This is a test

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

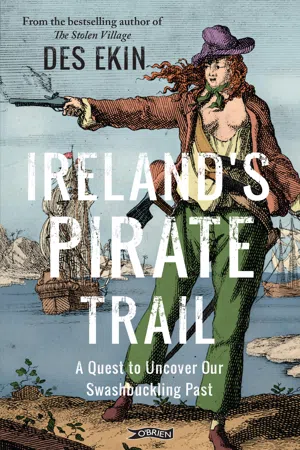

Bloodthirsty buccaneers and buried treasure, fierce sea battles and cold-blooded murders, Barbary ducats and silver pieces of eight.

Des Ekin embarks on a roadtrip around the entire coast of Ireland, in search of our piratical heritage, uncovering an amazing history of swashbuckling bandits, both Irish-born and imported.

Ireland's Pirate Trail tells stories of freebooters and pirates from every corner of our coast over a thousand years, including famous pirates like Anne Bonny and William Lamport, who set off to ply their trade in the Caribbean. Ekin also debunks many myths about our most well-known sea warrior, Granuaile, the 'Pirate Queen' of Mayo. Thoroughly researched and beautifully told. Filled with exciting untold stories.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ireland's Pirate Trail by Des Ekin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Pirate Pilgrimage the First

Dalkey, Tramore, New Ross, Dublin

A journey of a thousand sea-miles begins with a single step.

Just a few minutes’ stroll from my home in south Dublin lies a beach of grey, black and brown shingle. It’s unimpressive in itself, but it commands one of Ireland’s most spectacular views. A couple of miles away, the craggy outcrop of Killiney Hill, dark green and vibrant yellow with wild gorse, is set against a sky that, on this sunny afternoon, is as startlingly blue as a Chinese porcelain vase. The hill rolls chaotically down towards the sea, where, just across a narrow sound, you can see two distant rocky islets inhabited only by seabirds, rabbits and feral goats. The inner one is Dalkey Island. The outer one is known as The Muglins, and it has a special place in pirate history.

It’s a fine day for a walk: breezy and cool, yet blessed with brilliant sunshine that gifts the everyday colours with an unnatural sparkle and glow. I amble along Killiney strand and up a punishingly steep stone stairway from Whiterock beach to the Vico Road. Here, surrounded by road-names rich with the resonance of Italy, I sit on a stone wall to catch my breath. Bramble, heather and furze tumble down the rocks towards Killiney Bay, a sweeping, mezzaluna-shaped inlet that has been compared to the Bay of Naples.

Nearly everyone in Dublin wants to live here. Only the richest do. Nicknamed ‘Bel Eire’, it is home to such stars such as Bono and Enya, people so famous they don’t even have to use two names.

From the Vico Road, I wander into tiny Sorrento Park, a rocky crag offering a fine view over Dalkey Sound and its islets. The sun is now low in the sky behind, but while everything around me is in deep shade, the islands remain brilliantly lit up, as though deliberately spotlighted in a son-et-lumière display. Behind the main island lies the low-slung Muglins islet, with its red-and-white, torpedo-shaped lighthouse. Three centuries ago, however, this island was used for another, more grisly, form of warning. The hanged corpses of two notorious pirates were suspended here, in chains, as a chilling reminder to passing seamen that piracy would not pay. These buccaneers – Peter McKinley and George Gidley – will feature in my first true-life story.

I wander along the coastal road to Coliemore Harbour, a tiny port facing Dalkey Island. It is petite but disarmingly pretty, with brightly-painted rowboats scattered along an ancient stone slipway to a harbour not much larger than a sizeable room. It’s hard to imagine that this once served as Dublin’s main harbour, with merchant ships anchoring in the bay and ferrying their cargoes in by boat. Now, on sunny days, the sailors are outnumbered by the tourists, the anglers and the amateur painters.

Right now, with the little Dalkey Island archipelago vividly illuminated by what seems like its own internal glow, the colours are almost hyper-real: the island’s granite rocks, covered by millennia of moss and lichen, blaze bright in a vibrant honey-mustard colour; the grass varies from a shimmering lime-green to a deep, rich emerald; and the stonework of a ruined church provides its own solemn bass chorus of grey and brown.

Dalkey Island has a long and strange history. Archaeologists once dug up a Bronze Age skull that, on burial, had been ritually filled with shellfish – no-one knows why. In the Viking era, a Christian bishop held prisoner on the island tried to swim across the sound to freedom, but drowned in the attempt.

I find a viewing-telescope and scan its shoreline. Half-a-dozen grey seals lie on the island’s rocks, dozing and stretching as lazily as Sunday afternoon teenagers. Two feral goats stand on the horizon, their shaggy beards and warped, gnarled horns giving them a Pan-like aura. Gulls fight for space, occasionally flying up in an angry flurry to chase away a rabbit, and in the shallows, terns with vivid orange beaks forage for dinner.

For a moment I am blinded by a blast of pure white as a yacht sails by. It passes, and I tilt the telescope towards the separate Muglins islet, where the two grotesque cages containing the pirates’ bodies once swung and creaked dismally in the wind, day and night, night and day, until eventually the metal rusted into powder. Some part of them must remain there, dust of men intermingled with rust of metal, in the earth of this island.

As the afternoon sun disappears, the islet loses its sunny glow and becomes dark, shadowy and melancholy. Two black cormorants stand motionlessly on the rock, their wings grotesquely outstretched, seeming to stare directly at me.

It’s a good thing that I’m not superstitious.

On the Trail of McKinley’s Gold

6 December 1765. Tramore, off the southeast coast of Ireland.

The vessel that shimmered eerily in the sea-mists might have been a ghost ship.

Half floating, half submerged, she wallowed so deep in the water that the waves touched her deck-rails and only her sails were visible to the approaching merchant trader.

The master, a Canadian named Captain Honeywell, later reported that he would have smashed straight into her if he hadn’t spotted her and changed course at the very last minute.

Honeywell, who was on his way to Waterford, hove-to and inspected the mystery vessel. He noted in his log – dated 6 December 1765 – that the stricken ship had three masts and that her top sails were still billowing in the wind, as though straining to free her from the shackles of the immense weight of seawater that filled her hold. Honeywell was also struck by the fact that all her deck-boats were missing and ‘not a living creature could be seen’. Yet the ship remained intact. She had not been wrecked.

A day or so later, eight boats left Wexford to investigate, but the mystery only deepened. The unfortunate ship – the Earl of Sandwich – was already breaking up, and the rescuers were unable to board safely. The vessel was ‘a very rich ship’, they concluded, and had carried not only a valuable cargo of wine but also some well-off passengers. Yet there was not a soul to be seen, alive or dead.

The boatsmen caught their breath when they spotted a black, corpse-like object floating on the waves nearby. When they rowed around to reclaim the ‘body’, they found that it was merely a capuchin – a long, hooded cloak of the type worn by women of quality. It was clear that the victims of this mystifying disaster included at least one affluent female passenger.

It would be another hundred years before the name Mary Celeste became notorious as a symbol of a ship that had been inexplicably forsaken. In the meantime, for those few days in December 1765, the baffling case of the Earl of Sandwich was on everyone’s lips.

As time passed, the sea yielded up some of Sandwich’s cargo. The wine from the dozens of casks that washed up on shore was identified as Madeira, which meant that the vessel had probably sailed from the mid-Atlantic. But what had happened to the women on board? Or the captain? Or her crew?

The investigation took on an even grimmer aspect when an embroidered sampler turned up amid the flotsam. ‘Kathleen Glass,’ it was signed. ‘Her work, finished in the tenth year of her age.’

As exhaustive inquiries continued, the authorities reached their grim conclusion: someone had ‘murdered the crew, and afterwards scuttled her’.

Sandwich disintegrated a few months afterwards, and told its secrets only to the sea. Only four crewmen knew what had happened on board that ill-fated vessel. Their names were Peter McKinley, George Gidley, Richard St Quintin and Andres Zekerman. These men were very much alive – and they were carrying a fortune in stolen pirate silver and gold.

Three days earlier – 3 December 1765

The four pirates had so much treasure stowed in the rowboat, it almost dragged them to a watery death. As they rowed away from the sinking and bloodstained hulk of the Sandwich, its dead weight was like the hand of a dead man, a ghostly avenger pulling them deeper and deeper into the grey-green waves. It seemed to draw and suck the very ocean over their gunwales, into the bilge of their boat, until the ice-cold seawater was rising around their feet faster than they could bail it out.

The shore was still far away. McKinley, Gidley, St Quintin and Zekerman looked at each other. All seasoned seamen, they did not need to do the calculations. Unless they jettisoned some of the treasure, their corpses would join it all on the seabed, so deep down into the grim bladder of the ocean that no light would ever glint off the precious coins scattered uselessly among their bones.

With hearts as heavy as the purses they lifted, they began to scoop out handfuls of coins and hurl them into the sea: Spanish silver dollars, the legendary ‘pieces of eight’ of pirate lore. These casually-tossed handfuls were worth more than they could earn honestly in years, and they were chucking out dozens of them, scores of them, each blighted coin tainted with the blood of the innocent people they had murdered.

Eventually the boat lightened until it rode over the waves instead of ploughing through them. They had lost much of their money, but the trade-off was that they just might survive to spend the remainder.

The coast of the Waterford estuary, at first grey and miasmic in the winter mist, began to resolve and assume a shape. Rocks and trees. Greyish-brown sand. Grey-green grass. It looked grim in the winter night, and yet never had any land seemed so welcoming.

Straining at their oars, they pulled hard against the current until they felt the first rough kiss of the shingly sand against the sea-beaten wooden bow. They hauled the craft up to safety and looked at each other in disbelief. They were exhausted and soaked to the skin. Two of them were bleeding from sword wounds. Yet they had done it. They had stolen a fortune, a king’s ransom, a Midas’s hoard. Bags and bags of milled Spanish silver dollars, of golden ingots, of gold-dust. They had stolen so much that they couldn’t even carry it all away.

Their landfall was merely a temporary stop. They knew there was an English fortress at Duncannon, a little further into the estuary, and they had no wish to be stopped and searched by a naval patrol while carrying two tons of pirate silver. Under a canopy of stars, the four men hauled 249 sacks of coins further up the beach, beyond the ...

Table of contents

- Reviews

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Map

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I: East by Sou’-East

- Part II: South by Sou’-West

- Part III: West by Nor’-West

- Part IV: North by Nor’-East

- Acknowledgements

- Source Notes

- Other Books

- About the Author

- Copyright