![]()

1

Animal Life and Rural Labor

Literary and Material Resistance in Biopolitical Britain

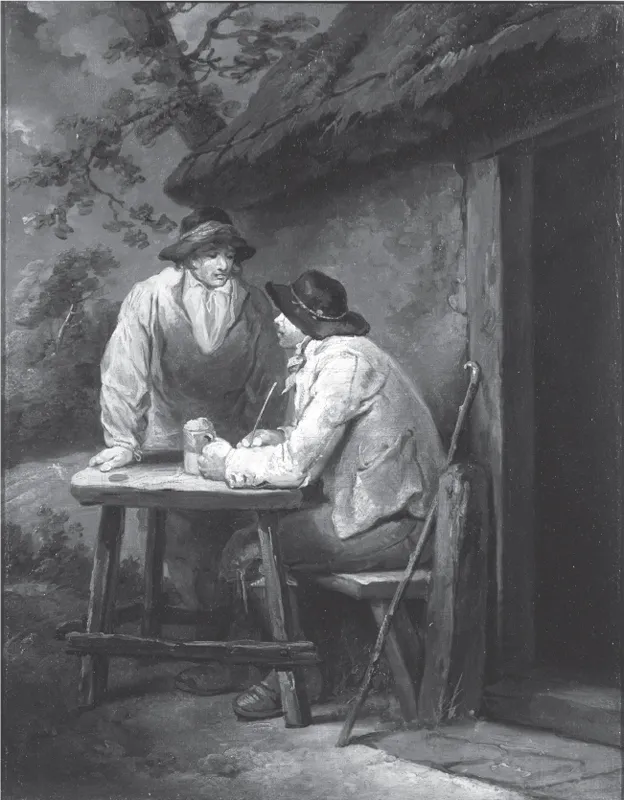

In George Morland’s painting Outside the Alehouse Door, two men are talking outside a rustic thatch-roofed alehouse. One man sits at a simple outdoor table and holds a beer and a pipe. His companion has his hands on the table and leans toward the seated man as if engaged in earnest conversation. The man seated with his beer is slightly turned away from the viewer, and the brim of his hat covers part of his face. Light focuses the viewer’s eyes on the men while a darker atmosphere surrounds them, including a darkened doorway, shadows cast by the roof and a tree, and a sky with mixed weather of dark and light clouds. We are left to wonder what these men could be discussing.

Known for his agricultural paintings of labor and leisure, Morland is one of the most prodigious painters of the Romantic period. His work was well known throughout the nineteenth century, and John Barrell’s The Dark Side of the Landscape brought Morland to contemporary notice. As Barrell notes, such wondering about the conversation between the men at the alehouse turned to anxiety for at least one of Moreland’s Romantic-period biographers. William Collins, in his 1805 Memoirs of a Painter, describes the painting as “[a] group of English figures regaling themselves, which, like true sons of liberty, they seem determined on in spite of all opposition.” Collins’s use of the term “true sons of liberty” carries with it the connotation of populism and radicalism, which coupled with “the word ‘English’ has a disturbing political implication. He [Collins] recognizes these labourers as ‘free-born Enlishmen,’ men who are represented as actually resisting—they are ‘determined’—the demand that they should accept the status of mild, temperate, industrious, submissive labourers” According to Collins’s sensibility, rather than drinking beer, these men should be figures of industry, and like proper laborers in picturesque paintings, they should be working in the fields.

Figure 1.1. George Morland. Outside the Ale House Door. 1792. Tate Gallery.

Barrell explains that with one beer between them and their serious demeanor, the men are not “regaling themselves.” Rather, discomfort over the ale comes from “this jug of ale [as] a symbol of their indiscipline and revolt—[because] it is not diluted by any reassuring passivity of attitudes. … their little money would be better spent on the wants of their families than on their own coarse pleasures; and that pint becomes for Moreland’s critics a signpost on the road that leads from idleness to insurrection.” A turn to biopolitics—or biological life made political—extends Barrell’s line of thinking and sees it as more than anxieties over the political capacities of the laboring class. The worker is drinking beer brewed from a grain in the fields in which he has toiled or from other fields nearby. It is a local product of his labors and those of his fellow field hands. On the eve of war with France and with perceived distance between landowners and field hands, the men in Outside the Alehouse Door must place the sweat of bodies in the field, their labor, and their liberty in relation to a larger political world of a growing nation. The beer is in contrast to French wines, which became the fashion of landowners and was derided as a political betrayal by William Cobbett and other class-conscious critics of rural life. As Robert Bloomfield laments, the landowners now “violate the feelings of the poor; / To leave them distanc’d in the mad’ning race, / Where’er Refinement shews its hated face.” What these men at the alehouse door eat and drink, how the product of their labor is used and to whom it is distributed, where they are allowed to congregate, and how they are allowed to use their “free” time are all matters of biopolitics as the social body peers into the biological life of a people.

Pipe and beer as signs of Englishness appear some years later in Edwin Landseer’s painting Low Life, where a stocky dog with wide chest and thick jaw sits at the worn wooden doorstep of his master’s home, loyally awaiting his return. Beside him rests a mug of beer and a pipe. Through the cultural signification of objects, the animal is interpolated within the same social, economic, and labor world as his master. The political connection between beer, bully breed dog, and England is evident in James Gillray’s cartoon Politeness. A stout Englishman sits with his pint of beer in his hand and his bulldog at his feet. Behind him hangs a large cut of red meat on a hook. He stares down at a Frenchman seated to his side. In contrast to the beefy Englishman, the thin Frenchman wears refined clothes and a wig. He holds a container of snuff rather than a British beer. At his feet is a mousy dog cowering from the growling British bulldog. Where the Englishman has large slabs of meat behind him, the Frenchman has two small frog legs.

Returning to Morland’s painting, to further the contrast between these field hands and the landowners, where “Refinement shews its hated face,” a walking stick rests next to the seated man. From its appearance, the stick is likely made from hawthorn or blackthorn—both of which were used as barbed hedgerows to reinforce land enclosure in a fence-like fashion. A walking stick cut from the barriers to liberty of trespass reveals a defiance against laws that restrict the movement of people and forecloses the use of common pathways. A knotted, thorny shrub changes value. It transforms from plant to a fence that reinforces state and local laws. In the hands of a field worker, it becomes an object of defiance of such laws. The walking stick refashions the biopolitical tool from fence to instrument of motility.

One can read bodies, their vitality, and their capacities by creating new assemblages of material objects; dogs, beer, and earnest laborers set in a rural environment create a mosaic of a political life that affects the very biological being of the dog and workers, their food, and their rural ecology. Maurizio Lazzarato summarizes how forces become a power, in this case biopower, and how such power is used by the state as biopolitics. According to Lazzarato, “biopolitics is the strategic coordination of these power relations in order to extract a surplus of power from living beings. … Biopower coordinates and targets a power that does not properly belong to it, that comes from the ‘outside.’ Biopower is always born of something other than itself.” Moreland’s painting, along with Landseer’s and Gillray’s, show how the “surplus power from living beings” is called upon for political ends. Collins’s uneasiness about the leisure of laborers in Outside the Alehouse Door reveals how the life of the worker is circumscribed to toil in the fields. Any surplus time and energy carries with it the social demand that it be spent in moral and industrious pursuits of benefit to the family and society. Ale and beer serve as ambiguous signs: they can represent the well-being of a people who have the ability to expend time in drinking but also the possible careless or riotous mood drink can induce.

The dogs in Low Life and Politeness are tough-looking, muscular beasts. Their attributes of loyalty and ferocity move from dog to human owner. In this move, the canine is part of a fearsome animality within the Englishman. The politics of muscular bodies, what they eat to build themselves, and how these bodies can be used for ends of power and the state are part of what Lazzarato means when he says that “biopower is always born of something other than itself.” Biopower attempts to harness the forces within masses of living bodies toward civil and social ends.

As will be evident throughout this book, bodies insist, resist, and weigh. Biopower causes something new to emerge: populations, labor expenditures, food intake, economic outputs, and so on. But the “something else” from which biopower extracts its ability does not have to abide passively. While biopower is a mode of production by assembly and assimilation of forces not properly its own, resistance to biopower creates yet other modes of production: “Foucault is interested in determining what there is in life that resists, and that, in resisting this power, creates forms of subjectification and forms of life that escape its control.” Friction to state machinery and biopolitical schemes creates other modes of living and dwelling. Such resistance is a line of flight from the formation of the modern state and its ability to “make live and let die.” Each chapter in this book provides a reading of not only apparatuses that create biopolitical subjects, but also alternative forms of life.

In his essay on public health in the eighteenth century, Foucault sketches a methodology for reading biopolitical apparatuses. He proposes to examine “the whole of a complex material field where not only are natural resources, the products of labor, their circulation and the scope of commerce engaged, but where the management of towns and routes, the conditions of life (habitat, diet, etc.), the number of inhabitants, their life span, their ability and fitness for work also come into play.” I apply a similar methodology of investigation where material fields meet representation and apparatus of production (biopolitical and otherwise). Some of the texts, such as Malthus’s and Adam Smith’s work, are symptomatic of the biopolitical apparatus, while other texts, such as the labor class poetry of Bloomfield and Robert Burns, bear witness the workings of biopolitics “in the field,” as it were. Still other texts provide alternative assemblages and ways of dwelling over and against interpolation by the state, as is evident in the James Hogg’s rural tales and select work of Edwin Landseer.

By way of illustration, consider another brief example of material life and politics from the Romantic period, this time taken from the twenty-fifth chapter of the Book of Deuteronomy: “Thou shalt not muzzle the ox that treadeth out the corn” (Deuteronomy 25:4). During the Romantic period, this biblical phrase was used by advocates of gleaning to justify this common practice. For centuries, workers and their families have gathered for their own use the sparse remaining stalks of grain from harvested fields. Gleaning functions outside the wage-labor system but within the social economy by which families supplement their provisions and income. Taken literally, the biblical phrase invites working livestock to partake in the fruits of their labors, which otherwise become commodities for humans. The passage expands the community and economy by which humans and nonhumans dwell. By using the passage from Deuteronomy as a rhetorical tool for justifying gleaning, advocates of the practice collapse the human–animal distinction, bringing both together as beasts of burden. Although the physical labor of humans and animals was part of the economic system of agriculture, the beasts of burden are claiming that their physical labor should feed their biological need. The ox eats the corn to sustain further milling, and the farm hands and their families glean grains to keep hunger from their doors. The biblical passage pits biological bodies and their capacities against economies that overlook the needs for sustaining life.

Those who opposed gleaning sought to bring the labor practice under a singular system of accounting. In it, not only the work of gathering grain but its food value, too, would be measured within the quantifiable sums of a monetary economy and capitalist market. Along with gleaning, food riots were a way of rebelling against the market-driven system. Agricultural laborers believed it their social right to be able to buy the bread made from the grains they grew and harvested. These concerns of life, agriculture, and capitalist economy are addressed in chapter 2, but here I would like to develop the utility of biopower as a concept by which to reevaluate less known literary and cultural texts of the Romantic period. Beasts of Burden explores how a number of interested parties and systems attempted to manage not only labor practices but more broadly the health and well-being of the humans and animals who worked the fields and how these beasts of burden resisted such systems. The book is a proof of concept for how the extension of social power into biological life has far-reaching implications for the Romantic period and for scholarship on aesthetic and cultural texts of the period.

Michel Foucault’s early work on disciplinary societies accounts for the regulation of labor practices as a regulation of bodies. These are “techniques of power that were essentially centered on the body, on the individual body.” For agricultural labor during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this means everything from pricing systems for labor to technologies such as new seed drills and plows; it includes soil regeneration by way of crop-rotation systems and the use of manure. Each of these mechanisms, large and small, changed how the laboring body functioned in the fields. However, the disciplinary society does not adequately describe the relationship among commodity markets, governmental practices, and the livelihood of laborers. Gleaning, for example, means not only labor practices but also a regulation of food, life, and livelihood both on and beyond the scale of the individual body.

In the mid-1970s, Foucault began describing a different modality of power that he saw as “the greatest transformation political right[s] underwent in the nineteenth century.” According to Foucault, various technologies, apparatuses, and governmental structures cohere in a new power: “the power to make live and let die.” Governments have long had the power to kill, including sentencin...