eBook - ePub

A Child's Brain

The Impact of Advanced Research on Cognitive and Social Behavior

This is a test

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Offers research on the development, organization, and operation of the child's brain. This volume outlines for educators the essence of the burgeoning fields of brain research specifically focusing on the child's brain. Exploring the ageless questions of how do we learn, acquire knowledge, process information and what is memory, and additionally what are the organisational, curricular and instructional implications for educators. This issue discusses the breakthroughs of computer science in understanding brain functions, research into the hemispheric processes of the brain and the emerging area of cognitive science, in relation to educators and the translation of recent brain research into practice.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Child's Brain by Mary Frank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IMPACT ON LEARNING BEHAVIORS

Cognitive Levels Matching: An Instructional Model and a Model of Teacher Change

Patricia Arlin, Department of Educational Psychology, The University of British Columbia, 2125 Main Mall, Vancouver, B. C. V6T 125, Canada.

ABSTRACT. Cognitive levels matching refers to a teacher’s ability to use formal and informal means of assessing the cognitive levels of students and to adapt instruction according to student needs. This ability is contingent upon the teacher acquiring a “developmental perspective.” The methods for acquiring this perspective suggest a fundamental change in the way the teacher thinks about instruction. The renewed emphasis on cognitive levels matching is the result of current interest in neurobiological research, particularly that of Epstein. Although cognitive levels matching (CLM) cannot directly test his hypotheses, the emphasis of CLM has become an emphasis on strategies to assist teachers to teach from a developmental point-of-view. Four informal strategies are described which can assist teachers to teach “from the child’s point-of-view and thus to begin the process of matching.”

COGNITIVE LEVEL MATCHING

In the early 1960s, J. McVicker Hunt described the major problem facing education as “the problem of the match” (1962). While the framework for cognitive levels matching has thus been in place for a number of years, what was required was the provision of techniques for acquiring a developmental perspective, the actual specification of educational needs in terms of stages or levels, and developmentally informed means of evaluating instructional materials in terms of intellectual ability and developmental readiness. Cognitive Levels Matching provides a means of fulfilling these requirements. It provides a framework for both curriculum development and a developmental curriculum. And the process becomes a model of teacher change.

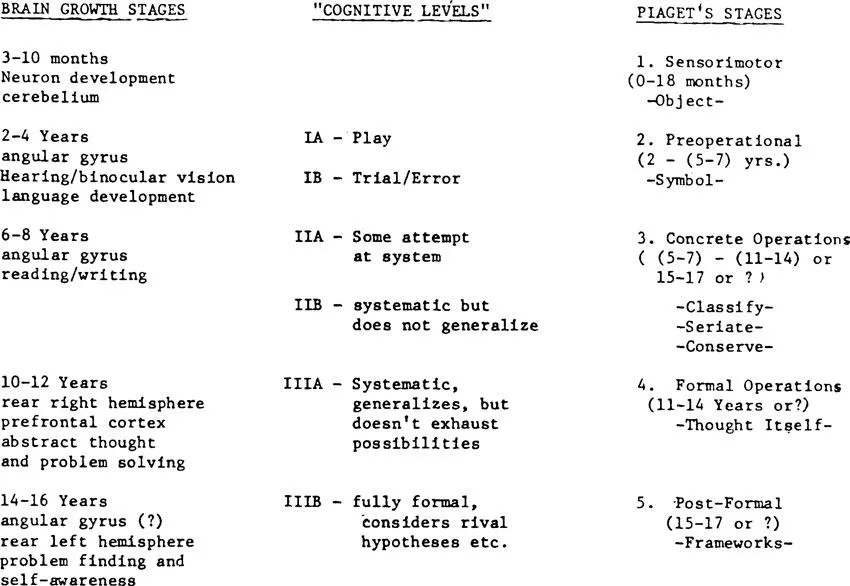

Cognitive levels are defined primarily in terms of Piaget’s four stages of development (Arlin, reference note 1; Brooks, Fusco, Grennon, 1983; Epstein, 1981). The term levels is used instead of stages because Inhelder and Piaget (1958) employ this term to describe the performance of children and adolescents on a variety of formal reasoning tasks; characterizing trial and error approaches of young children to the solution of problems as Level IA and the sophisticated use of various logic forms and concepts as Level IIIB.

Inhelder and Piaget’s description of six levels roughly approximates three of their stages in the development of logical thinking: preoperational, concrete operational thought and formal operational thought. Figure 1 is a summary of these stages with the major cognitive conquest of each stage as characterized by Elkind (1967). The broad outline of Piaget’s model is a familiar one but it is important to emphasize that each cognitive conquest associated with each stage represents a “new means” which becomes available to the child for actively building up knowledge of the world. For example is the baby’s own action on objects that is the basis for knowledge in the sensorimotor stage. The young child uses symbol or language as a way of learning about objects so that not only her actions but also her words, sounds, and actions are constructed about and between objects through language. Each of these new ways of constructing knowledge suggests strengths and limitations in child thought and reinforces the basic Piagetian notion that child thought really is different in kind than adult thought. The child’s point-of-view, the child’s construction of knowledge, is different than the teacher’s.

The current popularity of the concept of cognitive levels matching is due in large measure to the neurobiological research and speculations about the educational implications of that research by Epstein (1974a, 1974b, 1978, 1981). His brain growth periodicity proposals are offered as the neurobiological basis for stage transitions and change of level in cognitive development.

They are reinforced by the remarkable parallel between the ages of significant brain growth and the ages of potential onset of new cognitive stages as illustrated in the figure above. The original working hypothesis of the CLM projects was:

If neurobiological changes occur on a regular timetable that parallels that specified by Piaget for the onset of the stages of cognitive development then these neurobiological changes may bring about a structural change in the brain which may set up the possibility that a change in cognitive functioning may occur. The Piagetian model represents a first approximation of what those functional changes might entail. Particularly at the onset of the stage of formal operations. It is hypothesized that those functional changes will only occur in the presence of appropriate instructional intervention and experience and not outside these conditions.

While Epstein’s neurobiological research and his related educational hypotheses were the initial impetus for the CLM projects, it is clear that such projects cannot provide a direct test of these hypotheses. One assumption that the projects share with Epstein is that the optimal times for such interventions may well be at the ages of onset of the Piagetian stages.

Cognitive Level Matching: Cognitive Demands

The concept of cognitive levels matching involves a complimentary concept of “the cognitive demands” of tasks. It is essential to ask what particular type of logical thinking or concepts are necessary to develop a new concept and thus come to understand the curricular task. For example, the child is asked what is the meaning of the simile “My shadow is like a piece of the night.” The cognitive demand here requires ability to perform simple and multiple classifications. Mentally the child has to list the attributes of both shadows and night. Then the child has to search those lists to find out what shadows and nights have in common. This apparently simple task involves the child’s ability to classify, to list attributes of objects, and to compare these lists and classifications.

While the ability to classify may be a logical prerequisite or necessary “demand” for this comprehension task, it is not sufficient in and of itself to insure the child’s success. Children who lack the ability to classify, even if they can read the example, usually give literal answers. Typical answers include: “It means it is dark outside”; or “It’s night time” or “Someone is chasing you down the street” (Arlin, 1978; Cometa & Eson, 1978). These literal responses are examples of “mismatches.” The demands of the task are beyond the level of the students and so the students produce these answers.

Assessment

The Arlin Test of Formal Reasoning (1982) for cognitive levels involves the use of paper-and-pencil tests for concrete and formal reasoning (Arlin, 1982; Shayer, Adey & Wylan, 1981), and traditional clinical methods (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958, 1964). However, the emphasis in this article will be on the teacher’s gradual development of strategies to do informal assessments of cognitive levels as evidence of these levels occurs in their daily interactions with students. For more information on the Formal Reasoning Test that includes prerequisites, 30 substates characteristics and curriculum example tasks, contact Dr. Arlin (reference note 5).

INFORMAL ASSESSMENTS

There are four general strategies which are derived from Piagetian and Neo-Piagetian research which provide the framework for these informal assessments. As the teacher develops a working knowledge of these research traditions, the strategies become the bridge between theory and practice. Both the knowledge base and the strategies gradually assist the teacher to acquire a developmental perspective. The knowledge base is acquired through opportunities provided teachers to come into contact with “powerful ideas” (Goodlad, 1983).

COGNITIVE LEVEL MATCHING: A DEVELOPMENTAL PERSPECTIVE

A developmental perspective is a major component in the models of instruction (Arlin, reference note 1; Brooks, reference note 3). To have a developmental perspective is to consider curriculum and instruction in general, and the minute-by-minute interactions with children in particular from “the child’s point-of-view” (Elkind, 1976). It was in these terms that Elkind described the contribution of child development to classroom practice:

…one of the most important contributions child development can make is not so much particular contents, and principles of learning, as a general orientation towards children. What the developmentalist has to offer the teacher is first and foremost a developmental perspective, and techniques for exploring and revealing the child’s own view of reality (1976, p. 53).

Hunt and Sullivan (1974) made a similar point when they suggested that for a developmental theory to be of help to teachers it “should specify the educational need of students at different stages of development and should distinguish between a child’s immediate needs and his longterm requirements for growth” (p. 206).

The same sentiment appears in earlier writings of Ausubel:

…it is legitimate to evaluate the internal logic of instructional materials from the standpoint of their appropriateness for learners at a specific level of intellectual ability and of subject matter and developmental readiness (1968, p.29).

The strategies to be described below can be used at all levels of schooling. The initial focus and use of these strategies, however, was within middle schools. Students are typically eleven to fourteen years old in most middle school settings. Cognitive developmental researchers consistently report that approximately 50 percent of the adolescent and young adult population do not exhibit the use of formal operational thought when tested in the traditional clinical ways or in ways adapted by researchers (Keating, 1980; Maratono, 1977; Neimark, 1975, 1979).

It has often been suggested that the failure of adolescents to develop formal operational reasoning may be a function of the failure of educational institutions to provide appropriate impetus for such thought (Biggs & Collis, 1980; Kuhn, 1979). Despite this proposal, little systematic attempt has been made in public schools to adopt a developmental psychology of education and to structure school experiences to facilitate cognitive developmental change. The use of the following four strategies may be a first step toward the construction of an appropriate developmental curriculum that includes a developmental perspective.

Four General Strategies

The four general strategies are: (1) the identification of the child’s “point-of-view”; (2) the analysis of children’s responses in terms of the questions the children ask themselves; (3) the identification of specific Piagetian schemes, operations and concepts which comprise the “cognitive demands” of various Piagetian tasks; and (4) the analysis of children’s faulty procedures or strategies. These general strategies are the first step in assisting teachers to reflect on the teaching act from a developmental perspective. They set up the possibility that out of that reflection might come action, adaptation of instruction and change.

First Strategy

The identification of the child’s “point-of-view.” It is by observing children, listening to children, and asking questions of children that opportunities are presented to observe tasks, experiences and concepts from their point-of-view. The emphasis of CLM on teachers acquiring a developmental perspective is focused directly on the teachers’ coming in contact with the child’s point-of-view. Unless tasks, concepts, one’s own teaching are seen from this perspective, matching is an unattainable goal. Teachers, in planning lessons, attempt to anticipate children’s responses, questions and difficulties with the lesson. Still, many lessons result in the unexpected. Children respond often in ways remarkably different from what adults expect. Piaget’s clinical method takes this difference into account, expects it and uses it as a guide to children’s thinking. Teachers use this method practically when they reflect on the child’s point of view in their daily interactions. Three examples are drawn from three different age groups to illustrate this practical application of the clinical method.

An item on a Province-wide mathematics achievement test (Robitaille & Sherrill, 1977) taken by fourth graders at the beginning of the school year serves as our first example. The children were asked the question “Which group of dots is ½ shaded?” Approximately 60 percent of the children chose the correct answer where three dots were shaded and three were not. What was particularly interesting though was that the next most popular answer was the group of dots with two dots shaded and one dot unshaded. One possible explanation for the children’s choice is that they related part-to-part rather than part to whole. They selected an answer of one and two rather than one-out-of-two. It is not uncommon in the Piagetian literature to report that approximately 40 percent of children age nine years are unable to coordinate part-whole relationships as represented in class inclusion problems and as possibly implied in this example.

The second example is taken from a seventh grade research study of children’s comprehension of metaphors (Arlin, 1978). The young person is asked what is meant by the line “Tiptoe night comes down the lane, all alone, without a word, taking for his own again every little flower and bird.” The stud...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Brain Structure

- Impact on Learning Behaviors

- Future Issues

- Selected Readings