- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

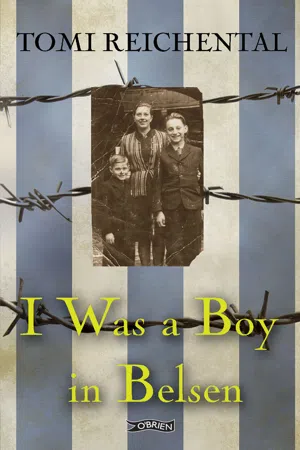

I Was a Boy in Belsen

About this book

'In the last couple of years I realised that, as one of the last witnesses, I must speak out.'

Tomi Reichental, who lost 35 members of his family in the Holocaust, gives his account of being imprisoned as a child at Belsen concentration camp. He was nine-years old in October 1944 when he was rounded up by the Gestapo in a shop in Bratislava, Slovakia. Along with 12 other members of his family he was taken to a detention camp where the elusive Nazi War Criminal Alois Brunner had the power of life and death.

His story is a story of the past. It is also a story for our times. The Holocaust reminds us of the dangers of racism and intolerance, providing lessons that are relevant today.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

NORMAL LIFE CHANGES

Chapter 1

• • • •

Our Home in Merašice

We lived in Merašice, a small, Slovak village in the region of Topolcany, that was home to just seven hundred people. It was a typical village, with the one pub and the Catholic Church providing the entire social life for the locals. My father frequented the pub in order to keep up-to-date with all the news. There were no newspapers, so information was best secured over a beer or a slivovitz (plum brandy). The pub owner, Mr Varga, usually sat and drank with his customers while his wife did all the work. Infrequent visitors, who were on their way elsewhere, were immediately offered food by Mrs Varga – she was a first-rate hostess. From what I remember, the pub was always open; there were no particular hours and the door was never locked. Anyone who passed by always nipped in for a drink and a chat. My father used to say, ‘Even the horses have learnt to stop outside.’

News and gossip were also gleaned from the parish priest, who was a great friend of our family; my parents particularly enjoyed playing cards with him. The old church was probably the most striking building in the village, its simple Gothic interior dating all the way back to 1397, and the steeple was the first thing a visitor would see as they approached the village. Father Harangozo was a small, stout man, whose constant kindness and acts of charity – and partiality to enjoying a few drinks – made him very popular as a neighbour. He lived in a small house beside the church with his sister Marguerite, who acted as his housekeeper and secretary. Aside from his parochial duties, he also taught religion in the local school. A Hungarian, he was delighted with the fact that my educated parents could talk to him in his own language. Of course, his busiest day was Sunday when the church bells rang out summoning the relevant villagers to mass. They would emerge out of their houses in their best clothes. After mass the men headed in groups to the pub, while the women headed home to make the dinner.

My grandparents’ shop was the only decent one for miles around. Far from big, the shop was basically a small room with a counter that separated the public from the small living area out back. It was a mixed hardware store that provided everything from flour, sugar, needles and thread to paper, glue and whatever the busy housewife needed to clean her house. If you wanted something more than this, maybe a new outfit or a pair of shoes, you had to take the single daily bus to the next town. My abiding memory of the shop is how every single item was accounted for and had its own special place. It was always pristine – the dust, imaginary or otherwise, being swept out the door several times a day. When, on the rare occasion that my grandfather, or Opapa, as we called him, was out of a particular product, he would solemnly promise the customer that he’d order it immediately and have it for them within the next couple of days. Never less than professional, he addressed every single customer, regardless of age and status, by their proper name. No slang words were uttered here, nor any kind of casual familiarity. Opapa was an efficient man and his business was a perfect reflection of his character.

He was rather strict, yet we were very fond of him, in spite of himself. My brother, Miki, and I would visit him at work in order to be given sweets, never more than one or two each, as a bribe to leaving him in peace. He only ever dressed in black from head to toe, including his black hat and black moustache. His strictness extended to his religion too. Accordingly, we had a local shoket (butcher), who served the Jewish community. He visited us every couple of weeks to kill our chickens and cows in the kosher way. On Friday nights for the Sabbath meal, the family would wait until Opapa took his seat first. Miki and I were always on our best behaviour because we simply had to be. There were no arguments or fooling around. Instead, our energy was focused on our prayers and our food. The meal had to be completely finished before we could leave the table, and even then we had to ask Opapa for permission first.

Our grandmother, Omama, was the exact opposite of her husband in appearance and manner. While he was tall and slim, she was small and plump, cutting an imperfect figure in thick layers of clothing that were protected by the frilly apron she wore every day. Her thick, wavy hair was silver grey and her double chin wobbled as she went about her chores. I remember her only as an old woman – she must have been in her sixties at least, but she never stopped working. She looked after the house, did all the cooking and baking, and then would look after the shop when Opapa went to get more supplies. My father was the only one of her nine children who lived in Merašice and, consequently, she spoiled Miki and me, stuffing us, much to my mother’s dismay, with whatever she was baking: poppy-seed cake, cheesecake, jam sponge or apple tart. Sometimes I would visit her just to watch her make rye bread, a typical village fare with loaves the size of a small cartwheel. She’d always make two loaves, enough for several weeks. When she wasn’t too busy she’d entertain me with stories, well-known ones like ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ and ‘Hansel and Gretel’.

My mother was rather liberal in her opinions and only visited the synagogue on holy days. She often slipped us non-kosher food too, like salami or bacon, telling us to hide it from Opapa. She believed in children eating fatty foods during the cold, harsh months of winter. I was a fussy eater and was often sick with colds and frequent ear infections. My poor mother would be forced to spend her meal times trying to persuade me to eat my vegetables. My reasons for ignoring her requests were pretty erratic, and no doubt typical of a young child: ‘I can’t eat this spinach; it will make me green all over.’

My parents’ marriage had been arranged – by whom I don’t know – but it was a happy one. What I do know is that they married on 26 October 1930 when he was twenty-eight years old, five years older than her. They honeymooned in Venice, a rarity at the time. I assume the trip was a wedding present from the Scheimovitzes, my mother’s family, who were all successful professionals, including her sister Margo, who was a dental technician and actually ran her own surgery, very unusual for the time. My father’s side was none too shabby either. His siblings included a surgeon, an architect and an office manager. Father had attended a German college in Slovakia, where he studied commerce and agriculture. He could also speak several languages, but never showed any interest in pursuing a ‘proper’ professional career. When Opapa opened his shop, deciding he was too old to farm, Father was more than content to take over the farm. So it was that Mother, a city girl from a well-to-do family, married a farmer and came to live in a tiny village. As could be expected, things were a bit difficult in the beginning; it took Mother a while to settle into her new life, but eventually she found her feet. It probably helped that she and Father had a lot in common. They were both big readers and also loved music, especially opera. Many evenings were spent around the radio, our only source of entertainment. My parents also enjoyed socialising and Father always had plenty of friends in all types of places. We never saw our parents arguing, but would sometimes notice them not talking to one another for a couple of days, though this didn’t happen very often.

We had a maid who doted on my mother – in fact, they were the best of friends. Mariška, a Roman Catholic, had six children of her own, and her husband worked for a German family. She did the washing and ironing, allowing my mother to concentrate on cooking and baking.

We weren’t the only family in the village to have a maid. There were a few wealthy families in Merašice, and the villagers believed us to be rich too, for various reasons. Firstly, there was the shop; secondly, there was my father’s farm of 120 hectares that employed five local men; and thirdly, our house was just that bit bigger. All the houses around were whitewashed and built of mud, while our house was whitewashed but built of brick. There was also the fact that my mother didn’t dress like the other women, who favoured lots of coloured skirts and headscarves – my mother’s clothes were quieter in colour and neater in style. Meanwhile, my father went about wearing a tie, unlike everyone else too. He also had a 125cc motorbike, our only luxury. I loved to sit on the tank watching heads turn as they heard us approach.

At harvest time Father would lodge every penny he made in the bank and there it stayed until there was a proper need for it. Everything we ate was homemade: butter, jam, white cheese, pastry and bread. During the hot summers my mother made her own ice-cream. She also made liqueurs, boiling fresh fruit over the fire and pouring it into glass jars. In this way our visiting relatives had their pick of pear, plum or cherry liqueur, and even brandy. Between my mother and my grandmother, our family was thoroughly self-sufficient. This meant that there was never any actual money in the house. I’m not even sure that our maid was paid in coin; perhaps her payment was the food that my mother would give her.

So, yes, it was true that we had everything we needed, but it really wasn’t that much. Since our house had only one bedroom, Miki slept on the small couch in the sitting-room while I slept at the bottom of my parents’ bed. Furthermore, while our bed linen, Rosenthal dinner plates, glasses, cutlery and ornaments were undoubtedly all first-rate, they were all presents that my parents had received as newlyweds. Once a year I would be taken to town for new clothes.

We certainly didn’t think of ourselves as being well off, but still, there was an invisible social barrier between our family and the locals, despite my father’s extrovert nature. People only ever addressed my grandfather as Stari Panko (Old Sir), and my grandmother was Stara Pani (Old Mistress), while my Mother was Mlada Pani (Young Mistress) and Father was Mladi Panko (Young Sir).

I loved Merašice. Like its inhabitants, it was self-sufficient. Apart from the pub and the church, there was the school and a whole host of specialised tradesman. There was Mr Perutka, the carpenter, who made my skis and toboggan. He could turn his hand to anything, from a fancy cabinet to a sturdy wheel for a hard-working cart. I can’t remember the name of the blacksmith, but I loved to watch him work as he folded iron like it was pastry. Mr Polackek was the mechanic; he worked on the steam engines that were rented for harvesting the fields, and could also fix motorcars, which were a rarity in the village. Fortunately, he could also repair the water pumps, as there were only three wells in Merašice. These sorts of skills stayed in the same family from generation to generation. If another family wished their son to learn a trade they had to pay the craftsman a hefty sum for the required three-year apprenticeship. Money was scarce, so that was a big undertaking.

Other tradesmen passed through, constantly moving from village to village, to where the work was: the glazier, the man who sharpened scissors and knives, and the man who repaired things like pots and pans. Nothing was ever thrown away, only sharpened and fixed. My parents were very welcoming to these travellers; my mother fed them and my father let them sleep in one of our barns.

There was a second prosperous business in Merašice, apart from farming, and that was the manufacturing of red bricks for the construction industry. The local factory was owned and run by two Germans, Mr Ploich and Mr Shultise. As with just about everyone else in the village, my father got on very well with these two, thanks to his fluency in German.

Our village was such an idyllic place and never more so when, during the summers, my cousins visited from the city, making me realise all over again what a paradise surrounded me. My mother would bring us scoops of her ice-cream in our very own tea house, the small, wooden structure in the back garden which contained a round table and bench upon which eight excited kids could just about fit. If we were still hungry, we had a variety of fruit to choose from – I needed only to stretch out my hand to grab cherries, grapes and gooseberries, and in autumn apples from the apple tree with its spidery branches that dangled low enough for us to help ourselves.

A little stream ran through the village where we’d swim and fish for hours on end. Then we’d return home with tiny fish in the palms of our hands, excitedly ambushing my mother at the door: ‘You have to fry these because we want to eat them for dinner.’

Thanks to the warm weather I went barefoot all summer. I had to be careful, however, when the sun grew fierce as I would inevitably be forced to return indoors, suffering from heat-induced migraines. In between football matches and fishing for dinner, I loved to follow my father around, checking out the crops and then hanging out with the man who took the cows out to pasture. Because I was the boss’s son, he made me whistles from the willow branches that dangled at either side of the stream.

Summer also meant the wondrous smell of fresh flowers in the air. A vast, colourful array of flora grew in and around the village. It’s something that I’ll never forget, that heady scent of perfume that persisted no matter where I stood, and attracted umpteen bees and flying insects. One of my favourite times of the year was harvest time when all of us children, usually half-naked under the blue sky, would run to the fields to watch the big, noisy steam engine work away – a welcome improvement on the horse and plough.

Winters were also special and meant just one thing: snow – and lots of it. It started to fall in November and would cut us off from everywhere else, blocking the roads and making it impossible to travel by bus or car. Even as a young child I appreciated the stillness of the village when the snow served as a sort of muffler against noise. The world seemed like such a softer place under the blanket of white. Then, during the day, it would begin to thaw, only to freeze anew at night, leaving hardened drips, or icicles, dangling from the roofs of the houses. My mother had the carpenter make us a fine toboggan which was bigger than everyone else’s – Miki and I would follow her to the top of the hill, near the church, and then we would all climb on for the breathtaking descent.

Of course, winter also meant Christmas – not that Christmas was actually celebrated in our house. We had our own festival, Chanukah, the festival of the lights, which begins some time before 25 December and lasts eight days; each night an additional candle on the chanukiah is burnt to comm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Prologue

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Introduction from the Holocaust Education Trust

- Introduction

- Foreword

- PART I: NORMAL LIFE CHANGES

- PART II: BERGEN-BELSEN

- PART III: AFTER BELSEN – LATER LIFE

- Epilogue

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- References

- Plates

- Postscript

- About the Author

- Copyright

- Advertisement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access I Was a Boy in Belsen by Tomi Reichental,Nicola Pierce in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.