![]()

1

Introduction

There is yet another and very important channel. … I mean the Welland Canal, cut across the Isthmus of Niagara in Upper Canada, which by uniting Lake Erie with Lake Ontario, affords a communication between the western lakes and the seas, either through the St. Lawrence, or by the Oswego Canal to Syracuse, and thence by the Grand Canal to the port of New York.

—Captain Basil Hall, Travels in North America

Captain Basil Hall was a renowned British naval officer and classic travel writer who visited North America in 1827 and 1828. During this time, Hall journeyed extensively throughout the continent, carefully recording his impressions of the advances in land and water transportation that heralded the ensuing canal age. As a captain of the Royal Navy who had spent nearly half of his life in service to the British Empire, Hall was fascinated with developments in transportation in the United States and Canada, and their impact on the age-old question of competition and commercial rivalry. After several weeks inspecting the Erie and Welland Canals, Hall offered some surprising observations on these rival transportation systems in North America. “At first sight,” he wrote, “it may seem that the Welland Canal, by offering superior advantages, will draw away from New York a portion of the rich produce of the state of Ohio, of Upper Canada, and of the other boundless fertile regions which form the shores of the higher lakes, yet there seems little doubt that the actual production of materials requiring transport will increase still faster … and that ere long additional canals, besides these two, will be found necessary.” Hall concluded that “the upper countries alluded to will derive considerable advantages from having a free choice of markets, as they may now proceed either to New York by the Erie Canal, or by the Welland Canal, down the river St. Lawrence, according as the market of New York or that of Montreal shall happen to be the most favourable, or the means of transport cheapest.”

Hall’s emphasis on the complementarities between the New York and Welland canal systems contrasts with much scholarly and popular writing about these canals and the larger stories around them—Canadian-American commercial competition, national rivalry, and westward expansion and market development generally. Whether in historiography or popular understanding, the story of the competing Canadian-American canal systems, and their broader narratives, seems a pivotal, settled, and almost legendary story with a clear message. The classical account begins with New York City-led economic expansion and America’s vulnerable military position along the New York frontier during the War of 1812. Seeking a leg up in the competition for the lucrative trade of the Midwest, and fearing another war with Great Britain and Canada, New York State built an interior canal to Lake Erie that bypassed British territory altogether. An alternative “Lake Ontario route” called for a canal around Niagara Falls that would have connected Lakes Erie and Ontario, and then linked the Oswego to the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers. But it was feared that once trade reached Lake Ontario, it would be lost to the St. Lawrence and Montreal market. By opting for the direct route between Lake Erie and the Hudson, Niagara Falls was deliberately left as a major barrier between Montreal and the interior. However, according to the same settled story, Canada swiftly responded to the Erie Canal by building the Welland ship canal between Lakes Ontario and Erie—a vital component in the St. Lawrence−Great Lakes water system that allowed Canadians to compete more effectively for the western trade, while also creating a market between the disparate provinces. Again, the United States went on the offensive by undertaking massive improvements to the New York canal system, but the introduction of the railroad, combined with the Panic of 1837 and continuing improvements to the St. Lawrence−Welland seaway, diminished the Erie Canal’s importance. Much canal scholarship continues to echo this conventional account.

This classic understanding of Canadian-American national rivalry and competition has been seemingly confirmed by twentieth-century developments. The successful Welland Canal became an integral part of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1954, but the Erie Canal sank into oblivion. Buffalo’s once vibrant position as a leading commercial port on Lake Erie was made obsolete following the enlargement and improvement of the Welland system. Even today, as New York State focuses on revitalizing the Erie Canal through tourism and recreation, the Welland Canal continues to serve as a viable part of the seaway, allowing large lake vessels and supertankers to navigate in and out of the continent.

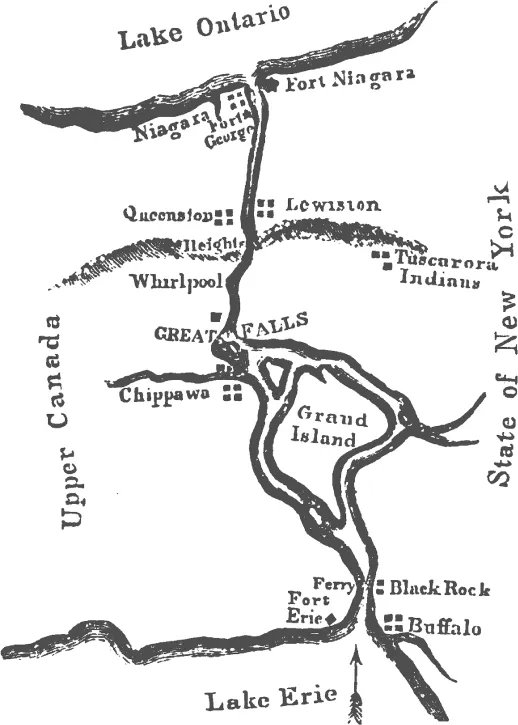

Of all the borderland regions in North America, Niagara’s location has been central in shaping the conventional story of conflict and rivalry between the Canadian and American transportation systems and their broader narratives. The Niagara River and Falls forms a natural barrier between the two peoples, and since 1783 Canadians and Americans found themselves on opposite sides of an international border that created the newly established British province of Upper Canada and the American Republic (fig. 1.1). As the water gateway to the West, the Niagara River and Falls held strategic value for both countries. As one historian observed “in the long-range commercial strategy of New York State” the Niagara barrier played a vital role in the Erie Canal’s building. The threat posed to national security during the War of 1812, and the questionable loyalty of many upstate New Yorkers who took advantage of Canadian markets during the protracted conflict, helped persuade the New York legislators that the Niagara River must remain a barrier because “they could circumvent it by means of the Erie Canal, whereas Montreal could not.” In Canada, the Welland Canal’s location has similarly been viewed as a direct response to America’s propinquity along the Niagara frontier during the 1812 imbroglio. “The memory of this conflict,” wrote one Canadian source, ruled against a canal at Niagara. Instead, in this same view, the Welland was deliberately built some considerable distance from the American frontier. Canada’s Niagara peninsula, which pointed “like a spear at the heart of the American union,” became a symbol for the contested canal age in this region.

Figure 1.1. The Niagara Borderland. John M. Duncan, Travels Through Parts of the United States and Canada in 1818 and 1819. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

It was also at Niagara that North America’s three most important canals—the Erie, Oswego, and Welland—connected and converged, making travel more accessible and opening the region to commerce, tourism, and improvement in general on a grand scale. Yet, the Niagara tourist industry, like the canals, has similarly been described in terms of competing national ideologies and interests. The story of this attraction, and tourism generally, has been seen through the lens of the natural wonder of the Falls itself, and the natural border it marks between the United States and Canada. For Elizabeth McKinsey, the power manifested in Niagara Falls becomes an icon of American prowess and patriotism. Patrick McGreevy, who has written extensively on Niagara Falls, argues in his thought-provoking article “The End of America: The Beginning of Canada”(1988) that the Falls have different meanings for the United States and Canada which can only be understood “in relation to two very different ideologies of nationalism.” Just as nation-centered history has shaped much writing on the canal age, scholars have discussed the tourist industry as distinctive and separate United States and Canadian stories.

This book tells a different story—one that examines the canal age from a borderland and transnational perspective. Despite the existence of the international boundary line and the ongoing geopolitical contest between the United States and Great Britain for control of the continental interior, Canadians and Americans embarked on a remarkable series of canal projects and other cross-border improvements driven not simply by continental rivalries and routings, but by the life, commerce, and connectivity of the Niagara region. Uninhibited by the international border, residents in upstate New York and Upper Canada built roads, bridges, postal and ferry services, and water transport systems that allowed for easier access to and around the Falls, while also creating an interlocking, interconnected transportation network in the Niagara−Great Lakes Basin. Personal and familial ties forged by the late loyalists, the existence of an early cross-lake trade, and the potential to develop commerce and tourism in the region contributed to the porosity of the border. By the War of 1812, and even during and after, lucrative commercial and cultural connections continued to be forged across the border. This book’s title, Overcoming Niagara, refers to the many ways in which Canadians and Americans mutually sought to overcome natural and artificial barriers, building an integrated, interlocking canal system that strengthened the borderland economy while also propelling westward expansion, market development, tourism, and progress generally.

A major premise of this book is that north-south transportation and communication linkages in the Niagara−Great Lakes region suggest little relationship between the international boundary line and the broader geopolitical interests of the United States and Great Britain. Nowhere was this more evident than during the building of the Erie Canal. Despite the broader narrative of Canadian-American commercial competition and rivalry, Upper Canada contributed to, and benefited from the Erie Canal in untold ways. Indeed, the historic debate over the Lake Ontario route’s challenge to the Erie Canal’s route revolved far less around a United States−Canada or New York−Montreal rivalry, than around the claim that the lake route might strengthen commercial ties with Canada while also sending substantial trade to the New York market. Many American merchants and shippers were awakened to the profitable, if illegal trade with Canada during the embargo and War of 1812 and in the postwar era became keen champions of the Lake Ontario route and closer Canadian connections. Even Erie Canal founder De Witt Clinton, who inspected both routes in 1810 as Canal Commissioner, spoke favorably of the Lake Ontario channel’s capacity to bring economic and personal benefits to both sides of the border. No matter where a person stood on the Erie Canal, or on which side of the boundary they resided, the advantages of maintaining close ties between the neighboring countries were rarely disputed.

While conventional histories emphasize the Erie Canal’s role in creating a canal boom throughout the United States, little attention is given to the American channel’s influence in sparking enthusiasm, and making possible, the construction of the Welland Canal in neighboring Canada. The Welland Canal projectors looked to the United States for support in their undertaking, knowing that the Erie Canal was almost completed, and that surplus laborers, engineers, contractors, technology, and capital would be available to assist in the upper province. Considered in its North American context, the Welland Canal (which unlike the Erie barge canal promised to serve large Great Lakes vessels) was welcomed as alleviating some of the early frustrations and delays being reported on the American channel, while at the same time opening a potentially more competitive and efficient means of moving American goods in and out of the interior. Conversely, the Welland Canal provided a major conduit through which Canadian goods could be transshipped to New York, thanks to the Erie and soon to open Oswego Canal. Whether destined for the Montreal or New York markets, the Welland Canal promised to facilitate trade on both sides of the border. It was this compatibility and interconnectivity that Captain Basil Hall spoke of in the quote opening this introduction where he described the New York and Welland Canal system in terms of a “a generous and legitimate rivalry.”

To focus on a uniquely Canadian or American canal age obscures the complex and nuanced history of the transportation era in the Niagara−Great Lakes region. The building of the Canadian and American canal systems was more about promoting cross-border linkages and associations than it was about conflict and rivalry. Nothing underscores the persuasiveness of the borderlands’ approach more than the story of the Oswego Canal. A major commercial link in the chain of inland navigation between the United States and Canada, the Oswego Canal was more than a feeder or lateral extension of New York’s grand Erie Canal. As often described in nation-centered history, the Oswego Canal was designed to offset improvements on the St. Lawrence−Welland connector that threatened to take trade from the American side. By opening a channel linking the Oswego port on Lake Ontario to the Erie Canal at Syracuse, trade would be re-routed back into the Erie Canal system, and America’s bid for the West restored. However, when viewed through the borderland and transnational lens, the Oswego Canal looks very different—not only was it a cord binding east and west, but an international waterway funneling goods through the Welland Canal in transit to both Canadian and American markets. A contemporary American newspaper celebrated the Oswego’s development announcing: “Another triumph of human ingenuity and wisdom is achieved. The hitherto insurmountable barrier of the Niagara is overcome and the waters of the Erie may now mingle with those of Ontario, bearing upon their bosoms the bounties of civilization and the gifts of the arts.” Meanwhile, across the border in Upper Canada, the Oswego Canal was being heralded as an important inland improvement, permitting American traffic from Lake Ontario and Erie to flow into the Welland Canal, bringing added utility and business to the Canadian system. In the following years, the newly fashioned Oswego-Welland line served as a major thoroughfare for inland merchants, travelers, and commerce on both sides of the international border. As will be demonstrated in detail in chapter 5, the Oswego’s building was not simply some strategic move in the larger imperial contest for military and political dominance of the interior so much as a complementary and logical component of the integrated Canada−United States transportation network emerging in this cross-border region.

Overcoming Niagara tells the story of how an emerging Canadian-American canal system promoted commerce, market development, tourism, and progress generally in the Niagara−Great Lakes basin. Though it deals with commerce and trade, it is not fundamentally an economic study so much as a broader history of development that traces the many linkages that transcended the border and helped shape a transnational region. While Overcoming Niagara shows that a significant cross-border trade occurred in this porous region, trade data on which economic studies depend was not systematically recorded for the period under review. Scholars note for example, that in Upper Canada “no systematic records of exports or imports were kept prior to 1849” and similar problems relate to trade data on the American side. However, as more than one scholar attests, export trades and their related industries do not necessarily or only refl...