- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

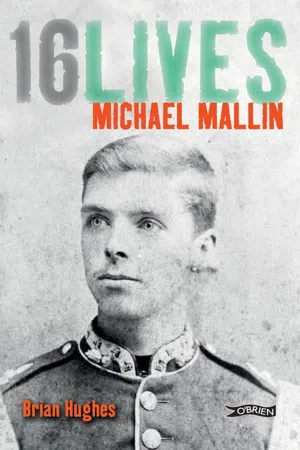

Executed in Kilmainham Gaol on 8 May 1916, Michael Mallin had commanded a garrison of rebels in St Stephen's Green and the College of Surgeons during Easter Week. He was Chief-of-Staff and second-in-command to James Connolly in the Irish Citizen Army.

Born in a tenement in Dublin in 1874, he joined the British army aged fourteen as a drummer. He then worked as a silk weaver and became an active trade unionist and secretary of the Silk Weavers' Union.

A devout Catholic, a temperance advocate, father of four young children and husband of a pregnant wife when executed – what brought such a man, with so much to lose, to wage war against the British in 1916?

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

• • • • • •

1874 – 1889

Family and Early Life

In the months after the execution of the leaders of the 1916 Rising the Catholic Bulletin wrote a series of articles entitled ‘Events of Easter Week’, describing Michael Mallin as ‘Commandant Stephen’s Green Command … a silk weaver and musician, a splendid type of the Dublin tradesman, a credit to the city which cradled him close on forty years ago.’1 This was very much the conception of Mallin in the years following his execution. A contemporary pamphlet on the leaders of the Rising wrote of Mallin: ‘Nor must we forget Michael Mallin … a silk weaver by profession, a musician and an active temperance advocate, he was one of the most sanguine of all the Company Commanders.’2

Of the sixteen men executed for their role in the planning and execution of the rebellion, Michael Mallin is among the lesser known. Virtually nothing has been written about his life before October 1914; he appears in literature about the Rising only after he becomes James Connolly’s Chief-of-Staff. Perhaps Michael Mallin has been overshadowed in history by two figures: James Connolly, the only man higher in rank than Mallin in the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), and Countess Constance Markievicz, second-in-command to Mallin during Easter Week 1916. Mallin has almost become ‘sandwiched’ between these two iconic figures and his own significance neglected as a result.

Michael Thomas Mallin was born into a working-class Dublin family on 1 December 1874 in Ward’s Hill in the oldest part of the city, the Liberties. Mallin’s eldest son has recorded that he often signed his name as ‘M.C. Mallin’, the ‘C’ standing for Christopher and probably a Confirmation name.3 He was baptised on 6 December in the church of St Nicholas of Myra on Francis Street.

Mallin’s father, John, had grown up in the home of his grandfather, also named Michael, at City Quay; his grandfather made parts for sailing ships. John was the son of another John Mallin and Mary Mangan (said to be a daughter or cousin of the poet James Clarence Mangan), and he had a brother, Michael, who died as a young child. John’s mother, Mary, disappeared in strange circumstances – she went missing one stormy night and it was thought that a strong wind had swept her into the river Liffey; her body was never found. Soon afterwards, John’s father emigrated to Australia, leaving his son with his own father. He was not heard from again and it was rumoured that he was murdered in Australia.

John Mallin had married Sarah Dowling around 1874 and Michael Mallin was born that year. Mallin’s mother, who, unlike the rest of the family, was unable to read and write, had worked in a silk factory in Macclesfield, England, but had lost her job when she expressed sympathy for the ‘Manchester Martyrs’ – in November 1867 William Allen, Michael Larkin and William O’Brien were hanged for their role in an attack on a police van in Manchester in September of that year, an attempt to free two prisoners, during which an unarmed policeman was killed. Sarah Mallin had apparently witnessed the attack on the police van. The execution of the ‘Manchester Martyrs’ provoked a swell of sympathy for the movement for independence in Ireland. It is not clear if Mallin’s mother was sympathetic to the cause prior to events in Manchester (she had family in the British army) or if she was moved by what she had seen, but she does seem to have shown support for the independence movement in later life. Returning to Ireland, she worked in Dublin as a silk winder.

Mallin’s mother came from a family steeped in the traditions and culture of the British army, even if she did not share this tendency. Two of her brothers were in the British army, both serving with the Royal Scots Fusiliers. A third, Bartholomew Dowling, had decided to join the priesthood, but instead he met a girl from Connemara on a trip to England and chose to leave his training and get married. At that time it was seen as a source of great shame not to finish one’s training as a priest, and that he left to get married only added to the disgrace. To escape this, he decided to sever relations with friends and family and move to America. Having not heard from her brother for a period, Sarah Mallin decided to go to America to find him; she took her young son, Michael, with her. They seem to have stayed in a house in New Bedford, Massachusetts, for a short period until the missing brother was located.4 Little else is known of this trip.

At the time of Michael’s birth in 1874 the family was living in a tenement building at 1 Ward’s Hill, the Liberties having the highest concentration of low-value housing in the city. In the 1870s Ward’s Hill was characterised by decayed eighteenth-century buildings; fine Georgian houses that had once housed the most affluent members of Dublin’s population had been taken over by unscrupulous landlords whose aim was to squeeze every penny of rent possible from these buildings. Whole families occupied single rooms, heating and sanitation was severely lacking and privacy was almost non-existent. At their worst, Dublin’s slums were among the most appalling in Europe. Infant mortality was high: of eleven children born to John and Sarah Mallin, six survived to adulthood. Of the surviving children, Michael was the eldest of four brothers, Thomas (Tom), John and Bartholomew (Bart) and two sisters, Mary (May) and Catherine (Kate or Katie).

Not all who occupied tenement buildings were completely impoverished: in fact, Mallin’s father, John Mallin, was a skilled boatwright and carpenter and his father, Michael’s grandfather, had a boat-building yard in Dublin, which had been in the family for five generations. The Mallins would have enjoyed a more substantial income than many of those around them, but the poor living conditions made raising a large family difficult.

Mallin’s eldest brother, Tom, worked as a carpenter, while brothers John and Bart worked as silk weavers, sisters Mary and Catherine as a biscuit packer and vest maker respectively.5 According to Tom, Mallin’s father was a ‘strong nationalist and he and Michael had many a political argument’.6 Mallin’s youngest son, Joseph, has described his own recollections of his father’s family:

Uncle Tom was more outgoing than John or Bart. John’s family and his wife were extremely pleasant – no histrionics. … [aunt] Kate, always seemingly gently amused when talking about the family & others. She was amusing about my grandfather [John Mallin]. He disliked any coarse language and if it started would remark he did not like such talk and would leave the company. [William] Partridge noticed that trait in my father.7

The family lived in a number of locations around the Liberties over the years. It was not uncommon for Dublin families at this time to move around the city, often within relatively close proximity, as their financial conditions improved or worsened. In 1889 Mallin’s family was living in Marlborough Street and by 1901 they had moved to a residence in Cuffe Street where they would remain for at least the next decade. Little is known about Michael’s education but he probably attended the national school in Denmark Street, near the family’s home. Like most from his social background, Michael’s formal education was brief and basic and he left school in his early teens.

In 1889, shy of his fifteenth birthday, he was persuaded to join the British army by an aunt during a visit to the Curragh in County Kildare. Michael’s uncle, James Dowling, had served with the Royal Scots Fusiliers for a number of years in India and was then employed as a Pay Sergeant in the Curragh. Michael seems to have been close to his uncle, often spending summer holidays with him. It was during one of these holidays that Michael first became aware of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. The regiment’s band had made a great impression on the young Michael and this is what prompted him to enlist. On hearing that her son had joined the army, Sarah Mallin was worried and angry with him for doing so; he reassured her that it was the musical band that he had joined.8 Michael Mallin joined the 21st Royal Scots Fusiliers in Birr on 21 October 1889 as a drummer boy, signing up for twelve years’ service. Surviving records from his enlistment give a physical description of him as a boy approaching fifteen: he was 4 feet 5 inches in height (he was never to be a tall man), 64lbs with a ‘fresh’ complexion, grey eyes and brown hair. His regimental number was S.F. 2723.9

Notes

1 ‘Events of Easter Week’, Catholic Bulletin, Vol. VI, No. VII (July 1916), p398.

2 Sinn Féin Leaders of 1916, Dublin, 1917.

3 Inniu, 30 Oct. 1966.

4 Mallin family 1901 and 1911 census returns (National Archives of Ireland); Bureau of Military History Witness Statement (BMH WS) 382 (Thomas Mallin).

5 Ibid.

6 Fr Joseph Mallin, S.J., to the author, 13 Nov. 2009.

7 Inniu, 30 Oct. 1966.

8 Inniu, 30 Oct. 1966.

9 BMH WS 382 (Thomas Mallin); Account book of Michael Mallin, Royal Scots Fusiliers (Kilmainham Gaol Archive); Michael Mallin’s British army record (National Archives, Kew: WO/97).

Chapter Two

• • • • • •

1889 – 1902

British Army Career

When Michael Mallin joined the Royal Scots Fusiliers the regiment was on an ex...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Reviews

- Title Page

- DEDICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 16LIVES Timeline

- 16LIVESMAP

- 16LIVES - Series Introduction

- CONTENTS

- Chapter One: Family and Early Life

- Chapter Two: British Army Career

- Chapter Three: Silk Weaver and Musician; Trade Unionist and Socialist

- Chapter Four: The Silk Weavers’ Strike

- Chapter 5: Changing Fortunes; Joining the ITGWU; Character

- Chapter 6: Irish Citizen Army

- Chapter 7: The Eve of the Revolution

- Chapter 8: Easter Week

- Chapter 9: Court Martial; Execution; Last Words

- Chapter 10: Critical Commentary on Mallin’s Rising

- Chapter 11: The Mallin Family; Commemoration

- Appendix 1: Michael Mallin’s last letter to his wife Agnes, Kilmainham Goal, 7 May 1916

- Appendix 2: Michael Mallin’s Last Letter to his father and mother, Kilmainham Gaol, 7 May 1916

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plates

- Copyright

- Other Books

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Michael Mallin by Brian Hughes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.