- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

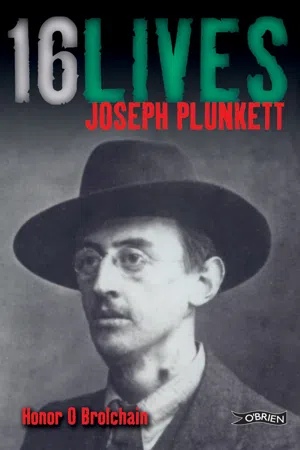

Joseph Mary Plunkett (1887-1916) from Dublin was one of the leaders of the 1916 Rising, the designer of the military plan and the youngest signatory of the Proclamation. A recognised poet, he was already dying of TB when, aged 28, he married Grace Gifford in Kilmainham Gaol, just hours before he was exectuted on May 4th, 1916.

This timely biography, written in an entertaining, educational and assessible style and including the latest archival evidence, is an accurate and well-researched portrayal of the man and the uprising.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

• • • • • • •

1886–1902

The Young Plunketts

WITLESS

When I was but a child

Too innocent and small

To know of aught but Love

I knew not Love at all.

But when I put away

The things I had outgrown

I learnt at last of Love

And found that Love had flown.

Now I can never find

A feather from his wings

Though every day I search

Among my childish things.

Joseph Plunkett

When George Noble, Count Plunkett and his wife returned from their two-year American honeymoon in 1886 Josephine Mary (Countess Plunkett) was already pregnant with their first child. The Plunketts were the beneficiaries of wealth created by their hardworking parents. Their fathers, Patrick Plunkett and Patrick Cranny, had moved from the leather and shoe trade in nineteenth-century Dublin to building on the south side of the city, largely thanks to money provided by their wives, one of whom, Bess Noble Plunkett, had a shop of her own and the other, Maria Keane Cranny, had family money, a dowry. The property built and accrued by Plunkett and Cranny would have come to a considerable amount. It was mostly not intended for sale, but for rental to professionals and civil servants. Count and Countess Plunkett’s marriage settlement included eight houses on Belgrave Road, Rathmines and seven houses on Marlborough Road in Donnybrook, three farms in County Clare and a house on Upper Fitzwilliam Street, No. 26, ‘an address suitable for a gentleman’, and this house was where they lived.

It was comparatively narrow and consisted, essentially, of two rooms on each floor. The basement was mostly used and occupied by the servants, but there was also a lavatory there for Count Plunkett’s exclusive use. On the hall floor Count Plunkett had his study in the front beside the hall door to which he retreated for most of the time when he was at home to continue his work on European Renaissance art, Irish history and politics and his many other areas of scholarship and expertise. Behind his study was the dining room with the painting he thought might be a Rubens over the mantelpiece and behind that room a conservatory. From the hall the elegant staircase led past a beautiful window to a landing and two drawingrooms in an L-shape, all designed and proportioned by the Georgian builder for stylish entertaining. The stairs continued past a bedroom on the return to the two bedrooms on the next floor, one for the Count and one for the Countess. From this floor upwards the style and elegance disappeared and a very ordinary and very steep attic-type stairs led to the nurses’ and children’s quarters, which had a bathroom used by most of the household as well as one room the width of the front of the house and one, half that, at the back. The area behind the house, a garden and yard, was very small in modern terms, not a leisure garden, but an area for the burying and disposal of waste. Behind this was Lad Lane where the Plunketts’ carriage was housed and their horses stabled in the livery stables. Count Plunkett filled the house all the way to the nursery at the top with paintings. He also oversaw the decoration of the drawingrooms and cast the house as a place beautiful enough for children to grow up in, but in the forty years they occupied it the Plunketts did no more to improve or decorate it.

The nursery area at the top of the house was home not only to that first baby, Philomena Mary Josephine (Mimi) and her nurse from Mimi’s birth in 1886, but to all seven children as they arrived, their three nurses and one or two nursemaids until they were all young adults. This does not in the least compare with the four or five entire families in one room which occurred in the terrible and extensive poverty of areas of Dublin at the time, but it must have made some of the individuals in those two rooms ache for peace and privacy at times. It was alleviated by visits to the rest of the house to see their parents once a day or less and a walk every day:

One or two of the nursemaids used to bring all of us children for a walk every day but before we could leave there were seventy little buttons to be done up on my clothes. The walk was always the same, from Fitzwilliam Street along Leeson Street and Morehampton Road to Donnybrook Church and a little way on to the Stillorgan Road, with Jack in the pram and the two small ones, George and Fiona, in a mailcar which was a back-to-back go-car made mostly of bamboo. I had to walk with Joe and Mimi and Moya. Geraldine Plunkett Dillon

All seven children were born in the house: Philomena Mary Josephine in 1886, Joseph Mary in 1887, Mary Josephine Patricia in 1889, Geraldine Mary Germaine in 1891, George Oliver Michael in 1894, Josephine Mary in 1896 and John Patrick in 1897, their mother being attended each time by Nurse Keating, her maternity nurse. Countess Plunkett’s name, Josephine Mary, is repeated with incongruous frequency in the children’s names but, in fact, they were usually known as Mimi, Joe, Moya, Gerry, George, Fiona and Jack. Thirteen months after Mimi, on 21 November 1887, Joe (Joseph Mary) arrived.

The year after the birth of the next child, Moya, in 1889 the Countess organised the first of her famous holidays. These were as much to get away from her children as to get away herself. This one was to Tuam in County Galway where she rented an unfurnished house and had all of the luggage and furniture sent there from Dublin by canal boat to Ballinasloe and from there, in thirty carts, to Tuam. She travelled there with Mimi, Joe and Moya, all under five years old, but she herself spent most of the time back in Dublin leaving the children in the care of their nursemaids and the owner of the house. Joe’s sister, Gerry, was born four years after Joe, in November 1891, and it is to her that we are most indebted for the detailed personal accounts of the lives of all her family, especially Joe, whom she greatly loved.

One of her very early memories was a ‘howling row’, a battle between Mimi and Joe and the ‘horrible’ head nurse. Mimi and Joe told her years later that they were just trying to draw attention to what was going on. They were at the mercy of this nurse and her threats. Joe told her that one of the nurses used to heat the poker until it was glowing red and threaten to shove it down his throat when he cried. Another trick was to push the go-car (precursor of the buggy) out over the edge of the canal and threaten to let go; this was supposed to be for ‘fun’. Gerry’s nurse (each child had a nurse brought in for them) Biddy Lynch was different. She stayed with them for nine years bringing order, affection and pleasure into their lives. In Gerry’s description:

She was kind, sensible, just, clever, intelligent, patriotic (a Parnellite), absolutely reliable, religious, scrupulously exact and honest. She taught us to read and to write and to sing Irish songs, she taught us our religion, she washed us and dressed us, she made our clothes and hats and, in her spare time, knitted stockings for her mother at home in County Westmeath.

Some of the maids lived in, but those who didn’t used to finish work at about seven o’clock in the evening and meet up with their friends, often standing and chatting outside the house. On one of these evenings Joe and George decided to drop light bulbs from the fourth floor nursery window onto the basement area and the maids thought the resulting explosions were revolvers. They complained that they knew they had been noisy, but they didn’t think they should be shot at!

Joe already had what was known as ‘bovine’ tuberculosis by that time, probably contracted when he was about two years old from milk. It is a virulent form of tuberculosis, which attacks the glands as well as the lungs and causes weight loss and night sweats. As a disease it was cloaked in ignorance and myth and even the experts underestimated it as a fatal disease. ‘Bovine’ tuberculosis, transmitted from humans to cows and back to humans is now dealt with by pasteurisation of milk. Joe Plunkett’s temperament was active, interested, humorous and lively but he had to suffer the restriction and frustration of being frequently confined to bed with this illness all through his life. In 1895 another long family holiday, this time to Brittany for three months, was undertaken with the Count and Countess, her mother, Maria Cranny, five children, Mimi, Joe, Moya, Gerry and one-year-old George, and Gerry’s nurse, Biddy Lynch.

By the time he was seven Joe was being taught by a governess along with his sisters, Mimi and Moya. The Countess often sat in on these sessions and not only interfered, but even competed with the children. In the time-honoured manner, governesses came and went at frequent intervals, but it is to her nurse, Biddy, that Gerry gives the credit for teaching her to read and write. It is likely that this also applied to Joe, although it was usual to take boys’ education more seriously and he would have been the focus of attention from both the Countess and whichever governess was there at the time. The Count left the employment of staff and organising children’s lessons to his wife, but he talked to his children as he would to any adult and about the same things – art, history, French, Italian, books, Irish history – and with the same enthusiasm and affection, so they were simultaneously acquiring another type of education.

In the winter of 1896 Mimi was sent as a boarder to Mount Anville School, and Moya and Gerry to the Sacred Heart Convent, Leeson Street while living with their grandmother, Maria, in 17 Marlborough Road in Donnybrook. After her husband’s death she had moved there from Muckross Park, which her husband built for her. The Countess often sent her children off to other houses and schools and this time she had good reason as she had a small baby, Fiona, at home and was pregnant again.

There was a children’s fancy dress party that year given by the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Richard McCoy, and the Countess decided to send her four eldest children, Mimi, Joe, Moya and Gerry. On the day of the party they were taken to a costume hire firm and dressed up, Mimi in an ‘Irish’ costume, Moya in a Kate Greenaway dress and bonnet, Joe as a Gallowglas and Gerry (who really hated the whole proceedings) as the Duchess of Savoy. Gerry found it stilted and not at all about the children, but there is no record of how the others felt. However the ordeal was not over because they were ‘stuffed’ into the costumes again the next day and taken to the Lafayette studios on Westmoreland Street to be photographed both as a group and individually. The result is beautiful and dramatic, but taking photographs at that time was a slow process requiring the subject not to move for a long time, always difficult for children, so they used to put their head and neck in a brace to keep them still. In the end the expense was enormous and the pleasure only for the adults.

In 1897 the family rented a house called Charleville in Templeogue on the outskirts of Dublin and the children were sent there with Biddy Lynch. What was supposed to be a few months turned into a year with visits from their father and, occasionally, their mother. This meant that Mimi, Joe, Moya and Gerry were now missing school, but they did have a governess, Mademoiselle Ditter, whom Gerry describes as:

… small and dark, a wild creature and a terrible tyrant, and she always abandoned us if possible. She was supposedly French but in fact she came from Alsace and had a strong hatred of the French. She used to teach us how to curse the French with appropriate gestures and to sing anti-French songs. She did also teach us to recite real French poetry and sing more conventional songs and to sew and make paper flowers.

Countess Plunkett liked only French to be spoken at the dinner table and the children did learn enough of the language to read French books of all kinds for pleasure. Food was supposed to be sent to Charleville from town on a regular basis, but their mother frequently forgot. Six children, a couple of servants and a wild governess in a country house with no access to money or shops needed to be resourceful. When they ran out of food there were hens but the hen-house was kept locked and the Countess kept the key with her in town so Moya was delegated to break in to it and take the eggs, which she did by squeezing through the hens’ door. It was in Charleville also that they got Black Bess, a well-trained, good-mannered four-year-old pony. The older children could ride her and drive her in the trap, enabling them to explore the countryside with great freedom.

Jack Plunkett, the youngest of the seven children, was born that October and shortly afterwards the rest of them were brought back to Fitzwilliam Street.

Count Plunkett’s title was bestowed on him by the Pope in recognition of his gift to an order of nuns, The Little Company of Mary (known as The Blue Nuns), of a villa in Rome so that the order could have a house there. He was a nationalist in the Parnellite tradition, having been a friend of both Isaac Butt and Charles Stewart Parnell himself. He stood for election as a Parnellite in constituencies where he was unlikely to win because he could afford to lose his deposit, but could test support and divide the opposition vote. He also undertook, at his own expense, to reform and update the St Stephen’s Green electoral register, which covered a large area o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Reviews

- Title Page

- DEDICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 16LIVES Timeline

- 16LIVESMAP

- 16LIVES - Series Introduction

- CONTENTS

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1: 1886–1902 The Young Plunketts

- CHAPTER 2: 1902–1906 Country Life

- CHAPTER 3: 1906–1908 Stonyhurst

- CHAPTER 4: 1908–1910 Many-Sided Puzzle

- CHAPTER 5: 1911 A Social Life

- CHAPTER 6: 1911–1912 Algiers

- CHAPTER 7: 1912 Algiers, Dublin, Limbo

- CHAPTER 8: January To July 1913 The Good Life And The Review

- CHAPTER 9: August To November 1913 The Lockout And The Peace Committee

- CHAPTER 10: November 1913-July 1914 A Long-Awaited Force

- CHAPTER 11: July to December 1914Words, Actions And War

- CHAPTER 12: January To April 1915 To Germany Through The War

- CHAPTER 13: May To October 1915 Decision And Command

- CHAPTER 14: October 1915-February 1916 Passion And Plans

- CHAPTER 15: 1916 Brinks Of Disintegration

- CHAPTER 16: 1916 Rising And Falling

- CHAPTER 17: 1916The Dark Way

- Appendix

- Endnotes

- Sources

- Index

- Plates

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Joseph Plunkett by Honor O Brolchain in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.