![]()

1

Body Identifications

The Movie Screen and the Mirror

Audience identification with movie stars is far from new. Nor is the power of screen bodies to establish, shape, and propagate mass cultural body ideals. Both can be traced back to the early days of Hollywood following World War I when fan magazines such as Photoplay found a ready market in the demographic favoring young Americans as the major moviegoing audience, much like today.1 This in turn gave rise to the widespread circulation of a body ideal defined by youth and slenderness as well as the marketing of products to achieve it, such as La-Mar Reducing Soap and Weil's “Scientific Reducing Belt,” commercial ancestors of today's multibillion dollar weight-loss industry. Throughout the 1930s Hollywood stars such as William Powell warned women to avoid looking “fat and forty” to keep their men from wandering, while Jean Harlow endorsed Woodbury's Facial Cream to rid her face of dreaded wrinkles.2 In this way the professional imperative for Hollywood's leading ladies to stay slender and youthful was transmitted to female moviegoers via a growing consumer culture which encouraged fan identification with the practices of body vigilance and control: “The rhetorical strategy underlying youth advertising in early fan magazines suggests the panopticon,” writes film scholar Heather Addison: “All parts of people's bodies were under scrutiny at all times, by themselves and others.”3

This conflation of youth, sexual desirability, slenderness, and self-scrutiny located in and radiating out from Hollywood movie culture was to repeat itself throughout the rest of the twentieth century. Movie studios invested the images of their stars with enormous visual power and glamour; these idealized bodies in turn became commodified both for the movie industry as well as the thriving beauty consumer market it fed. Notes film scholar Annette Kuhn: “Women's bodies and selling were identified: representations of women became the commodities that film producers were able to exchange in return for money.”4 Seeking to imitate the “look” of their favorite movie star, female moviegoers would purchase not only tickets to see their latest films but also the self-care products and accessories associated with their image. Film historian Rachel Moseley, for example, has traced how the personal styling and shopping behavior of British working-class women in the 1950s and '60s were inspired by the Hollywood persona of Audrey Hepburn, whose elegant style enacted for them the possibility of social transformation through fashion.5

Perhaps the most well-known cultural studies of female screen identification are those of Jackie Stacey, whose work marked the shift from earlier “cine-psychoanalytic” theories of film spectatorship to sociohistorical investigations of movie audience reception. Drawing upon memoirs of British women about their responses to Hollywood stars during World War II and the following decade, Stacey's ethnographic study discovered many examples of what she called “identificatory fantasies,” which ranged from religious devotion to a screen “goddess” such as Joan Crawford all the way to total psychological escapism into the high society world of Katherine Hepburn's films.6 One of the most poignant examples of screen identification Stacey cites is a reminiscence from a filmgoer who would gather with her schoolmates at an open coal field to build mounds of dirt dubbed the “Beverly Hills,” each girl fashioning her own “mansion” and pretending to be her favorite movie star.7

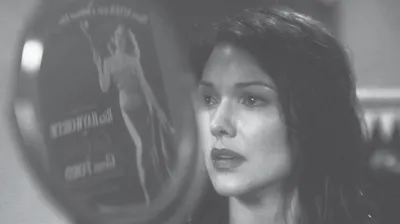

Particularly relevant in terms of Hollywood's potential to influence eating disordered behavior are the identificatory processes of imitating, copying, and consumption documented by Stacey whereby the female moviegoer actively seeks to align her own identity closer to that of an admired star. In this way the “look” of the movie star on the screen embodies an aspiration for the viewer which is then internalized in the form of actual cognitive beliefs and behaviors—thus not merely changing hairstyles or hats or purchasing endorsed beauty products but taking on the attitudes and personality “type” each star represents in their screen persona. In this way, notes Stacey “The self and the ideal combine to produce another feminine identity, closer to the ideal”8—a kind of reinvention of the self to incorporate the admired star image. A striking postmodern reference to the merging of both body and identity with the image of Hollywood screen icons appears in David Lynch's Mulholland Drive (2001) when a mysterious woman who is suffering from amnesia adopts the first name and personal style of Rita Hayworth. The film visually captures this moment of identification in an extraordinary shot: as the woman gazes at her own face in the mirror the viewer also sees the reflection of a poster on the wall behind her which displays Hayworth performing her famous femme fatale role in Gilda, the 1946 film noir.

But these same processes of screen identification operate offscreen as well, where they can have a direct impact upon the eating behavior and body image of the individual moviegoer, just as it did in the case of Courtney, a freckle-faced sophomore in my psychology seminar entitled “Eating Disorders in College Populations.” Barely five feet tall, she tried to keep her weight under one hundred pounds to maintain a size zero but still struggled to fit into the clothes that she believed made her look “hot.” After her current boyfriend broke up with her during the course of the semester, Courtney told me she sought inspiration from a popular romantic comedy she had recently seen:

In The Break Up Jennifer Aniston is so beautiful and has the most amazing body. She's incredibly thin and looks absolutely adorable in these tank tops and slinky little dresses—not one belly bulge or ounce of flab. When I saw it I had just broken up with my own boyfriend and was trying to think of ways to get him back. I took Jennifer Aniston's idea to make him jealous like she did to Vince Vaughn and thought if I looked as good as her maybe it would work. I started to skip breakfast and lunch and go to the gym twice a day all in my head thinking about how I wanted to look like Jennifer Aniston in that movie and maybe just maybe when my ex saw me he would want me back.

Figure 1.1. Borrowing an identity in Mulholland Drive.

Courtney's endorsement of the belief that slenderness and sexiness are necessary prerequisites for empowerment as an object of male desire indicates that she has already internalized contemporary discourses about the body ideal. Thus, she is primed to identify with the movie's representation of that ideal in the image of Aniston's body—so much so that she seeks to copy it through diet restriction and extra-rigorous workouts. Embedded in Aniston's super-thin body is the film's message: to get your man back you have to look perfect—and be perfectly thin, a construction of gender and power relationships that narrowly defines female agency just as it narrows the body ideal to the size zero Courtney yearns for. It is also important here to bear in mind that the degree of internalization—in other words just how fervently viewers believe in the thin ideal as synonymous with self-control, success, and attractiveness—is frequently cited in media exposure research as the key to body image disturbance among girls and women.9

In order to better understand the formation of such compelling identifications with the body ideal represented by movie stars it is also helpful to revisit the work of feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey. In her groundbreaking 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Mulvey described the “apparatus” of the cinema as a patriarchal construction in which the camera produces an image of the woman's body as a source of voyeuristic pleasure for what she posited to be a male spectator.10 The image of the woman's body is positioned as a performing spectacle in the foreground of the movie frame, an object of erotic contemplation both for the male characters in the narrative as well for the spectator in the audience. Her body is coded for what Mulvey calls its “to-be-looked-at-ness”11 by the controlling gaze of the camera, which uses the cinematic devices of framing, lighting, and shadows to “freeze” her image on a flattened spatial plane while in contrast, the male characters move actively within the deeper three-dimensional spaces of the screen.

In a departure from Mulvey's focus, however, here we are concerned with what effect these cinematic conventions might have on the psychological and behavioral responses of the female spectator as the camera exaggerates the long slender legs and zooms in on the toned arms and narrow hips of action film warriors and makeover movie heroines, eroticizing and glamorizing bodies that represent the ideals of dietary restraint and control—an effect that became part of the story of one young woman I treated for bulimia. Cindy was twenty-six years old, working as a paralegal in a local law firm and planning to go to law school. The tallest girl in her class throughout elementary and middle school, she had always had a troubled body image, feeling herself “too big and bulky,” which soon turned into a perception of herself as overweight. In her affluent suburban high school she felt less feminine than the “tiny” popular girls and didn't date. Desperate to reduce her size and failing to stick to ever harsher diet regimens, she began to experiment with purging and eventually became bulimic. During the course of our therapy work, she recalled a defining moment in the early history of her eating disorder:

I was just about obsessed with the movie Cruel Intentions, in which Reese Witherspoon and Sarah Michelle Gellar were beautiful, sexy, and thin. It seemed the whole focus in the movie was on their fantastic toned arms and legs, and of course completely flat abs, and I just couldn't stop focusing on those bodies. I think it was their sex appeal that I coveted. I wanted to be the girl turning heads and getting guys. And by throwing up almost everything I ate for a little over two years, I became that girl. I can actually say I was my female ideal: I had big boobs, a nice flat stomach, and at five feet eight inches I was pretty striking.

After leaving home for a big urban university Cindy began to feel more socially confident and developed a close relationship with a college boyfriend. Eventually her bulimic symptoms remitted, only to reappear after graduation when the relationship ended unexpectedly. She described a long painful period during which she would return to her apartment every night to binge on ice cream and cookies, eating until she could barely walk and finally falling into an exhausted sleep after “purging it all out.” More recently however, she has begun to move toward self-acceptance in general and of her “natural” body size in particular. She reports feeling less compelled by the thin ideal and is questioning the conventional values embedded in its screen representation:

It's funny but I don't feel so driven by gorgeous movie stars anymore. When I was younger I really believed what they were always saying—that only skinny women could be sexy and have a life. I know now that's just not true. When I was making myself throw up and lost a lot of weight maybe I got all the male attention I always had wanted, but I was mostly treated as a sexual object and nothing more. I dumbed myself down and lost my own opinionated personality; I became just a shell of my real self. Now I'm feeling happier with who I am because I know I have more to offer guys and the world than my body. My body is for me, not for them.

Mulvey also applied the theories of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan to her understanding of the process of screen idealization of the movie star. Lacan described what is known as the “mirror stage” of ego development during which a baby is first held up before the mirror and encounters an image of his or her self that seems more whole and integrated than s(he) feels inside. Mulvey used this notion to explain the ambivalent relationship the spectator has with the movie star: “Hence … the birth of the long love affair/despair between image and self-image which has found such intensity of expression in film and such joyous recognition in the cinema audience.”12 In other words, the movie star is like that ideal image in the baby's mirror—more powerful and larger than life because of its cinematic brilliance but enough like the spectator to allow for the pleasurable fantasy of identification. For the contemporary female moviegoer, however, the pleasure is increasingly met with an equal measure of discouragement—and even despair—at the gap between the screen image and her own image in the bathroom mirror where she gazes at her body, anxiously inspecting any offending fleshy bulges and bumps and sagging skin.

Thus, the golden glorious tall and tight female bodies on the screen are the ideal against which women measure their own bodies—and find themselves lacking. Such culturally driven body insecurity takes its most extreme form in the distorted body image of anorexic patients who look in the mirror at their emaciated bodies only to see themselves as grotesquely fat. But for the vast majority of female viewers who are not suffering from the symptoms of clinical eating disorders, the effects of the self-ideal gap can be sufficiently troublesome because they create body dissatisfaction, the risk factor that plays such a key role as we try to connect the dots between the impact of movie screen images on unhealthy eating behaviors. Here for example is the response of Samantha, another student at my university, to the gap she perceives between her own body and that of Angelina Jolie:

My favorite movie star is Angelina Jolie. She has the most incredible body and even though the gossip magazines say she's anorexic, she always looks so hot—especially after all those babies. Even my boyfriend tells me he's turned on by those fabulous full lips and great boobs; I would die for a body like that. Maybe even if I had to become anorexic for real! When I went to see her in Mr. and Mrs. Smith I threw out the popcorn I'd just bought (it had butter on it and everything) and didn't eat a thing all the next day. Later I kept thinking about that movie and started to watch what I ate a lot more and noticed a difference in my food, not letting myself eat anything the tiniest bit fattening. It also changed how I saw my own body because the movie made me feel like I don't live up to what is expected to be a sexy woman. I get so bummed about how I look to myself in the mirror compared to someone like Angelina.

Not only is Samantha's perception about her body negatively affected by this comparison but she then goes on to contemplate the benefits of anorexia, a sobering echo of the media exposure research cited previously that viewers most influenced by slender body images are more likely to endorse disordered eating behavior as a means to a much-desired end. And in fact Samantha's fantasy about anorexia is something I frequently hear from both students and patients struggling with weight issues; as one woman confided to me not long ago: “If only I could become anorexic just until I reach my goal weight—and not die in the process!”

Connected to this self-ideal gap is the increased risk of media exposure in those vulnerable girls and women most affected by the process identified by media scholars as social comparison theory: “It could be argued that social comparisons are at their most problematic when there is a large discrepancy between the person's actual (or perceived) self and his or her ideal self, resulting in efforts being made to attempt to close the gap.”13 And for these individuals who constantly check out each other's bodies—both overtly and covertly—at the gym, the mall, or the office, body comparisons don't stop when the lights go out in the movie theater. Not surprisingly, moviegoers who are more compelled in the course of their everyday lives to compare their bodies to others tend to see in images of their favorite movie stars harsh commentaries and critiques of their own bodily and dietary failures. At times these invidious comparisons are so powerful that they actually intrude upon the viewer's pleasurable immersion into the world of the film. Here for example is how Kristi, a twenty-three-year-old graduate student, described her internal experience while watching a surfing movie she had rented from the video store:

I first saw that surfing movie Blue Crush when I was still in high school, and even though I know it's like junk food I got it out again last night. Each time I see it I still think how great it would be to look like Kate Bosworth and also have her athletic ability. Now I consider myself pretty fit, I go to the gym five times a week and lift weights, but I do not look like Kate in any way, shape or form. Watching her surfing the waves in her bikini makes m...