Introduction

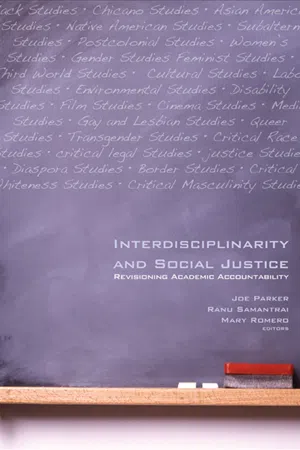

Many interdisciplinary fields exemplify the political ambivalence that characterizes the U.S. academy: ostensibly a critique of that institution's role in reinforcing inequalities, their very existence indicates a belief that the academy may also be an equalizing force in society. Supporters of the ethnic studies, cultural studies, and women's studies programs founded in the late 1960s, for instance, carried their battles from political movements into universities in the faith that changing the production of knowledge would transform social relations, broaden access for the disenfranchised, and thereby change the agents and the consequences of knowledge production. The pattern of scholars and activists joining forces to open fields of research and teaching continued in subsequent decades with the emergence of environmental studies, film and media studies, and gay and lesbian or queer studies. Recent additions—including critical race studies, disability studies, transgender studies, critical legal studies and justice studies, diaspora studies, border studies, and postcolonial studies—take as their epistemological foundation the inherently political nature of all knowledge production, a principle shared by the essays of the present volume.

Through trenchant critiques of disciplinary predecessors, interdisciplinary fields often have defined themselves in contrast with established disciplines. Their attempts to query the conditions and consequences of knowledge production have prompted changes that reach into traditional disciplines and extend beyond the academy to movements for social justice (Bender). For instance, because the staffing needs of innovative programs and evolving disciplines have set in motion institutional changes necessary to accommodate new types of scholars, hitherto disenfranchised groups have gained greater access to sites of knowledge production (Boxer; Feierman; Stanton and Stewart; Messer-Davidow). From literature to sociology and into the physical sciences, scholars are engaging the difficult task of unraveling how assumptions about race, gender, class, colonization, and sexual orientation are embedded in the structure of interdisciplinary as well as disciplinary practices that, in turn, intervene to recreate the world in the image of those assumptions (Shiva; Deloria).

In addition to predictable resistance from practitioners of traditional disciplines, interdisciplinary fields have encountered some institutional, intellectual, and political criticisms from other quarters as well. Even as they have become established features of the academic landscape, they have struggled to maintain their affiliations with social movements (Boxer; Loo, and Mar; Messer-Davidow) and are now frequently subject to criticism from within those movements. Present variations of interdisciplinarity turn a critical eye to the political nature of truth production and to those who claim to be its producers. Their proponents acknowledge that interdisciplinary practices are not innocent of political and epistemological complicity with multiple structures of oppression.1 Moreover, the shift from Enlightenment assumptions and epistemology to postmodern practices has prompted an evaluation of the political and ethical implications of social movements that remain organized around such putatively fixed universals as identity or liberation.

Interdisciplinary fields are no longer provocative newcomers to the U.S. academy. Although their proliferation in some ways is a measure of their success within the academy, the success of their attempts to hold the academy accountable for its claims of promoting the general welfare and contributing to a just society remains an open question. Interdisciplinarity and Social Justice takes this moment in their history to review the effects of interdisciplinary fields on our intellectual and political landscape, to evaluate their ability to deliver their promised social effects, and to consider their future.

Interdisciplinarity: A Contested History

Several influential publications on interdisciplinarity render considerations of politics and social justice secondary or obscure them altogether. Two such books were published early in the formative 1970s following international seminars organized by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): Interdisciplinarity: Problems of Teaching and Research in Universities (Michaud et al.) and Interdisciplinarity and Higher Education (Kocklemans). Two additional influential volumes by Julie Thompson Klein followed in the 1990s (Interdisciplinarity; Crossing Boundaries). Taking such fields as social psychology and biochemistry as prototypical, Klein defines interdisciplinarity as the attempt to synthesize existing disciplinary concepts with the goal of achieving a unity of knowledge for a nonspecialized general education (Interdisciplinarity 12). This apolitical, holistic approach to interdisciplinarity, which we would term multidisciplinarity, is found across the board in the academy from the humanities (Fish) to science research centers (Weingart) to professional associations (Newell).2 But Klein's history largely disregards the social and intellectual challenges to academic orthodoxy and the politics that were the breeding ground for interdisciplinary programs.3 Absent that context, Klein advocates an interdisciplinarity that rejects narrow specialization in favor of an integrative blend of disciplines on the grounds that social needs are best served by the latter's general education approach (Interdisciplinarity 15, 27, 38).

Area studies and development studies offer early examples of an interdisciplinarity that assumes the neutrality of disciplinary truth claims and seeks their integration. But since area studies (including American studies) emerged in the U.S. academy during the early years of the Cold War, any neutrality they claim is belied by their reliance on the category of the nation-state (Brantlinger 27; Shumway) that, in turn, naturalizes colonial territorial boundaries (Chow, “Politics and Pedagogy” 133–34; Kaplan and Grewal 70–72). The divisions suggested by Asian studies and American studies parse difference into manageable and essentialized areas domesticates a global network of contradictory power relations, whereas development studies spin evidence of inequity and injustice into tales of inevitable progress (Sbert; Rafael; Pletsch; Esteva; Escobar).

But against the neutrality of disciplinary knowledge stands an array of scholarship that uncovers the messy history of disciplinary norms linked to social inequalities and entangled in lengthy, highly politicized struggles about authoritative claims to truth (Moran 8; Steinmetz, Politics; Messer-Davidow, Shumway, and Sylvan). Hans Flexner and others note that the emergence of modern notions of disciplinarity in European academies in the nineteenth century coincided with the industrial revolution, agrarian changes, and “the general ‘scientification’ of knowledge” (Flexner 105–06 ctd.; Klein, Interdisciplinarity 21; Moran 5–14). As a consequence, modern education shifted toward specialized teaching based on research configured by the modern disciplines, which in turn was driven by industrial demand for emergent technologies and appropriately trained employees. Lorraine Daston has argued that the traditional European emphasis on liberal humanism as the basis for educational authority was replaced between the 1810s and 1840s in Germany by the research seminar that linked specialized training to emerging professions such as philologist or laboratory scientist, university teacher or industrial chemist (71–72, 77–78). Rather than the philosopher's skillful thought unifying the knowledge practices of advanced education, in the newly configured German university, critical thought was supplanted by the form and values of the seminar itself: diligence, punctuality, performance of written and oral work on schedule, careful attention to minute detail, devotion to technique, and a cult of thoroughness, responsibility, and exactitude (78, 82). The spread of what has come to be known as the German model of the research university throughout Europe and its colonies combined with the attendant proliferation of specialized disciplines and their seminar format for advanced study to produce the modern, seemingly worldwide university.

Joe Moran notes the expanding impact of the physical sciences in the nineteenth century, when they became the measure for all other knowledge and the template for the new fields now known as the social sciences (Moran 5–7; Haskell; Shumway and Messer-Davidow). Following Michel Foucault (Clinic), Michel de Certeau (1984), and Terry Eagleton, James Clifford has argued that from the seventeenth century onward, the natural sciences defined themselves in opposition to the humanities by contrasting their aim of transparent signification with an emphasis on rhetoric (in rhetoric or literature), pressing their claims to facticity against the status of fiction, myth (in literature), or superstition (religion), and practicing objectivity in contrast with subjectivity (Clifford 5). Thus the natural sciences pressed even the humanities to adopt the criteria of evidence and argumentation modeled on modern reason, as exemplified by mathematics in the physical sciences (Moran 7). Indeed, Moran argues that the move towards interdisciplinary study in the humanities challenges precisely the preeminence of science as the predominant model for disciplinary truth claims. Such histories suggest the importance of examining the complicity of the modern research university with the industrialization of modern society, the enclosure of agrarian lands, the emergence of market economies and the modern professions, and attendant questions of exploitation, inequality, and injustice (Flexner; Althusser; Bourdieu).

In Michel Foucault's widely influential account (Discipline; “Subject and Power”), the French Enlightenment provides the backdrop for the formation of modern discipline understood as both bodily discipline and docility and disciplined knowledge forms. Vincent Leitch summarizes a permeation of the social by discipline so detailed and thorough as to produce the modern disciplinary society:

[From] the 1760s to the 1960s—the modern era—societies became increasingly regulated by norms directed at the “docile body” and disseminated through a network of cooperating “disciplinary institutions,” including the judicial, military, educational, workshop, psychiatric, welfare, religions, and prison establishments, all of which entities enforce norms and correct delinquencies. . . . In casting the school as a “disciplinary institution,” Foucault has in mind specifically the use of dozens of so-called disciplines, that is, microtechniques of registration, organization, observation, corrections, and control [such as] examinations, case studies, records, partitions and cells, enclosures, rankings, objectifications, monitoring systems, assessments, hierarchies, norms, tables (such as timetables), and individualizations. The disciplines, invented by the Enlightenment, facilitate the submission of bodies and the extraction from them of useful forces. These small everyday physical mechanisms operate beneath our established egalitarian law as ideals, producing a counter law that subordinates and limits reciprocities [. . . . ] Universities and colleges deploy the micro disciplines to train and discipline the students in preparations not only for jobs and professional disciplines, but for disciplinary societies. (168)

This configuration of educational institutions also accounts for the multiplication of the specialist societies and journals that still remain powerful regulatory and enforcement mechanisms in the Eurocentric academy. Foucault's account has been central to much interdisciplinary work that names the trouble with established disciplines in the Eurocentric university (Brown; Messer-Davidow, Shumway, and Sylvan; Shumway; Said; R. Young).

The competing histories of the justice effects of the modern disciplinary university reviewed here suggest numerous ways to understand the relationship between interdisciplinarity and social justice. The narratives of Flexner, Daston, and Moran indicate that the modern, disciplinary academy limits the audience of academic writing to other specialists in the academy, industry, and government, even as it supplies that audience with evaluative criteria such as originality, viability, and the regulative mechanisms of the research seminar (Daston 79). Against that backdrop, interdisciplinarity may be understood as returning critique to the center of the educational enterprise while changing the social groups that benefit from the educational enterprise. The Foucauldian account also implies that interdisciplinarity can be an intervention into a modern microphysics of power to prepare students not for disciplinary society but for practices that ground social relations outside those defined by the professions and by measures of capitalist productivity.

Justice Through New Objects of Knowledge and New Methods

Within education, interest in social justice increased dramatically in the 1960s and early 1970s as students and faculty on campuses worldwide learned from anticolonial liberation struggles in the global south and linked their language, tactics, and goals to change primary, secondary, and postsecondary education (Ali and Watkins; Katsiaficas; Committee; Editorial Staff; Omatsu). For instance, in their early years, ethnic studies in the United States resulted from broad, cross-racial coalitions demanding third-world liberation for students domestically and overseas (Caute; Naison; Acree; Whitson and Kyles; Wang). As Steven Feierman has shown in an analysis of the discipline of history, decolonization in the global south combined with multiple liberation and civil rights movements in the global north to provoke a major shift in the academy, evidenced by increasing racial, gender, sexual preference, and national diversity of scholars at work in academic institutions and consequent major shifts in historiography. Greater interest in social justice is also seen in a general crisis of epistemology, signaled by dramatically decreased satisfaction with knowledge protocols and with the social effects of academic work (Boxer; Carson; Deloria; Eagleton; Feierman 84–86; Foucault, Archaeology; Guha and Spivak; Miller; Said; Steinmetz, “Decolonizing”; Chakravorty, this volume), or what Levinas has termed “ontological imperialism” (qtd. Feierman 167–68). From the crisis in the credibility of educational institutions emerged a number of interdisciplinary fields that refused disciplinary claims to political neutrality and objectivity, preferring instead to direct their research and teaching openly toward the aims of social justice.4

Through a complex process of negotiated agreements with university leaders and, in the case of public institutions, with state officials (J. Cohen), the fields of study that emerged were generally named in terms of discrete social groups contextualized, as in the case of environmental studies, both as particular objects of knowledge and as agents of change. In the United States, these included fields—such as Black Studies, Chicano studies, and Asian American studies—that rejected disciplines dominated by white faculty and the erasure of non-white objects of knowledge; early women's studies programs that emphasized the study of women as a corrective both to their erasure from the humanities and to the pervasive sexism of the academy and the society (Boxer; Messer-Davidow); and Native American studies that rejected imperialism in the academy. These were accompanied in England by an attention to socioeconomic class that brought the concerns of the working class to the center in the academy (Hall; Williams, Revolution 57–70). And comparable changes were occurring around the globe as students and faculty engaged in social struggles turned their attention to transforming the academy in Tokyo, Mexico City, Lagos, Rio de Janeiro, Cairo, and across western and eastern Europe (Zolov; Ali and Watkins; Caute). The extraordinarily high level of interest in engaging the politics of knowledge production is indicated, for example, by the exponen...