![]()

Chapter 1

Mexican Origins

Every superhero needs an origin story (or two or three if a reboot is in order), and Capitán Latinoamérica is no different. When the humble taxi driver is asked to don the mask and uniform of the superhero in El Man, he is compared to Gandhi, Jesus, Che Guevara, and El Chapulín. When Mirageman storms the streets of Santiago to kick ass and take names, the newspapers call him a Chilean Chapulín. When a somber Ráfaga explains the mission of Nafta Súper in Kryptonita, an antagonist tries to belittle him by calling him “Chapulín.” When Chinche Man first appeared as a character on television, the only phenotypical indicator of his superness (as his physique is lackluster at best) was the luchador mask he wore to hide his face. Similarly, Alfonso Sahagún Casaus’s El Alambrista is a superhero who defends the rights of undocumented migrants crossing into the United States from Mexico in El Alambrista: The Fence Jumper (2005) and El Alambrista: La Venganza (2014). His costume is a cape and a mask in the colors of the national flag that he wears while wrestling in the ring and while fighting vigilantes who seek to create a legion of monsters from the unsuspecting migrants. Yet it is not solely fictive contemporary superheroes that link their identities to earlier characters or types taken from a Latin American popular imaginary: the Honduran superhero-cum-social worker, Súper H, wears the shirt of la selección in addition to a wrestler’s mask adorned with the five stars of the national flag. When I asked him why he wears a wrestling mask, he replied that wearing it made him “want to fight for a better Honduras” (“querer luchar por una Honduras mejor”); he also added that the idea came from watching his favorite superhero, El Santo, fend off werewolves, vampires, and robots.

The examples above demonstrate that should the contemporary Latin American superhero attempt to trace his or her DNA through one of the many swab-by-mail services that promise your genotypical history, he or she would discover at least three distinct heritages. First, and as is the case with most global superheroes, our Latin American superbeings would display vestiges of their Anglo forefathers. Either inspired from print or celluloid artifacts, contemporary Latin American superheroes often emulate, deconstruct, or resemanticize US and Hollywood heroes, taking the DC and Marvel juggernauts as their base-text, reformulating their aesthetic, axial, and political qualities to conjugate the local.

Second, a large percentage of their DNA would be traced to the wrestler El Santo (and a cohort of other fighters such as Blue Demon and Mil Máscaras), who featured in films from the late 1950s onwards. Aside from providing an aesthetic model to follow (the distinctive mask, the beefy physique), these wrestler-superheroes provide an axial model for the contemporary superhero as an hombre de bien; that is, his primary superpowers are his honor, wisdom, and faith. This is evident in characters such as El Man, Chinche Man, and even Capitán Centroamérica in his final incarnation, as their superhuman strength and speed are often subsidiary to their unimpeachable moral character. The latter is often the one true superpower, replacing physical and psychic strengths, or the ability to conjure nature’s elements: to be virtuous and fair is more powerful than anything else, suggesting that the didactic element in these films is less fantastical and more explicit, as any viewer could (in theory) become said hero.

Finally, their DNA results would show close affinities with the parodic ethos of El Chapulín Colorado, the star of a homonym television show that aired from 1973 to 1979. Sartorial, aesthetic, and narratological parody are at the core of the majority of contemporary superhero productions, which encourages both a critique of the extradiegetic world, and an examination of North-South relations (that is, of the dialectic between hypo- and hypertext). As El Chapulín showed millions of viewers in its initial run and reruns, parody can be an effective and popular mechanism for reading the world.

There are several points of contact between these two superheroes. Both characters were originally produced in Mexico, birthed from a distinct sociocultural milieu and mediascape that was propitious for the creation and dissemination of popular characters based on the North American character type and narrative genre of the superhero. Mexico, after all, was the center of commercial Latin American cinema during its Golden Age from the 1930s to 1960s, and was not only home to famed directors and film stars, but also steadfast in its development of genre film.

Importantly, the cinematic ecosystem of the Mexican Golden Age transcended national borders, becoming the cinema par excellence in the Spanish-speaking world as its features and stars were exported globally. The spreading of Mexican cinema stimulated a correlative osmotic nature, where the industry was quick to adopt production and narratological conventions of its Northern neighbor—it was a contact zone between Anglo US cinema and a Latin American cinema. It is therefore unsurprising that the superhero of contemporary Latin American moving images finds his first steps within the Mexican mediascape.

That being said, the superhero tends to appear at moments of crisis, when the sociocultural telos is at its most fragile and the political zeitgeist is one of polar contradictions. Superheroes dominate the collective imaginary when normal heroes no longer suffice to give us a sense of stability. Superheroes galvanize the popular spirit when the axial and ideological pillars that sustain our daily lives come into question. Latin American superheroes are no different (as we will see in later chapters), and the early Mexican superhero boom follows this hypothesis, as the genre appears and gains massive popularity during two distinct crises. First, the Santo and company films appear at the very end of the Golden Age, at a moment when the Mexican film industry entered a crisis stage due to antiquated and unsustainable funding structures and increased competition from Hollywood in a post–World War II global and ideological market for cinema (Ramírez Berg 37). The Santo films (along with other popular genres such as the fichera genre) were churned out like churros to compensate for the economic woes of a once-strong industry (Schroeder Rodríguez 116), appealing to a popular urban audience that was not always reflected in the Golden Age oeuvre.

Second, the superhero-wrestler genre and the parodic Chapulín emerge at a politicoeconomic crux, when the Mexican Miracle was in full swing. The Miracle describes a period of approximately three decades when the economy—due to the successful implementation of import substitution industrialization and the proliferation of the petroleum industry—was on a perpetual rise. A thriving economy brought about significant demographic changes, including growth in income per capita, improved health and education metrics, and, importantly, rapid urbanization (Alba and Potter 47). The positive trajectory of the economy was, however, contemporaneous with the rise of an antiauthoritarian sentiment characteristic of a global ennui in 1968. In Mexico, students in the capital organized protests and strikes demanding increased civil liberties and a more transparent and democratic government (the ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional had been in power since the end of the Revolution). Their requests for change were met with impunity, as the military and police of president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (and his secretary of the interior, Luis Echeverría Álvarez) commandeered an indiscriminate massacre on October 2 in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco. The ensuing government cover up only served to highlight the episteme of crisis that Mexican civil and intellectual life had entered, albeit while enjoying unprecedented economic success.

In sum, the cinematic and televisual Mexican superhero is birthed in a moment of polyvalenced instability, characteristic of the genre’s genesis and proliferation across national and temporal frameworks. The genre takes on multiple roles during the crisis episteme (including a narrative representation and hashing out of conflicting political positions), though its principal impulse is to maintain a status quo under siege. I begin this chapter with a study of several cult films featuring El Santo and other wrestlers to lay out the characteristics of the wrestler-as-superhero trope, paying attention to the constructs of ideology, gender, and politics and how they are conjugated in the genre. In doing so, I am interested in delinking the character from a purely luchador and mexploitation genealogy and to instead suture him to the superhero genre proper. In doing so, I am not suggesting that the wrestler-as-superhero film is mutually exclusive from the luchador genealogy that Doyle Greene, Robert Michael Cotter, Raúl Criollo, José Xavier Návar, and Rafael Aviña have so expertly traced. Rather, my aim is to understand El Santo primarily as a superhero analogous to US heroes that demonstrates idiosyncrasies based on the cultural specificity of his place of origin. This, in turn, would explain his being source material for contemporary Latin American superheroes that are not wrestlers. I follow this section with an exploration of other characters that were not necessarily linked to the world of wrestling, including female superheroes and characters that were more superhero than wrestler, before studying the Kalimán series that successfully adapted a popular radio and print hero to the screen. To conclude, I analyze El Chapulín and its recourse to parody as a narrative and aesthetic mode to portray the superhero. I focus on the powers that this hero lacks, linking the trope of the parodic superhero to issues of gender hegemony and political critique, focusing specifically on US-Mexico relations. In this section, I contrast the hypervirility and exaggerated physique of the luchador vis-à-vis the superhero-as-parody trope of El Chapulín, to demonstrate how these polar opposites conjugate the semantics, aesthetics, and ideology of the contemporary Latin American superhero character.

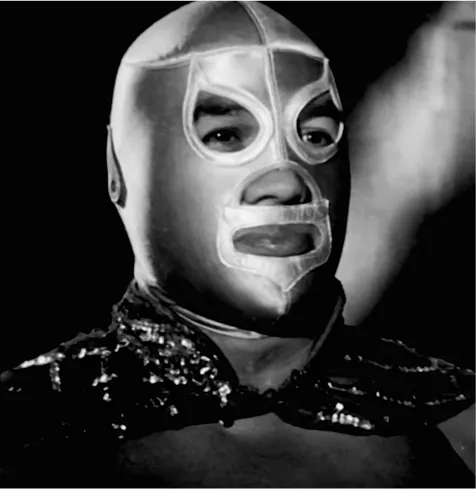

El Santo as Superhero

No other image or icon is as quickly identified by a global audience with Mexico and its collective identity than that of the masked luchador; at times, all we need is the mask itself sans body, a vague outline of a face with exposed eyes that semanticizes an entire history. And perhaps no other mask is as iconic as the silver one worn by Rodolfo Guzmán Huerta in a career that spanned five decades. Born in 1917, El Santo began his career fighting under his own name, as a rudo or heel, in 1934 just after wrestling was imported as a sport and spectacle to Mexico by Salvador Lutteroth. Like others in the sport, the wrestler went through a series of personas to settle on “El Santo” in 1942. The name at first was paradoxical, as the wrestler continued in his character as a rudo, but then slowly evolved as he gained a mass-media presence by starring in comics produced by José Guadalupe Cruz. First appearing in 1952, Cruz’s El Santo, el Enmascarado de Plata was a massive hit (Lieberman 5; Rubenstein 572). These comics “used photographed still images and captions to tell a story much like the drawn panels in traditional comic books and comic strips” (Lieberman 5). They were not fotonovelas, that is, comics composed of live-action photographs arranged to tell a story, but rather used the technique of fotomontaje that combined photographs and drawings in hybrid format that transgressed the idioms of veracity and fantasy employed by the strictly photographic or drawn (Wilt, “El Santo” 206). Importantly, the print medium “offered the first construction of Santo as the hero of the Mexican people, endowed with superior intelligence, morality, and almost superhuman powers” (Lieberman 5). The transmogrification of the rudo to comic book superhero (thus effectively inserting the wrestler figure and El Santo within a genealogy and genre of the superhero comic book) “manufactured the popular image of Santo as a superhero fighting the forces of crime and evil threatening Mexican society, and also served as a basis for the Santo movie formula” (Greene 51). Importantly, the comic book hero was not a wrestler now placed in crime-fighting scenarios, but was an altogether different protagonist that benefited from the aesthetics and popular consciousness of lucha libre.

Figure 1.1. The silver-masked icon.

The plot of Cruz’s comics was simple and recyclable: a layperson (usually either a lower-class boy or middle-class woman) facing some sort of calamity is widely ignored until a wise acquaintance tells them to get help from El Santo (Rubenstein 573). The wrestler would listen to them in his urban office, and then go off and fight the crooks (sometimes real, other times supernatural). In between, of course, he would also wrestle in stock images taken from real Santo fights. The comics effectively place the wrestler within a recognizable narrative and visual genre that borrows heavily from the superhero comic, replacing a working-class wrestler who earned the ire of the public when purposely flouting the rules of the ring with a sleek superhero that evoked characters from US comic books. As Anne Rubenstein notes, “El Santo wore a suit … and usually appeared at the beginning of a new story working alone, behind a desk, in an office. He used new ‘scientific’ gadgets to help him, a conspicuous display of higher education” (573).

Though Rubenstein is correct in asserting that this Santo climbs the social ladder, as he is now educated and distinctively middle class (though in later films he will live in a mansion and drive a snazzy sports car), I want to add that the Santo we see in the comics is a wrestler molded to the trope of the superhero. Like US counterparts, he is an urban hero, uses cutting-edge (though some would argue impossible) technology, and comes to the rescue of the people no matter how small or trivial their affliction may be. He has a distinct identity and persona that separate him from others within the diegesis (though he does not have a secret identity like Superman or Batman—that being said, not all superheroes lead a double life, take for example the X-Men). Like his counterparts, he occupies a social role that is capable of real, powerful change; though not a journalist (Superman, Spiderman), philanthropist (Batman), or scientist (Iron Man, the Hulk), El Santo’s job as a wrestler is deeply powerful within the Mexican context, as the fighter in the ring is not solely there to entertain, but rather to “invoke a series of connections” with deep political ramifications (Levi xiii).

The wrestler, in other words, is not simply a charlatan in a leotard (as the audience knows that the matches are fixed), but rather a public actor within the ring-as-theater paradigm that Heather Levi underlines as so important in considering wrestling within Mexico’s popular and political imaginary. In this line of argumentation, the wrestler is the embodiment or agent of critical ideological dyads within the political and social sphere, responsible for bringing to life abstract and macro processes to a live audience. The wrestler, thus, is a political figure, capable of playing out the theater of real-life within the syntax of the ring. In other words, the Santo of the comics (and then film) “allowed Mexico to find in him a cultural leader” (“permitió que México encontrara en él un líder cultural”; Illescas Nájera 51). In all this, we must also consider that the wrestler transcended the ring, or as Juan Villoro persuasively argues, “the justice meted out by the wrestlers in three rounds without a time limit is too tempting to be corralled within the twelve ropes of the ring” (“la justicia que los luchadores imparten a tres caídas sin límite de tiempo es demasiado tentadora para permanecer entre las doce cuerdas”; 16). In this vein, Levi’s reading of wrestling as performance is expertly parlayed into a discussion of the rise of social wrestlers that never saw the mat of a ring, but who took on important political projects (xii). She includes in this discussion such characters as Superbarrio, Ecologista Universal, Mujer Meravilla, SuperAnimal, SuperGay, and Superniño (128). These characters are evidence of the cultural, political, and social function of the wrestler-type and its configuration as a popular superhero.

El Santo’s meteoric popularity did not simply stop, however, at the comics; he was a television star in lucha libre’s boom during the Alemán presidency, as wrestling was broadcast to a national audience that could now share in the drama of the bouts. Wrestling’s (and El Santo’s) presence on the screen, however, was quickly curtailed by a controversial broadcast ban that saw the sport relegated to specific areas of the country’s growing urban space where an audience could attend a live match. But the television ban was not successful in removing the masked wrestler from the popular imaginary and from ideational constructs of the nation; if anything, it had an opposite effect, as it spurred alternative strategies for producers and media moguls to capitalize on the positive (cultural and affective) asso...