![]()

Chapter 1: The Irish doctor

For over twenty years, since he first emerged in 1793 as a young artillery officer at a siege in Toulon, Napoleon Bonaparte had been the wonder and the despair of the world. His extraordinary energy had shaken the old countries of Europe to the roots—first France, then Italy, Germany, Spain, Portugal, not to mention Egypt, Russia and Syria—none would be the same after his passing through. By 1814, however, his enemies had been too much for him and he was incarcerated in the Mediterranean island of St Elba, not far from his Corsican birthplace. The diplomats of Europe packed their bags and prepared for a long and enjoyable session of haggling and self-indulgence at the Congress of Vienna. But they had not heard the last of Napoleon.

Aided by devoted adherents, he escaped from Elba in early 1815 and drove north to Paris, gathering more and more enthusiastic supporters as he went. This mesmeric power over the ordinary French people was his strength, not least because it was by far the most populous country in Europe—24 million people against Britain’s 10 million and Ireland’s 5 million (Germany and Italy were still divided into small states).

Europe quickly declared war against him, and eventually fought him to a stop at Waterloo. What Wellington famously called the ‘near-run thing’ cost 40,000 French, and perhaps 22,000 Allied soldiers’ deaths. Napoleon was soon forced to abdicate a second time.

This time the Allies were taking no chances. The most dangerous man in Europe had vividly shown his power during the hundred days since his escape from Elba, and they, particularly the British, were going to make sure that would not happen again. They identified one of the most remote islands in the world, a tiny victualling post in the middle of the southern Atlantic used by ships travelling to and from India. That was to be Napoleon’s new place of exile. Furthermore, the island was going to be policed by as many ships and soldiers as might be necessary to ensure that any escape plans, such as those mooted by Bonapartist refugees in America, should come to nothing.

On board the Bellerophon, the ship used to transport Napoleon and his entourage away from France, was a young Irish surgeon, Barry O’Meara, who was about to embark on the adventure of a lifetime. We join O’Meara on the first leg of the long voyage from Europe to Napoleon’s prison-island, thousands of miles away.

Late in the afternoon the doctor came on deck for fresh air. The heavy Atlantic swell had made most of the new passengers quite seasick. He had spent many hours in the stifling heat below, tending to those who were ill. It was now a beautifully blue, cloudless evening and there was a moderate fresh breeze. With the measured step of an experienced seaman, he made his way up to the poop deck, where he joined a small group of his fellow officers.

The conversation turned inevitably to the dramatic events of the previous days. Suddenly all those facing the stern stood to attention and removed their caps. The doctor turned and saw the Emperor coming towards them. He was accompanied by marshals and generals but, even though they surrounded him on all sides, there was still the sense of a respectful distance being observed. As one of them recalled later, although obviously a prisoner, ‘Napoleon was in fact still an Emperor aboard the Bellerophon. The captain, officers and crew soon adopted the etiquette of his suite, showing him exactly the same attention. The captain addressed him either as “Sire” or “Your Majesty”.’

After he had climbed up to the deck and nodded to the young officers to be at ease, Napoleon leaned against the rail and for a time gazed down at the clear water and then to the horizon. Eventually, turning back to the group, he noticed the doctor for the first time.

‘Are you the chirurgien major?’ he asked, addressing him in French. In Italian O’Meara confirmed that he was. In Italian also, Napoleon continued: ‘What is your native country?’ ‘Ireland.’ ‘Where did you study your profession? ‘I studied in Dublin and later in London.’ ‘And tell me, Doctor, which is the best school of medicine?’ ’For anatomy Dublin is best. London is best for medicine.’ ‘Ah, you only say that because you are Irish!’ ‘No, no, Sire—bodies are much cheaper to buy in Dublin, so our anatomy and hence our surgery is much better.’

Napoleon smiled at this reply and then changed the subject. ‘Where have you seen battle?’ the Emperor asked quietly. ‘I have fought, Sire, in Sicily, Egypt and. more recently, in the West Indies.’ O’Meara told him briefly of some of the more memorable battles in which he had been involved and then, in somewhat greater detail, of the capture of the 74-gun French flagship, the Rivoli. ‘You appear to have been remarkably fortunate in your sea battles.’ ‘Yes.’ ‘The Rivoli was a great loss.’

Napoleon wanted to know more about Egypt and the doctor told him of the rescue of a garrison under siege in Alexandria 1807. To his surprise he discovered that Napoleon had watered and fed his horses in the very same stable where he himself had bivouacked at Aboukir.

Napoleon laughed loudly at this, and afterwards ‘recognised’ O’Meara when he noticed him, and occasionally called on him to interpret or explain English terms. Since one of Napoleon’s entourage was ill, O’Meara was frequently in attendance, and Napoleon regularly asked about the patient, and about the malady and the mode of cure.

From these conversations arose a trust between the two men, and eventually an offer that was to set the thirty-two-year-old doctor on a life-changing course.

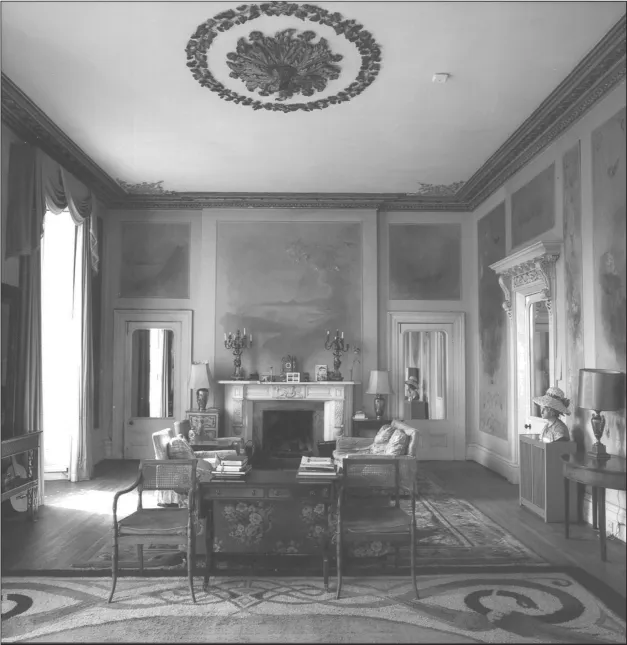

Newtown House today (John Geary)

The interior of Newtown House today, looking much as it would have in Barry O’Meara’s time (John Geary)

Barry O’Meara

Barry Edward O’Meara, third child of Jeremiah and Catherine O’Meara, was born in 1783 in the elegant southern suburb of Dublin, then called Newtown on Strand and now known as Blackrock. He had two elder brothers, Healy and Charles. Some ten years later a sister, Charlotte, was born.

The O’Mearas were comfortably off. Like so many middle-class Protestant Irish, Jeremiah had held a commission in the British army. He had seen service in North America. Later, for ‘seizing with his own hands two of the leaders of an armed mob in the North of Ireland, who afterwards suffered the fate they merited’ he was granted a pension. Then he met and married a beautiful young woman called Catherine Harpur, whose family, recalled O’Meara, owned ‘much land in the counties of Queen’s County and King’s County’. She herself had a substantial income and as the family grew they could afford a large domestic staff. In addition, she employed her own unmarried sister Heather to act as governess to the children. They got on well with their equally comfortable neighbours in Newtown and could count the young Lord Edward Fitzgerald, cousin of Charles James Fox, who later became Britain’s Foreign Secretary, among their many friends.

By 1798, however, when Barry was fifteen, the world was a dangerous place. The British struggle against Napoleon’s French army had been long and not very successful; a detachment of French had attempted an invasion of Ireland in 1796, and again three times in 1798; the 1798 Rising caused thousands of Protestants from the south-east to flee to Wales before it was brutally crushed.

In Dublin the medical schools were working hard to fill the great demand for doctors for the army and the navy across the globe. But neither the army nor the navy could afford to maintain the age-old restrictive distinctions between the learned, hands-off physician and the rough and ready surgeon. The services needed men who could combine both surgery and medicine and that is what the Dublin schools provided.

One of those taking advantage of the new curriculum was Barry O’Meara, who began his training at the age of sixteen, attending lectures at the newly-established Royal College of Surgeons and at Trinity. With his easy-going disposition and agreeable personality, he made many friends. He was formally apprenticed (as solicitors and accountants still are) to one of the most successful medical men of the day, the city surgeon William Leake, a founder-member of the Royal College of Surgeons. O’Meara had great respect for Leake, speaking of him as a ‘wonderful gentleman, who was able and willing to pass on all his expertise’.

Having qualified in 1804, O’Meara immediately enlisted in the 62nd Regiment of Foot in the capacity of assistant surgeon. In his dark navyblue uniform, with its red edgings, the young man cut a fine figure in Dublin society. He was elected a member of the fashionable United Services Club. The future looked bright. In early January 1805 the 62nd were ordered to Portsmouth. There was trouble in the West Indies but unfortunately, the flotilla sailed straight into a gale, which soon became a hurricane. The ships turned and, one by one, made their way back to Portsmouth. The regiment were put on half-pay and told to await further orders. When none came, Barry O’Meara asked for permission to continue his medical education and attended various teaching hospitals in London, including St Bartholomew’s and Guy’s.

Occasionally he was able to return to Dublin and it was during one of these visits that he met an attractive young girl, whose name and subsequent history have disappeared from the records. She became pregnant and it is quite possible that she died during childbirth—an all too common tragedy at that time. The baby boy, whom Barry’s relatives named Dennis, survived and was brought up in Newtown by his sister Charlotte, with the assistance of the large domestic staff.

Meanwhile, the 62nd Regiment of Foot was ordered to the Mediterranean.

O’Meara’s war

On land Napoleon was uniquely formidable. The Duke of Wellington famously compared his presence on the battlefield as equivalent to 40,000 reserves. His speed, technical mastery and aggression made him the supreme general of his day. By 1805 he had subdued, more or less, the continent and now turned his attention to his last and most formidable enemy—Britain. But a victory by the British navy at the Battle of Trafalgar prevented him from carrying out his long-developed plan to invade. For as long as O’Meara had been a student, the threat of invasion had loomed over Britain and Ireland (Ireland was expected to serve as a soft side-entry to Britain). Martello towers were erected along the exposed British and Irish coasts, and the fervid state of alertness sometimes reached fever pitch. In January 1804, for instance, the Freeman’s Journal reported that ‘an attempt without delay is now hourly expected’; the message was repeated on 17 January, 9 February and 14 February. The Rising of 1798 and the two previous invasion attempts showed that this was no empty threat. There is no doubt that the wave of relief that led to the erecting of Nelson’s pillars in Dublin and London was absolutely genuine.

By 1806, Britain had the most powerful navy in the world and was keen to consolidate control of the Mediterranean. However, there were problems everywhere in the region, especially in Egypt and southern Italy. It was for Italy that Barry O’Meara and the 62nd Regiment of Foot were bound.

Returning, perhaps with relief, to land warfare, Napoleon embarked on the re-annexation of Italy. He ordered his troops south to achieve this. Naples having fallen, he prepared to invade southern Italy itself, judging that he should then be able to take Sicily with ease. The prize this would deliver was greater still. As he said, ‘he who controls the straits of Messina controls the Mediterranean’.

As the French inched down the peninsula, Major-General Sir John Stuart scored an unexpected victory over the invading French force at Maida in Calabria—a welcome boost to British morale at the time. But his failure to follow up allowed the French to regroup and gradually, over the following year, to conquer the whole of Calabria. His indecision and delay would cost the lives of many of his soldiers. Malaria was rife, and most of the men who became infected subsequently died.

Only the small town of Scylla, with its spectacular castle perched high on a rock overlooking the Straits of Messina, just two miles from Sicily and the British army, resisted the French advance. Having laid siege, the French took Scylla at the end of December 1806 and then began to bombard the castle. Within were over 300 British soldiers and 500 local Calabrians, under the command of Colonel Robertson, of the 35th Regiment of Foot, who was determined t...