admiration for the Friars Minor, her normal and happy married life,8 her sustained and organized care for the poor,9 her hospital work in widowhood as self-described “sister in the world,”10 her devotion to the sacraments, and her clear and public imitation of Christ—all were uniquely preserved and received by posterity through the voices of these four women.

It has long been recognized by scholars that the Dicta of the four handmaids were foundational to all subsequent treatments of the life of St. Elizabeth of Hungary in writing.11 For example, the Dicta were incorporated almost verbatim into the Life of St. Elizabeth (Das Leben der hl. Elisabeth) by Caesarius of Heisterbach (completed by 1237)12 and into an expanded version of the Dicta known as the Libellus13 (completed before 1244) as well as later biographies. Its adoption into the influential late thirteenth-century Legenda Aurea has been noted above.

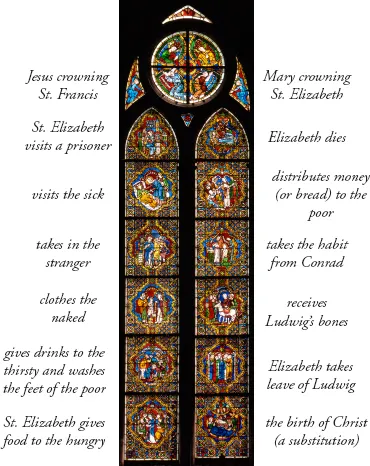

Far less attention has been devoted to the Dicta as key to understanding the details of Elizabeth’s life journey as portrayed in the visual arts, which also served as an essential medium for communicating her spiritual contribution to the world. These pictorial records serve as testimony to the achievements of early Franciscan women and their reception by society at large, just as surely as do the accounts in writing. Much as did St. Francis of Assisi, canonized in 1228, the life of St. Elizabeth inspired magnificent works of art,14 beginning even during her lifetime and shortly thereafter.15 This article will focus on one of the earliest visual monuments to Elizabeth’s life and works, the Elizabeth Medallion Window (Elisabeth-Medaillonfenster),16 hereafter the Window (figure 1), located in the Elizabeth Church (Elisabethkirche) in Marburg, Germany. This double lancet stained glass window (1245-50) has almost never been discussed in English except for two guidebooks to the church available in German-to-English translation (both of which devote a few pages to the Window),17 and in a single article on Elizabeth’s works of mercy in the visual arts, where the Window is discussed only briefly as a prelude to later productions in the genre.18 To my knowledge, no discussion in English refers to the scenes pictured in the Window as in large part a recreation of the voices of women.

figure 1: The Elizabeth Window, Elizabeth Church, Marburg

In German-language scholarship, the role of the Dicta as a primary text for the distinctive iconography of the Window has been treated in some detail, although never (to my knowledge) as the exclusive focus of a study. Providing the most extensive comparisons to date, Renate Kroos weaves together the testimonies of the handmaids along with other influences both textual and visual in explaining the events portrayed in the medallions.19 Discussing the Window, art historians Monika Bierschenk and Daniel Parello refer to the women’s testimonies along with a vast array of other works in various media that provide a historical context and possible models for its program of images.20 My enormous debt to these and other art historians is acknowledged throughout the study that follows. However, the present article differs in several respects from previous works in the field. While not denying the many sources for the complex iconography of the Window, I will focus mainly on the women’s stories in the Dicta as all-encompassing guide to the Window images, from the choice of the six works of mercy as theme for the six left-hand medallions, to many smaller details of the pictures, some connected here for the first time to their origin in the witness of the handmaids. More than previous studies in the field, this article will recognize Elizabeth’s public ministry as “sister in the world” in clear imitation of Jesus (and to a lesser extent St. Francis), as a legacy voiced for posterity by her female disciples.

The study will begin with a review of background material on Elizabeth’s handmaids, her Franciscan-themed vocation, the church built in her honor, and its program of stained glass windows. I will proceed to discuss the Elizabeth Medallion Window both in overview and in detail, with a longer section devoted to the medallion “Elizabeth distributes money (or bread) to the poor” (figure 2). Concluding sections will place the Window in the wider context of art history and developments in medieval women’s spirituality, these last remarks being tentative, as much work remains to be done. I have no intention to minimize the many influences on the complex composition of the Window scenes—ranging from the visual arts in several media21 to politics22 and theology,23 but to focus on a single, vitally important textual source for the images. Except where otherwise indicated, all of the details on Elizabeth’s life as immortalized in the Window and discussed below were originally recorded in the Dicta of the four handmaids.

figure 2: Elizabeth distributes money (or bread) to the poor, Elizabeth Medallion Window, Elizabeth Church, Marburg.

BACKGROUND: THE DICTA

The most important source for all later biographies of the saint, as noted above, is the Dicta Quatuor Ancillarum (Sayings of the Four Handmaids),24 a collection prepared under the guidance of Pope Gregory IX (inspired by an agenda of his own)25 to support her canonization, which he declared on 27 May 1235. This document was a transcription in Latin of the statements made in German before the papal commission of January 1235 by Elizabeth’s four intimate women companions: Guda, Elizabeth’s attendant since she and Elizabeth were five and four years old until just after Elizabeth’s husband died in 1227; Isentrude, also her lady in waiting during her marriage and until shortly thereafter; and Irmgard and Elisabeth, women of humble birth who worked with the saint during the last three years of her life, 1228-31, at the hospital she founded in Marburg. Together, these depositions cover the major themes of Elizabeth’s life story from the time she was brought to Thuringia as a four-year-old Hungarian princess to be raised in the household of her future husband: her early attraction to the Minorite values of poverty and service, her loving marriage to Ludwig the Landgrave of Thuringia, her widowhood as a twenty-year-old pregnant mother of two, her life and death as a hospital sister in Marburg, and at various times, her involvement both passive and active in the faith-based violence endemic to her milieu. Collectively, the Dicta provide a treasury of happenings from Elizabeth’s life and conversation that are known to us only as originally preserved in the accounts of the handmaids.

BACKGROUND: ELIZABETH AND THE FRANCISCAN MOVEMENT

To understand Elizabeth’s pioneering life journey, it is first necessary to consider her lifelong attraction to the Franciscan ideals of voluntary poverty and service to the poor. Skipping over her closeness to the earliest Friars Minor in the German lands, a discussion easily accessed elsewhere,26 I will focus on Elizabeth’s model of an active life performing works of mercy as a “sister in the world,” the life she created with the support of Master Conrad of Marburg, her spiritual advisor from the last two years of her marriage until her death.27 This is the distinctive religious way of life displayed in her Window, as told by women.

Elizabeth’s extreme devotion to the brutal inquisitor Conrad has set her up for negative critical judgments, including my own.28 Despite his zealotry and cruelty, however, it was this same Conrad who encouraged the future saint in social justice actions expressing her Fr...