![]()

One

Universals and Particulars: Themes and Persons

EMPIRES LIVE on in memory and history more than other states. The Inca empire that extended along the central Andes of South America has remained present not just to historians but to the people of Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and especially those of Peru for nearly half a millennium after its fall. Why and how the Incas fell prey to the Spanish, and what the consequences were, has been a subject of reflection ever since it happened. In the early seventeenth century, an Andean lord wrote a historical meditation on this topic, short in length but weighty in content. At the center of this work lies the transformantion of Inca into Spanish Peru. The book begins with the earliest human beings in the Andes, goes on to the Inca empire, and continues to the coming of the Spanish in 1532 and the Christianization of the peoples over whom the Incas had ruled, down to the author’s own day. The author’s long name, consisting of Christian, Spanish, and Andean components, reflects the book’s content. He was called Don Joan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua.1 Joan preceded by the title “don” indicating noble birth was his baptismal name, to which he added the Christian epithet “of the Holy Cross.” Yamqui was an Inca royal title, and Pachacuti, meaning “upheaval” or “end of the world,” was the name given to the ruler who had initiated Inca imperial expansion on a grand scale, over two centuries before Don Joan wrote his book.2 Finally, Salcamaygua is a “red flower of the highlands.”3

Don Joan and his forebears came from Guaygua, a couple of days’ journey south of the old Inca capital of Cuzco, in the central highlands of the Andes—the region designated poetically by the “red flower.” Part of the history that Don Joan recorded in his book was about the incorporation of this region into the Inca empire in the time of the Inca Pachacuti.4 From childhood, Don Joan had heard about the “ancient records, histories, customs and legends” of his homeland, and when he had reached adulthood, people were still “constantly talking about them.”5 But just the memory on its own was not sufficient if the events, especially those of the years after the Spanish had come, could not also be explained. Given the cataclysmic nature of what had happened—a change not just of governance, but of language, culture, and religion, not to mention the deaths of countless people—much explanation was called for.

Don Joan was proud to be a Christian, glad to live with the “holy benediction” of the church and “free of the servitude” of the ancient Andean deities. As he looked back over the history of the Incas, and to the times before the Incas, it seemed that traces and tokens of the true Christian religion had been present in the Andes for a very long time. Like several of his contemporaries, Don Joan thought that one of the apostles had reached the Andes and had made a beginning of teaching this true religion.6 So it was that the Incas themselves had worshipped the one and only god and battled against false gods, perceiving in the festivals that they celebrated for the Maker of the world an “image of the true festival” that was to come in eternity.7 And yet, so Don Joan believed, the Incas were also aware that something was as yet missing, without being able to comprehend exactly what it was.

Take the Inca Pachacuti. In his old age, he heard that a ship had come to the Andes “from the other world” and a year later a young man appeared in the main square of Cuzco with a large book. But the Inca paid no attention to the boy and gave the book to an attendant. Whereupon the boy took the book away from the attendant, disappeared round a corner, and was gone. In vain did Pachacuti Inca order that the boy be looked for. No one ever learned who he was, and the aged Inca undertook a six-month fast “without knowing.”8 Some decades later another enigmatic event occurred. A messenger cloaked in black arrived before Pachacuti’s grandson, the Inca Guayna Capac, and gave him a locked box which—so the Maker of the world had instructed—only the Inca was to open. When Guayna Capac did open the box, something like butterflies or little pieces of paper fluttered out of it, scattered, and disappeared. This was the plague of measles that preceded the coming of the Spanish and that killed so many Andean people. Before long, the Inca himself died of it.9

Don Joan wrote in a mixture of Spanish and his native Quechua. His style and outlook reflect that of missionary sermons and Christian teaching.10 Did he perhaps also know the story of the Sibyl and King Tarquin of Rome? The Sibyl had appeared before the king, offering for sale nine books containing the “destinies and remedies” of Rome for 300 gold coins. When the king refused to buy the books, the Sibyl burned three of them, still asking the same price, and when he refused again, she burned another three. Whereupon the king purchased the remainder for the price originally stipulated and the Sibyl disappeared.11 And did Don Joan know the Greek myth about Pandora’s box that was opened unknowingly and contained the ills that ever thereafter befell humankind?12 If he did, this myth would have conveyed an independent Andean meaning to him. For pputi, the Quechua term for box that Don Joan used, is semantically linked to a cluster of terms denoting sadness and affliction.13 At any rate, in both these pairs of stories the explanatory drifts of the Andean and the European versions are closely intertwined.

A century after the arrival of the Spanish, Don Joan like other Andean nobles of his time portrayed his ancestors as having welcomed these newcomers, bearers as he described them of the Christian message. On their side, so Don Joan thought, Andean people were ready for the Gospel, willing and able to worship the true god and to pray to him in their own native Quechua.14 But the presence of the Spanish in the Andes brought with it a host of evil consequences that it was rarely possible to discuss other than indirectly and allusively. Rome’s King Tarquin was left with three of the Sibyl’s nine books, but Pachacuti Inca was left “not knowing.” Yet worse, the gift of the box to Inca Guayna Capac, in which somehow the Maker of all things was involved, turned out to be a purposefully murderous gift of which the Inca had been forewarned but that he could not avert. Before the box arrived, Guayna Capac saw a midnight vision: he felt himself to be surrounded by “millions and millions of people” who were “the souls of the living whom God was showing him, indicating that they all had to die in the pestilence.” These souls, so the Inca understood, “were coming against” him and “were his enemies.”15 Don Joan resorted to the stories about the book and the box of afflictions, charged as they already were with ancient and multiple meanings, to express the fundamental contradiction that pervaded the lives of so many people: on the one hand, the undeniable evil of subjection to alien rulers, and on the other the—to him—equally undeniable good of being gathered into the community of “our holy faith.” In the process of being retold, these ancient stories acquired new dimensions, and they served as a communicative bridge of sorts between Andean people and Spanish newcomers, all of whom Don Joan addressed in his book of historical meditations.16

The Spanish, even those who read rarely or not at all, could be expected to understand such a communication because they were all steeped not just in Christianity but also in remnants of the Greek and especially the Roman past. Many would have heard the Sibyl chant her prophecies about the coming of Christ during the celebration of his Nativity according to the old pre–Tridentine Spanish liturgy.17 From late antiquity onward, through the long sequence of cultural and political upheavals that transformed Roman into early modern Spain, the Greek and Roman past lived on in the present by virtue of ordinary continuities of daily life. The layout of some cities, the design of private and public buildings, the shape and decoration of tools and utensils, the titles and functions of dignitaries, and the content of law all bore traces of Roman and post–Roman antiquity.18 Throughout the Iberian Peninsula, people were walking and riding along the old Roman roads, passing Roman ruins and whatever Roman monuments had withstood the ravages of time. Not infrequently, the traveler would pass a Roman distance marker, and some of these dated back to the time of Christ.19 The figures of classical myth and history continued to occupy poets, storytellers, and artists to such an extent that many of them became familiar friends, speaking from the pages of books, looking out at from tapestries, paintings, and sculptures, and singing in songs both sacred and secular. Planets named after the ancient gods—Venus, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, and Saturn, along with Sun and Moon were imbued with a divine and personalized energy. They circled the sky and extended their influence over humans and their environment.20 Finally, the political forms, monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, that had engaged the thoughts of Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero lived on in the writings of jurists, in legal practice, and in the governance of cities and kingdoms.21

It was not long before this manifold legacy was felt in the Americas as well. Legal and administrative practices that were taken for granted in the Peninsula were imposed on indigenous peoples without further ado and soon became ubiquitous.22 In the Andes as elsewhere, the lay

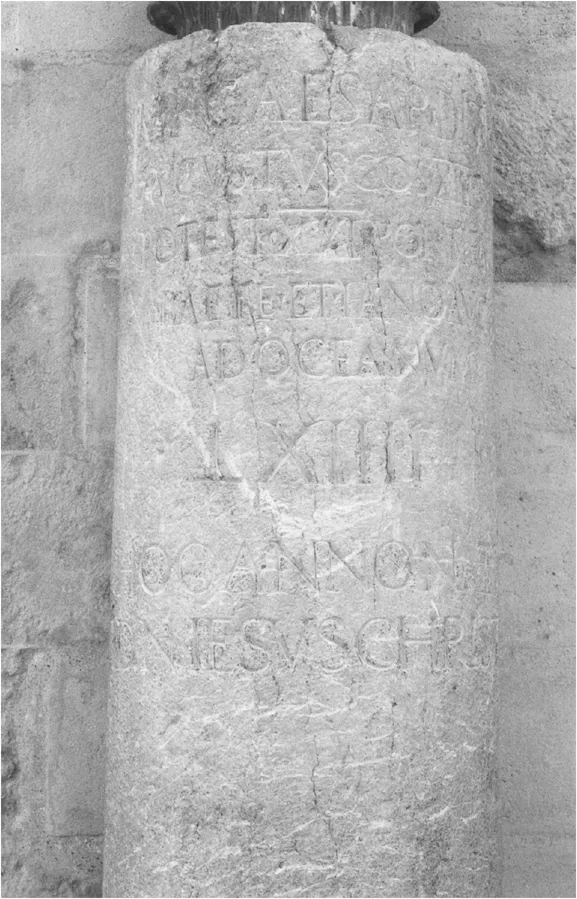

1. In the lifetime of the historian Ambrosio Morales, this Roman milestone, measuring the distance from Córdoba to the ocean, was to be found next to the entrance of the Mezquita that had been converted into the Cathedral of Córdoba, where it still is. Morales thought that the date given on the milestone, that is, the thirteenth consulship of Augustus, and the twenty-first year of his tenure of the tribunician power, corresponded to the year of Christ’s nativity. This information was accordingly added in Latin below the Roman inscription.

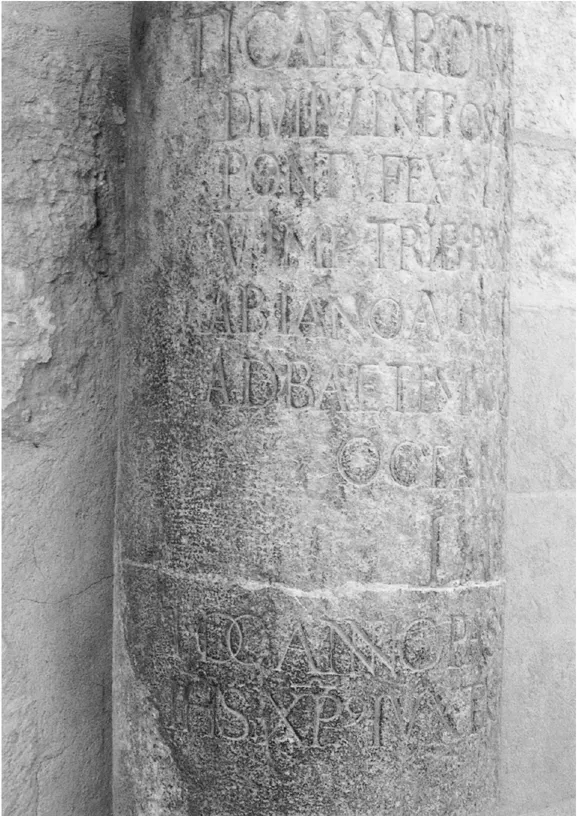

2. This Roman milestone, which was also placed next to the entrance of the Cathedral of Córdoba, where Morales saw it, names the emperor Tiberius and likewise measures the distance from Córdoba to the ocean. According to the historian’s reckoning, its date was the year before the crucifixion of Christ. Someone else, however, thought the date was the very year of the crucifixion, and Latin words to that effect were carved below the Roman inscription.

out of the cities the Spanish founded, the buildings that indigenous masons and artisans erected in them, the stories the Spanish told, and even the fabric of Christian teaching all bore a stamp of the Greek and most of all the Roman past.23 Representations of Roman deities decorated Andean churches, mythic and historical figures of the Greek and Roman past paraded through the streets during festivals, Latin and sometimes Greek were taught in universities. Public rituals, the arrivals and departures of viceroys and other dignitaries, the accession and funerary ceremonies of the kings of Spain as celebrated in Lima and other Peruvian cities were deeply imbued with Roman gestures and political concepts.24

In short, the classical past in the Andes was a dynamic and far from uniform force that changed over time, as it had done in Spain also. In one sense, throughout the Middle Ages, the figures of classical antiquity were simply absorbed into the fabric of the present. As a result, scholars and historians in fifteenth-century Spain were able to think about knightly honor and military discipline, lived and practiced in their own day, as continuous with, and even as identical to, Roman precedent. Equally, Cicero’s precepts about political friendship as...