- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

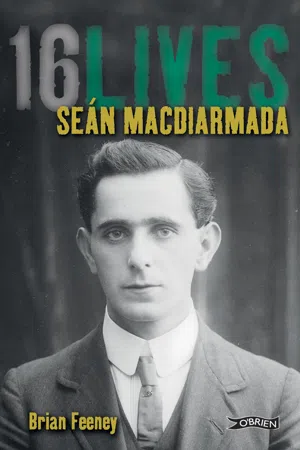

Seán MacDíarmada moved in the shadows, ultra-cautious about what he committed to paper, aware that his letters could be intercepted by the police. Because of this, history has not allocated MacDíarmada the prominent role he deserves in the organisation of the Easter Rising.

This book gives Seán MacDíarmada his proper place in history. It outlines his substantial role in the detailed planning of the Rising, which led to him signing the Proclamation of the Irish Republic: second only to Tom Clarke.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

• • • • • •

• • • • • •

1883 – 1905

A Leitrim Upbringing

Seán MacDiarmada originally aimed to be a schoolmaster. For a clever and able boy, the eighth of ten children of a carpenter and part-time farmer, the chance to become a national school teacher offered an attractive prospect of advancement, a regular income, possibly a rent-free house beside a school, and a pension on retirement. It was also one way out of rain-soaked, poverty-stricken Leitrim. However, the route to a teaching post at the end of the nineteenth century was long and arduous. John McDermott, as he was known until his twenties, stuck at it for seven years, from 1897 to 1904, but the last hurdle, the King’s Scholarship examination, was too high and he could not surmount it.

Aspiring teachers like McDermott followed what was essentially a five-year apprenticeship from thirteen or so, the age when most other children left elementary school, the name for primary school in those days. School, for the vast majority of Irish children in rural districts in the nineteenth, and well into the twentieth century, was a one-room stone building where local children aged five to thirteen sat at rows of oak desks. They were taught together by the ‘master’, a person of some standing in the parish, who strove to bring each year group in the class up to a series of national ‘Standards’ in English, Arithmetic and other subjects like Geography and History.

Bigger schools sometimes afforded an assistant teacher but more often the master was helped by an older boy or girl who aspired to be a teacher. They were called pupil teachers or monitors but they were essentially dogsbodies, filling the inkwells, marking the work of junior pupils and tidying up at the end of the day. They came in to the school early and left late, using the extra time to study work set by the master and to prepare simple lessons for the class, given under the supervision of the master. Pupil teachers were paid a pittance, about £1 a month or less, which works out about €108 in today’s money.

After about five years, the pupil teacher sat what was in effect his or her final examination, the King’s Scholarship. If successful, a ‘call’ to a teacher training college in Dublin followed, but competition was so intense that a mere pass was usually not enough.

The exam was daunting. Florence Mary McDowell, a County Antrim writer and former national school teacher, described in her 1972 book Roses to Rainbows the exam she sat before the First World War:

Teachers were expected to know things. They were not expected to think, but they were certainly required to know. Everything was to be learned by heart: Joyce’s Irish History, British Constitutional History, the Physical and Political Geography of the World, no less, Music, Drawing, Penmanship, Arithmetic and Mensuration, English, Reading, Poetry, Drama, Composition and Literature. One failed the whole King’s Scholarship, a pre-requisite to training in Dublin … if one failed in any one of the ‘Failing Subjects’ English, Arithmetic, Music, Drawing, or the all-important Penmanship.

The sad reality is that McDermott had no chance of passing. The school he prepared in, Corracloona National School, still sits in rural isolation, renovated and modernised on the road from Glenfarne to Kiltyclogher. It is still a one-classroom primary school, and was no place to prepare for the KS. When McDermott was studying there in 1903 his access to the necessary resources must have been severely limited. He took a correspondence course with the Normal Correspondence College in London. Such courses were a very popular way at the end of the nineteenth century for students to gauge their abilities against a national standard and even to obtain recognised certificates and diplomas.1

In McDermott’s case one handicap was the absence of a library in the nearest village, Kiltyclogher, an hour’s walk away. However the lack of available books was not necessarily fatal since a lot of the KS syllabus was based on rote learning. McDermott’s Achilles’ heel was mathematics. It is quite possible that the master at Corracloona, Mr Magowan, did not have either the time or the knowledge to teach McDermott the mathematics the KS demanded, because McDermott took extra tuition with Mr James Gilmartin, assistant national teacher at Corracloona. McDermott told a friend at the time: ‘I hate Euclid and I’m afraid that the old rascal will have revenge on me if he catches me at an examination.’ It was a certainty that ‘the old rascal’ would catch him at the KS because Euclidean geometry was an essential component of the exam, but McDermott did not have to meet Euclid to fail. Records show that it was not only the more esoteric aspects of mathematics that presented McDermott with difficulty: as a schoolboy, he regularly failed elementary arithmetic.

Given that deficiency, the standard of the KS was such that no matter how hard he worked he was never going to pass. In 1904, after struggling for seven years, two years longer than normal, McDermott inevitably failed the exam and saw his hopes of advancement vanish.2 With no skills, no qualifications and no prospects, he was now twenty-one and still living at home with no visible means of support in the poorest, rainiest county in Ireland, a place people had been leaving in droves since the Famine.

Despite his humble background, there must have been some surplus cash available to account for John being allowed to stay on at school for seven years after the usual leaving age. It is probable that, in addition to money earned through carpentry and farming by his father, there was money coming in from family members working abroad, money known in those days as ‘remittance money’. By the time of the 1901 census, when John still had three years ahead of him as a monitor at Corracloona, one brother and two sisters had already left home. John himself, who at this stage of his life was still officially ‘John Joseph’, as he had been baptised, would not be long in following.3

How and by what steps did John Joseph McDermott, from remote rural Leitrim, become Seán MacDiarmada, one of the signatories of the 1916 Proclamation? Are there any clues in his family background or upbringing, or did he acquire all his opinions and convictions after moving to Belfast in 1905?

McDermott had been born in January 1883 in a remote farmhouse at a place called Corranmore in the townland of Laghty Bar in County Leitrim, near its border with County Fermanagh.4 Even today the way to the family home is an easily missed left turn off the road from Glenfarne to Kiltyclogher. In 1883 it must have been little more than a boreen. The thatched stone-built house the McDermotts lived in, now a National Monument, is a hundred metres off that narrow road at the top of what would have been a muddy path. It is built on the foundation of a flat rocky outcrop at the top of a small hill with a good view of the surrounding countryside.

Ten metres from the front of the house, the land slopes away steeply from the exposed rock towards a boggy depression covered with trees and lush grass. Two hundred metres to the right of the front door is a peat bog still being cut today, covering about three acres. To the McDermotts, the land would have offered no opportunity for arable farming. On each side of the house and at the back were small stone outhouses, enumerated in the 1901 census as a cow house, a calf house, a piggery, a barn and a shed. The two outhouses, one on each side of the family home, have been restored like the house itself, but those behind the house are in ruins.

The McDermott home had three rooms, two on the ground floor and a loft converted into a large sleeping space, probably by John’s father, Donald McDermott, using his carpentry skills. It is hard to see how the small-holding could have sustained ten children, five boys and five girls, at the level of prosperity evident in an 1890 family photograph, without the supplement of cash from those skills (which, according to local tradition, are responsible for the pews in St Michael’s Catholic church in nearby Glenfarne). Indeed, Donald McDermott must have regarded wood-working as his primary occupation, because he described himself as ‘carpenter’ in the 1901 census. The 1890 photograph shows Donald McDermott’s wife Mary, two years before she died in 1892 when John was nine.

Not surprisingly, after the body blow of rejection by the King’s Scholarship examiners in 1904 and the realisation that seven years of study had come to nothing, McDermott thrashed around for about a year looking for a different direction to his life, but above all for some means of employment. His first excursion in search of work, following the traditional route of thousands of men from Leitrim and northwest Ireland to Scotland, proved to be abortive. Unlike many others, he did not head for the coal mines or factories of Scotland’s central belt, or Glasgow’s shipyards, or the potato fields of western Scotland, but joined a cousin in Edinburgh doing gardening work.

Of course it was not real gardening as McDermott had no knowledge of that. It amounted to labouring: digging, brushing, sweeping and as McDermott himself said later, ‘raking paths’.5 He did not last long, and soon he was back in the family home where he probably spent the summer helping out on the farm. In October 1904, after the potatoes were saved, he headed to Tullynamoyle in County Cavan to study the curious combination of Irish and book-keeping at night school taught by Patrick McGauran. According to a Kiltyclogher ‘Commemorative Booklet’ produced in 1940, McDermott lodged with a local family at Tullynamoyle during his night school course, which lasted until March 1905. There is no evidence that he was in employment during this period, which suggests that family money must have provided his rent and upkeep.

It’s true that McDermott wrote to a friend extolling the benefits of learning book-keeping as a way to advance his career prospects, but could it be that McDermott went to Tullynamoyle mainly to learn Irish from McGauran? Why else choose to go there, thirty kilometres from his home instead of, say, to Enniskillen, forty kilometres away and on a better road? Or Sligo, much the same distance? It goes without saying that both towns would have offered far superior facilities for learning book-keeping. A century ago Tullynamoyle did not exist as a village: it was a townland. The so-called ‘night school’ must have been a room in McGauran’s house or one he rented in another house. On the other hand, neither Sligo nor Enniskillen would have provided the same opportunity to learn and speak Irish as Tullynamoyle did in the person of Patrick McGauran, who was highly regarded as a native Irish speaker and teacher.

The 1940 commemorative booklet reports McGauran recalling that McDermott was ‘anything but a book-worm’.6 According to the booklet, McDermott at twenty-two was of average height, which would have been about five-foot-six in those days, ‘with strong dark hair, well-marked eyebrows and dark blue eyes’.7 He loved hunting rabbits, and one piece of information betraying something of his political predilections is that, for the purpose of hunting or coursing, he kept a greyhound called ‘Kruger’ (named after Paul Kruger, the Boer War general and later President of South Africa). So it was likely that McDermott sympathised with the ‘pro-Boer’ (and anti-British) position adopted by Irish nationalists at the turn of the century. It’s also noteworthy that he was politically aware enough to choose a name like Kruger for his dog.

McGauran said that the only subjects that captured McDermott’s attention related to Ireland and its language, heroes and history, and he read everything he could find about those topics. He was keen on poetry, ‘especially Irish patriotic poetry’, and the work of Scottish poet Robert ‘Robbie’ Burns. McDermott’s party pieces were Emmet’s speech from the dock and a dreadfully maudlin, saccharine ‘poem’ called ‘The Celtic Tongue’, a lament on the death of the Irish language written by a Fr Michael Mullin from Kilmore in County Galway (who died in Chicago in 1869). Not much about book-keeping there.

According to Fr Charles Travers in a 1966 article, McDermott had ‘a fair fluency in Irish’ from his youth. His mother and father spoke Irish to each other, and at that time older people in the district used Irish almost exclusively, to the point that many of them had difficulty with English when they came into the towns to market.8 The 1901 census records that at the age of eighteen McDermott did not speak Irish, even though his father could, but ten years later McDermott filled in his own 1911 census return in colloquial Irish and by that stage was a fluent speaker. Did he go to Tullynamoyle to perfect the basic Irish he had learnt from his parents at home, or was he illiterate in Irish and went to McGauran to learn how to read and write the language?

Given his subsequent political trajectory the very fact that he took a conscious decision in 1904 to learn Irish is significant. Unlike book-keeping, Irish would not have improved his career prospects. His decision may have been driven either by the prevailing romantic nationalism of the Irish-Ireland movement, namely zeal for all things Irish, whether language, literature or sports, which was going from strength to strength in the country at the time, or...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Reviews

- Title Page

- Dedication

- 16LIVES Timeline

- 16LIVESMAP

- 16LIVES - Series Introduction

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: 1883 – 1905: A Leitrim Upbringing

- Chapter 2: 1905 – 1907: Belfast Republicans

- Chapter 3: 1907 – 1908: The Sinn Féin By-Election

- Chapter 4: 1908 – 1911: Tom Clarke

- Chapter 5: 1911 – 1913: The Volunteers and the IRB

- Chapter 6: 1913 – 1914: The Howth Gunrunning

- Chapter 7: 1914 – 1915: Imprisoned

- Chapter 8: 1915 – 1916: Preparations for a Rising

- Chapter 9: January – April 1916: Orders and Countermands

- Chapter 10: Easter 1916: ‘Everything Splendid’

- Chapter 11: May 1916: ‘We Will Be Shot’

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plates

- Copyright

- Other Books

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Seán MacDiarmada by Brian Feeney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Biographies historiques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.