![]()

1

Ojibwe Ethnogenesis and the Fur Trade

When about to depart to return home, presents of a steel axe, knife, beads, and a small strip of scarlet cloth were given him, which carefully depositing in his medicine bag, as sacred articles, he brought safely home to his people at La Pointe.

Lake Superior is the world’s largest freshwater lake, and it is the defining natural feature for the indigenous groups in the region. The Wisconsin Ojibwe people live throughout the Lake Superior lowland and Northern Highland provinces adjacent to and south of the Highland. Though once mountainous, the Northern Highland province is now a peneplain of upland plains and ridges. One type of ridge is the monadnocks that crest above the level of the peneplain. The most prominent monadnock in the state is Rib Mountain rising 640 feet above the level of most of the land in the region. The Penokee Range is also a monadnock. It is eighty miles long and about half a mile to a mile wide, located ten to fifteen miles from the southern shore of Lake Superior. “Old Baldy,” also known as “St. Peters Dome,” is on the eastern end of the Penokees. It is a red granite formation that rises to an elevation of 1565 feet and is a long-standing prayer site used by Bad River Ojibwe people and others over the centuries.

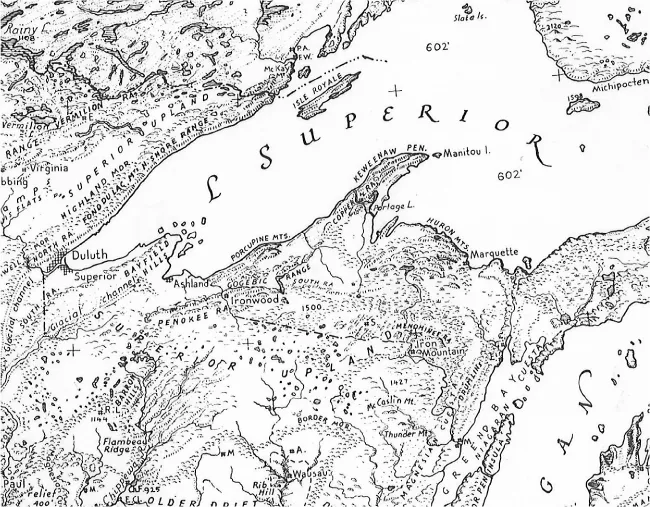

The Northern Highland abounds in lakes and swamps, and few areas of the world have more lakes to the square mile. Numerous rivers flow north into Lake Superior and just as many form the headwaters of the St. Croix, Chippewa, Upper Wisconsin, and Menominee Rivers, which flow into the Mississippi. Climate is seasonal, and the precipitation is moderate. This northern landscape shaped by the glaciers that left a “highly diverse set of landforms of moraines, outwash plains, drumlins, eskers, and glacial lake basins” is defined by the abundance of water manifested as rivers, streams, bogs, and lakes. See the map on the next page.

The Northern Highland, with its generally infertile thin and acidic soils, is a mixed forest of fifty to sixty tree species including deciduous trees such as maple, hemlock, beech, yellow birch, and evergreens such as pines, spruce, and fir. It is also abundant in blueberries, lingonberries, raspberries, juneberries, wild plums, cranberries, and wild strawberries. According to Nicholas Perrot, trader, interpreter, and government agent, beaver were very plentiful in northern Wisconsin in the mid-seventeenth century. In the late seventeenth century, according to British traders, “the Chippewa country south of Lake Superior was scarcely to be surpassed or equaled for its fine furs.” Indeed, John Pastor, author of What Should a Clever Moose Eat? Natural History, Ecology and the North Woods, asserted that the population density and quality of beaver fur was highest from the Great Lakes northward, and no other species in the region has played a larger role in shaping the land and waterscape.

Map 1.1. Detail of “Landforms of the United States” show the region. Erwin Raisz, Fifth edition, 1957. Courtesy of Raisz Landform Maps.

And it was a watery world. A number of navigable streams flow into Lake Superior draining the Northern Highland, which, in turn is honeycombed with navigable streams ultimately connected to the larger rivers and finally the Mississippi. Douglas Birk described the “surface water system” of the Ojibwe in this region as “labyrinthine” thereby “living in scattered enclaves.” Though there were nearly always a number of portages, people tended to think in terms of time spent in birchbark canoes when they thought about distance. The names of the communities also reflected this orientation, with most of the Ojibwe groups in the region calling themselves and being called after bodies of water: Lac du Flambeau, Lac Courte Oreilles, Bad River, Fond du Lac, Mole Lake, St. Croix, Leech Lake, Red Lake, Sandy Lake.

Anishinaabewaki, or Great Lakes Indian Country

In commenting on her magisterial Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History, Helen Tanner once confided that though Indian settlements carried identifying tribal names, there are no single-ethnicity villages in the region. All villages designated by a tribal name had members of other communities within them, usually affines but also war captives. These ethnonyms that we use so casually and confidently—Ojibwe, Menominee, Sauk, Fox—are generalizations, arguments, representations, claims about social boundedness and homogeneity made by interested parties both within and without in the guise of authoritative and definitive descriptions. The same point was made in the linguistic register in 1847 by Reverend Frederick Baraga, who worked among Ojibwe people. Responding to the commissioner of Indian affairs’ “Inquiries respecting the History, present Condition and future Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States” and asked about their dialects and languages, Baraga wrote in response: “This tribe speaks only Chippewa language, which is almost the same as the Ottawa, the algonquin, the potawatomi and the menomini languages. All these languages are only different dialects of the same language.”

Members of all of these groups could respond to a question about their identity with the autonym “Anishinaabe,” that is, “people,” or “real human being,” connoting “us” to their interlocutor and distinguishing themselves from people who spoke incomprehensibly. In Islands of History, Marshall Sahlins wrote that “there is no such thing as an immaculate perception,” a clever riff on the oft-made point about the social and cultural constitution of reality organized by unreflected-upon categories. I would add the corollary that there is no such thing as an uninterested representation, especially when constituting “us” and “them.” Identity is always situational and relational, even when—or especially when—the person asserting or representing an identity is claiming that it is not contextual.

In the spirit of this cautionary remark, “Chippewa” and “Ojibwe” are versions of each other and are both used by Anishinaabeg people when speaking English. “Ojibwe” has become more commonly used over the last several decades, so I default to that much of the time but also use “Anishinaabe” for the people and “Anishinaabeg” as adjective. In that “Chippewa” is often the legal designation of bands in Wisconsin, I will use that especially when the term has been used in a document under discussion.

I will default to “mixed blood” as shorthand for people with both indigenous and settler parentage rather than “Métis,” which I regard as anachronistic in this context. “Mixed-blood” is also used in the treaty provision that we are most interested in exploring. I recognize that the term smuggles in a racial ideology but not as crudely as “half-breeds,” though this is a term used by some mid-nineteenth-century indigenous people of mixed parentage as well. I will use it, marked in quotes, when discussing people who use this term for themselves in the immediate context of discussing a document in which the term occurs.

In the hierarchy of registers of discerning similarity and difference, inclusion and exclusion, the manner in which a person spoke was at the top of the list, as it still is today. Putative linguistic homogeneity is relative and obscures diversity. With variation at the level of the village, even the Algonquian, let alone the “Sauk,” or “Ottawa” or “Potawatomie” or “Ojibwe” were only relatively homogenous linguistic communities. Even today, in the first decades of the twenty-first century, after nearly a century of these languages being used chiefly for ceremonies in most these communities, speakers will say that the dialect of their community differs from that of the next community several score miles away. People related to each other in different ways navigated a rich soundscape that mapped onto a land and waterscape.

Then, of course, there is and was kinship as the hegemonic and very capacious mode of claiming and constituting similarity and difference. There were several categories of kin relations that all had similar physical substance. There were also other categories of relations that were different enough to marry. How one sounded on the topic of whom one and one’s interlocutor were related, that is, kinship, established the basis of the relationship they would have with each other. Michael Witgen makes much of this point in using the metaphor of shape-shifters in describing indigenous polities to capture their inherent “mobility and social flexibility,” the result of being organized by kinship. The result is “a dizzying number of amorphous and mobile social bodies.” There will be more to say about the exact nature of that kinship system in the next chapter, especially in regard to the shape of the kin group into which outsiders could be integrated.

Charles Callendar characterizes the Ottawa and Chippewa sociopolitical organization as small concentrations of several families at fishing sites and trading sites in the summer who then dispersed. He added that although patrilineal clans were present, their “corporate functions and features were at best very weak. Political organization was generally of the band type, with sporadic tendencies toward wider integration.” Theresa Schenck amends Callendar’s characterization of the centrality of clans and bands in her etymology of the now famous analytical term “totem,” reminding us that the term originates with the Algonquian word “oten,” meaning village. “[N]ind oten or nind odem … was soon heard as totem or dodem” and referred to “a group of people tied together by bonds of kinship, and who moved together seasonally.” And I would note here that kinship is bigger than patriliny, descent figured through men, or the strength of this ideology and practice among the Ojibwe in the earliest contact period being a matter of debate.

Heidi Bohaker characterizes Algonquian society generally and Ojibwe society in particular as essentially organized by nindoodemag, the first-person form of the name for a patrilineally inherited kinship network that originate with an “other-than-human progenitor being.” The anthropological concept of totem derives from this ethnosociological term and is often used as a synonym for clan. The social, but even more, the political landscape was understandable, manageable, and manipulable to its inhabitants in terms of these nindoodemag. Yet this mode of figuring inclusion and exclusion, rights and responsibilities, was also flexible enough to accommodate the appearance of new people perhaps, in part, because Ojibwe social organization was changing from unilineal to bilateral descent as the single-clan villages were becoming multiclan settlements over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, catalyzed by the fur trade.

In the region south and west of Lake Superior, the combination of kinship norms and techno-ecological practices resulted in people being members of families, and families articulated with each other forming named bands that controlled territories. Bands were mobile, moving between seasonally resource-dense locations where they fished both in open water and through the ice, hunted terrestrial mammals, and gathered plant foods, especially wild rice, but also maple sap to make sugar, the last at least in the protohistorical and historical periods. There was also relative ease of movement between bands, often named after charismatic individuals, in that the kinship ideology that organizes social relations provides individuals with a resource that facilitates changing their allegiance and residence.

People who came to see themselves as a single culturally similar group over the course of the eighteenth century, and calling themselves “Anishinaabe” but also “Ojibwe,” extended from Ontario to North Dakota. They would become one of the largest indigenous ethnicities in North America and have been well studied by scholars from both within and without those societies for many years. Scholars manage the extent and sociopolitical diversity of this ethnic group by dividing them into the northern, southeastern, and southwestern Ojibwe, this last being the division of interest here.

Robert Ritzenthaler characterizes Ojibwe historic settlement pattern as “that of numerous, widely scattered, small, autonomous bands. Thus the term ‘tribe’ is applicable to the Chippewa-Ojibwas [these terms being versions of each other] in terms of a common language and culture, but it does not apply in the political sense that an overall authority was present.” Subsequently, indigenous ethnohistorian Theresa Schenck argued for the origin of the term and identity “Ojibwa” in “Ajijack,” the name for the Crane Clan, which would spread east and west from the fishing grounds at Sault Ste. Marie for its prestige value in the context of the fur trade.

The ethnonymic diffusion was catalyzed by the adoption of the Feast of the Dead and later the Midewiwin, or Medicine Lodge. Both of these ceremonial complexes effervesced with the fur trade. They actively reconstituted and reproduced boundaries and conceptions of communities, contra the materialist Harold Hickerson’s contention that these ceremonies are best understood as mainly expressive or reflective of sociopolitical change. This consolidation of an ethnic identity was also accelerated by the Iroquois destruction of Huronia in the 1640s creating a “shatter zone” throughout the Great Lakes region that caused Algonquian speaking peoples—several groups that would coalesce as the Ojibwe among them—to migrate west along both the northern and southern shore of Lake Superior, thus displacing resident Dakotas and Fox in the area that would become Wisconsin. Huronia’s collapse and the diaspora of their trade allies were an important event and process as North America was brought into the international fur trade.

Fur Trade

The story of the very origin if not also the dispossession of the Lake Superior mixed bloods and their assimilation to neotribal polities over the course of the second half of the nineteenth century has to begin with that intercultural exchange network we call the fur trade in North America, although it might be just as well be called “the cloth trade,” according to historian Susan Sleeper-Smith, since three-quarters of what was traded was cloth. There is a very large, daunting, and inviting North American fur-trade literature. For the purposes at hand, the literature is especiall...