![]()

ONE | THE IMBRICATED STRUCTURES

OF REFUGEEHOOD |

DISPLACEMENTS

It is summer 2003, a little after Turkish-Cypriot authorities announced they would no longer prevent people from crossing in and out of a self-declared state in northern Cyprus, across the island’s Green Line boundary. Masses have been flocking to checkpoints since that late April declaration, venturing into places they had not visited since the bloody period of the 1960s and the war of 1974. A restaurant in the old commercial center of northern Nicosia is preparing for the evening’s clientele. As we sit down, a friend joins our table for drinks. There is excitement over the opening of the border. We reminisce at how the last time we met some months ago we had to drive for an hour to meet outside Pyla village, in the east of the island, the only location reachable from both sides and closely watched. We keep repeating to ourselves and each other, through a myriad of examples, how just a couple of months ago, what we are doing tonight was unimaginable.

There is a mood of playfulness even as we criticize societal structures that endure. There is still need for change, we agree, and walls of prejudice to be broken. The South Asian waiter serving us, we assume, is exemplary of the problems of discrimination and integration still existing. So we ask about his living conditions and, not surprisingly, hear they are not great. But he also expresses a different concern, since after his visa had expired, he crossed from the south to escape arrest and continue making a living in the north: “Every day I wake up and look across to the other side and remember the house where I used to live, and the place where I worked. It’s so near and yet I can’t go.”

These words prompted a long reflexive pause that inspired the writing of this book. At that moment in 2003, those words sounded strangely familiar; and as I continued to reflect on their possible meanings, I became aware of how deeply imbricated “the Cyprus problem” is with the experience of being in Cyprus—no matter where one is placed and what position one occupies. This book is the outcome of those reflections and the ten years of research that they have informed. It is a study that looks at all those minor losses that have been engulfed by the Cyprus problem for the last half-century and treated as insignificant, or at least secondary, to that other big question and the questions that attend it: how the Cyprus problem came to be, how the two sides interpret things, what the political future might hold, how we (academics, activists, citizens, internationals, mediators) can help realize that future. Those were the questions that occupied many of us in that jubilant mood of 2003 when this comment of tangential loss brought home to me the expanse of all those questions that major losses foreclose. Those minor losses, I came to realize, have not been incidental to the conflict—they have been shaped by it, and they have shaped subjectivities within and beyond it. And just like in other long-lasting conflict situations (Ireland, the Basque and Catalan regions of Spain, Israel/Palestine), those subjectivities are now informing everyday “normal” relations. They service the jubilant and other affective socialities forming around newfound postconflict freedoms—as these develop across the now loosely monitored border and take the form of movement, work, and consumption. It is to these processes that we must now attend if we are to understand the afterlife of conflict.

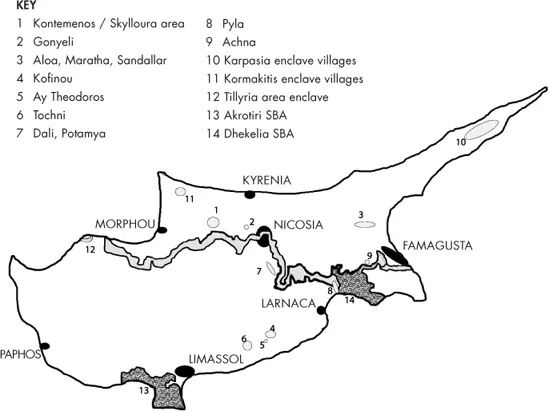

Physical separation in Cyprus today is no longer a vitally urgent concern for many locals, even though political division is the cornerstone of official rhetoric (see figure 1.1). But the echo of the waiter’s words, which communicate this vital urgency in a surprisingly slanted way, continues to inform my understanding of the border in Cyprus. Those words were strangely familiar in multiple senses. On the one hand, they condensed the hegemonic Greek-Cypriot discourse of displacement in Cyprus: that “our” lands, having been snatched unjustly by Turkey after its invasion in 1974, are just over there, so near and yet so far, waiting for us to liberate them. The motif of the Greek-Cypriot refugee seeing her house but not being able to touch it appears in all kinds of literature from elementary-school books, where short stories depict children sending kites across the Green Line, to poems, fiction, and film, which show envy of stray animals crossing—something people cannot do. Before the opening of the central crossing point in Nicosia, binoculars were handed to tourists by Greek-Cypriot soldiers on guard, so they could see across the other side; dignitaries are still often bussed to the easternmost border point in the village of Deryneia to peer through a viewing machine turned towards the abandoned beach resort of Varosha, outside the Turkish-military-controlled town of Famagusta (see figure 1.2). There is a dwelling on division that has come to define Greek-Cypriot subjectivity. The tragedy of Greek-Cypriot refugees, the rhetoric goes, is that they are “refugees in their own country.” The impossibility of crossing the border “to go home” was for many years packaged as a corporeal experience for foreigners who, having felt it, are encouraged to become ambassadors for the cause of return. For the Greek-Cypriot-schooled public, the effect was to cultivate a sense of generalized refugeehood. This is a notion I explore in later chapters. To Greek-Cypriots growing up after 1974, the definition of “refugee” seemed obvious and the sentiments of loss that were expected to attend it were perceived as a structure of feeling that the whole population should share. The affective register was, and largely remains, central to the governmentality of conflict subjectivities.

FIGURE 1.1.Map of Cyprus, showing areas mentioned in the book.

FIGURE 1.2.Deryneia viewpoint: Entrance sign (top); coin-operated viewingmachine (center); Varosha ruins outside Famagusta town through the view finder (bottom).

So to hear this discourse articulated on the opposite side of the divide seemed strange—it was not quite refugeehood. First, the unreachable other side was now the south, not the north. This was only partly strange. Since 1963, Turkish-Cypriots have often articulated longing for homes left in the south, and this has been well researched. This longing is well known, and it is also opposed to the official rhetoric that, since the war of 1974, has emphasized forgetting the homes in the south and looking forward to a brighter future in new homes in the north. Even when not explicitly opposed to official discourse, articulations of longing are positioned against this background, making the desire for return and lament for lost homes complexly ambivalent. What seemed strange, in this sense, was a kind of geographic dislocation of affect. It is not that people in northern Cyprus don’t pine for homes in the south, but that they pine for them in this way.

Second, the time of this affective expression seemed strange. The inability to go home, which produced this longing, was not in response to the solidity of the border. It took shape precisely at the moment the border opened up, and when it seemed that in fact it was about to be dissolved altogether. Turkish-Cypriot authorities decided to allow crossings over the Green Line in April 2003, during a period (2002–2004) of intense political negotiations. At the end of these, a plan for reunification (the Annan Plan) was put to a referendum in April 2004 and rejected by Greek-Cypriots, while Turkish-Cypriots supported it. This deferred the dissolution of the border; but this referendum was still to come in that summer evening of 2003, and the atmosphere of excitement was not conducive to such predictions, as I explain in later chapters. The waiter’s comment exemplified what much of border-studies literature has recently been documenting: that changes in the operations of bordering (the materialities of borders, the apparatus that govern them, and the practices that develop around them) are not evenly distributed across populations. Instead, the easing of some movement might imply, or in this case accentuate, the restriction of other movements (Aas 2011; Rygiel 2010; Brown 2010; Bigo 2006).

The radical change in the operation of the border in Cyprus in 2003 saw thousands streaming across it. Going home was one of the primary activities Greek-Cypriots with ties to the north had been engaging in, en masse, and on a daily basis throughout the previous months. Middle-aged men and women visited homes they remembered from childhood; elderly parents were driven to meet neighbors and friends, collect agricultural produce from fields, and retrieve movables saved and collected by those now living in their former homes; youngsters were guided through houses that suddenly seemed much smaller and through landscapes less grand than they had remembered or imagined. There was ambivalence here too in the encounters between different owners and in the performance of return. But there was a definite sense that the main barrier to whatever return might ensue, was slowly being lifted. So on that evening, the emblematic articulation of Greek-Cypriot refugeehood seemed misplaced, in both place and time. This was not the time to pine for lost homes, but to celebrate their imminent recovery—for Cypriots.

And ultimately, the cause of that misplacement was the strangeness of a specific subjectivity. It seemed strange to hear what I had come to recognize as a Greek-Cypriot discourse on loss, articulated by a stranger—an immigrant with no apparent familial ties to Cyprus. There was an uncomfortable realization of the presumptuousness with which I, and others, had approached the Cyprus conflict up to then, which guided much of my questioning since. So what did its strangeness mean? Is the so-near-yet-so-far discourse actually the articulation of something banally self-evident, perhaps, and not the epitome of Greek-Cypriot politics at all? And does this banality point to something universally applicable rather than a feature of a specific political culture? What is the affect that a sealed border exudes and how does it come to surpass the conflict that sealed it in the first place? How do ethnic divides exceed the binaries that define them? At the time, the waiter’s comment seemed a spontaneous attempt to relate the excitement of meeting someone coming from the side that had become inaccessible. I since wondered whether it might have also been mediated by the experience of having lived in the south and among the Greek-Cypriot refugee discourse (likely to have been expressed by people above him in the class hierarchy). But it is the questions about the excesses of conflict imaginaries and the losses they foreclose that I have repeatedly returned to, and which I want to highlight as inroads to reconsidering the subjectivity of refugeehood in general.

To recognize that the waiter’s discourse is misplaced is to recognize the misplacement of subjectivity too. And to reflect theoretically on the validity of these analytics of misplacement requires that we ask where it is that subjectivity is “correctly” placed in Cyprus. Who are Cypriots, and who are the proper subjects of Cypriot refugeehood? To probe this question requires examination of several layers of discourses about refugeehood, displacement, and loss, which I engage in later on. And most importantly, I argue, it requires engagement with the ways in which all these layers are connected to each other—examined under the metaphor of imbrication.

Such imbrication is not unique to Cyprus. To return to the long-standing conflicts previously mentioned, the discursive structures developed in Palestine, Ireland, and Spain govern and affect the experience and policy of migration today. After the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland, where a border has undergone a similarly radical shift as in Cyprus, the legacy of the conflict has created an all too familiar “grim reality for people of colour, refugees, and migrants” (McVeigh and Rolston 2007, 11) where the “politics of identification … position migrants and minority ethnic communities within dominant sectarian discourse” (Geoghegan 2008, 174). In Ireland, narratives of immigration and the legitimacy of refugees entail “unresolved Irish memories of colonisation, the Famine, and emigration” (Moriarty 2005, 6.7). The politics of occupation and international recognition in which the Israeli/Palestinian conflict is embedded is also familiar to Cyprus. International migration in Palestine arises through these politics as a question on which “Israel demands the last word,” and this results in limited and patchy regulation by the Palestinian Authority, as exemplified by failure to link regular work with regular stay (Khalil 2008, 12). And on the other side of the wall, “Israel’s labor migration policy reflects the state’s continuous anxiety over a changing ethnoscape” (Raijman, Schammah-Gesser, and Kemp 2003, 733), an anxiety stemming directly from the history of the conflict there, and resulting in the placement of irregular women migrants at the bottom of the scale. This arises because the citizenship regime, ethnically determined through and through, leaves no prospects of integration, assigns foreign workers to a category “with a biblical connotation of profanity” (ibid., 747) and conceptualizes domestic work within the patriarchal-military imaginary that societies emerging from conflict, like Israel and Cyprus, know so well. And in Spain, conflicts over autonomy and secession in the Basque region and Catalonia have differentiated both areas in their immigration policies. Catalonian parties have articulated opposition to centralizing attempts from Madrid on the point of immigration policy resulting in sometimes more progressive and at other times more restrictive approaches. In the referendum of 2017, which solicited independence from Madrid, both pro- and anti-immigration arguments propped the separatist position: independence could ensure more autonomy to improve integration structures, and more autonomy to stem migration policies too. The strong emphasis on Catalan identity and language, which is currently a cornerstone of integration policies, can easily be adapted to opposing perspectives that drive the secessionist argument. In the Basque region, on the other hand, Basque parties have built on “the link between the promotion of internal diversity and Basque values” (Jeram 2013). The legacy of conflict in Spain means, in short, that “immigration is not so much a component of diversity as it is a vehicle through which existing diversities are brought to the fore” (Zapata-Barerro 2010, 171). These complex situations are in different ways reflected in the themes I examine in Cyprus.

A major claim of this book is that the entrenchment of conflict structures in society and government implicates—and most importantly imbricates—forms of classification and exclusion, as well as the experiences that go with them, that stretch far beyond the conflict. And it is out of these imbrications that postconflict subjects of multiple positionings emerge. In Cyprus, the framing of such imbrications is refugeehood.

REFUGEEHOOD, POWER, AND CONFLICT

Wisdom has it that refugees flee war. Much less is said about what they find after they do so, not in terms of the reception they receive, but in terms of the conflicted societies they land in. At the same time, much of the literature on forced displacement grapples with this seemingly simple link between conflict and refugeehood. One example is the debate that persists over the appropriateness of the term “environmental refugees” to describe people who are forced out of unlivable habitats. And while environmental degradation could have been tied to wars and conflict in the past (El-Hinnawi 1985; Kibreab 1997), it now more often results from natural disasters and rising sea levels (Bates 2002; Keane 2003; Hartmann 2010). This only confirms a basic tenet of refugee studies: that refugeehood is not an objective but a political category. As McNamara puts it, “[The assertion] that environmental refugees do not exist is still a social construction of environmental refugees, a subject identity reliant on an absence or negation of a particular characteristic or condition” (2007, 15).

In the same way, the assertion that political and economic adversities can be separated out as producing refugees in the first instance and economic migrants in the second is also a social construction of refugees and economic migrants. This second debate, the most enduring in the field of forced migration studies, manifests the predicament of using legal standards to square politics and ethics. Many scholars have insisted for some time now on the need for policy makers to extend the interpretation of “refugee” from the two categories (political refugees/economic migrants) to account for the fact that most irregular migrants fall somewhere in the vast gray area between them. Scholars have convincingly argued that the insistence of states on this erroneously sharp distinction is a political tool that enables them to deny refugee protection to great numbers of people who might otherwise qualify for it (Gibney 2004). They have also shown that the legal basis of labeling refugees is a shifting field itself: over the last two decades, argues Zetter,

the refugee label has become politicized, on the one hand, by the process of bureaucratic fractioning which reproduces itself in populist and largely pejorative labels whilst, on the other, by legitimizing and presenting a wider political discourse of resistance to refugees and migrants as merely an apolitical set of bureaucratic categories. (2007, 174)

At the heart of this regime, Andersson has more recently argued (2014), is a vast industry that relies on security and surveillance apparatus and employs humanitarianism and development discourses to meet out profits on everyone but irregular migrants. And even though Andersson brackets out the legal debate and the terminology of “refugeehood” from his study, he makes it clear that this is the performative stake in the entire operation of what he instead terms the “illegality industry.” This use and abuse of the legal concept (Schuster 2003) also elicits differentiated practices of migration, we now know—far from being docile victims, asylum seekers make choices, often based on considerations of these shifting legal apparatus (Schuster 2005). But for precisely these reasons, others have argued, it is vital to insist on maintaining refugee status as a special category requiring protection irrespective of political priorities (Hathaway 2007). The discussion over the categories “refugee” and “internally displaced person” (henceforth IDP), developed on the back of two opposing perspectives on refugee assistance, is particularly interesting in this respect.

Described by Brun (2010) as the “UN-Brookings” and “ICRC” approaches, one focused on the tailoring of specialized assistance, the other on prioritizing needs. Like the categories previously discussed, both of these are also political. Brun shows how in Sri Lanka IDPs are provided humanitarian assistance and initial hospitality, but never fully integrated into the societies they flee too. The question is therefore both moral and political: it concerns the “responsibilities of institutions in dealing with internal displa...