![]()

1

Introduction to My Memoirs

GENERAL GLOBACHEV

I must state that I had absolutely no intention of setting forth a history of the Russian Revolution in making these memoirs available to the public, nor to examine in any broad terms the reasons behind this pernicious event. This is too complex a task at the present time and will be the lot of a future dispassionate historian. I only wanted to present this information, which with other material might serve in the drafting of such a history.

As someone who was close to senior government officials, and by the nature of my work having direct contact with various sectors of the population, I was able to communicate with various people, and to observe and note that which might escape the attention of an ordinary citizen or a person of little experience in internal political affairs. Many minor items have slipped from my memory because years have passed since the time that these events took place, but everything that deals with the characteristics of political figures and the character and meaning of events themselves have remained fresh in my memory. I greatly regret that there is much for which I cannot offer documented evidence, because all records of the Security Bureau, as well as my personal belongings, were either burned, pillaged, or fell into the hands of the new revolutionary authorities during the early days of the riots.

Over a two-year period I was witness to the preparation of the riots against the sovereign power, unstoppable by anyone, bringing Russia to unprecedented shock and destruction. I use the word “riot” and not “revolution” because the Russian populace had not yet “ripened” for revolution and because the masses, in general, did not participate in the overthrow. In fact, what is essential to the very essence of revolution is an idea. If we look at history, we will see that revolutions take place under the influence of some sort of idea taking hold of the breadth of the populace. For the most part, these ideas are patriotic-nationalistic. Was there an idea among the leadership of the Russian Revolution? There was, if we can call ambition and self-interest of the leaders—whose sole purpose was to grab power, at whatever cost—an idea.

Russia was engaged in a colossal war. It would seem that for its successful conclusion it would have been necessary to exert all of its strength, forgetting all of one’s personal interests and bringing everything in sacrifice to the fatherland, remembering that, before all else, it was necessary to win the war, and only afterward to be occupied with domestic matters. Meanwhile what did the cream of the crop of our intelligentsia do? With the very first military misfortune, it tried to undermine the people’s faith in sovereign authority and the government. Not only that, but it tried to lower the prestige of the bearer of sovereign authority in the eyes of the masses, accusing him from a platform of People’s Representatives, now of government betrayal, now of immoral dissolution. The State Duma—the representative organ of the nation—became an agitating tribunal revolutionizing the nation. These People’s Representatives, to whom all of Russia listened, decided without considering the consequences to incite the masses on the eve of the turning point of military fortunes on the front, exclusively for the purpose of satisfying their own ambitions. Was there a patriotic idea here? On the contrary, the essence of all the activities of these people was betrayal of the government. History has no examples of a similar betrayal. All of the activity of the Socialists and Bolsheviks that followed in the dismantling of Russia was only the logical aftermath of the betrayal by those traitors who planned the overthrow, and the last of these is less to blame than the first. They were right in their own way; they wanted to transform the government and the social order in Russia according to their program, which was the ultimate goal of their many years of work and dreams, cherished by every kind of socialist. This was the realization of their ideology.

The Russian intelligentsia should have learned from other governments that were involved in the war, where notwithstanding their difficult ordeals and class struggles, they closed ranks behind their governments and forgot their domestic feuds, and all personal interests were sacrificed for the common good where everything was risked to achieve one cherished goal—defeat of the enemy. Everybody worked in the name of a national idea. In Russia they worked to the advantage of the enemy, trying as much as possible to pull down the army and tear down the powerful monarchy. If the Central Powers presented a united front against Russia, they had an ally among the leaders of the intelligentsia who constituted a united domestic front to besiege our army’s rear. The work of this internal enemy was carried out methodically over a two-year period, taking advantage of every misfortune, every mistake, and every event or occurrence at this time.

Special organizations were created that were supposedly subsidiary governmental agencies whose purpose was the successful conduct of the war, but in reality their intentions were solely to eat away at the government and army from inside. Even in establishments in the capital, they tried to foment discontent and opposition to the established order. Everything was used: false rumors, libel in the newspapers, the tough economic times, influence on the working masses, underground revolutionary movements, discord among government officials, personal intrigues, and other tactics. In short, everything was set in motion to create a revolutionary atmosphere so that there would not be a single defender of the old order once the banner of the revolutionary center was raised. The government, in its weakness, unwittingly played into the hands of its adversary, unable to bring forth a single individual from among its own who could at least be talented and firm in political action and capable of stopping this evil matter. So, the awful Russian revolution began, and its nightmarish consequences continue to this day, and nobody knows when this will end.

The Russian people often rebelled during Russia’s thousand-year history, in each case egged on by traitors who deceived them. Let us recall “The Time of Troubles” and “The Streltsy Uprising,” which were brought about by Boyar sedition, “the Stenka Razin insurrection,” “Pugachev’s Rebellion,” and the Decembrist revolt. In all these instances, traitors to Russia deceived the masses. Relatively recently, in 1902, during the agrarian disturbances in Ukraine, agents of revolutionary committees incited peasants against landowners by spreading false rumors of a supposed royal decree that allowed peasants to take the land and property from landowners—and the peasants believed this. This serves to demonstrate that the Russian people were capable of insurrection, but not revolution. It was the same in the 1917 revolution; the people were deceived by the alleged oncoming famine; they shouted, “Give us bread,” but nobody cried out “down with Nicholas” or “down with the Tsar.” Did Rodzianko or Alekseev inform the Tsar of this? I do not know, but I think not. In addition, if the Tsar had abdicated and someone had been found who was capable of suppressing the February nightmare, nobody would have called it a revolution, but simply an insurrection of the Petrograd garrison.

We could more easily call the events of 1905, after the unfortunate war with Japan, a revolution rather than an uprising. This revolution was caused by extremists who used displeasure with the war’s misfortunes as the foundation of a national idea that the monarchy had lost its prestige as a great power. In the defense of national interests, a new power needed to emerge—a national power capable of restoring Russia’s former greatness and giving the country a new order that would provide a robust national life instead of an incompetent outmoded monarchy. Thus, the revolution of 1905 moved and grew under the banners that were founded on national patriotism.

I will not stick to a chronological order in my memoirs, but I will pause on those events, occurrences, and individuals that stand out as phases in the preparation of the February uprising of 1917, the prior two years, and the subsequent development of the Russian Revolution.

![]()

2

The Globachevs’ Early Years

VLADIMIR G. MARINICH

Konstantin Ivanovich Globachev was born on April 24, 1870. The world was an active place. Alexander II, the Tsar Emperor of Russia, was in his fifteenth year of reign, had initiated major reforms in Russia, and several years earlier had sold Alaska to the United States. Elsewhere, Bismarck had unified the German states into one empire, and Cavour and Garibaldi had unified Italy. Across the Atlantic, Ulysses S. Grant was President of the United States, and the country was in its fifth year of the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War. Konstantin was born in the Ekaterinoslav Province of Russia, where his family had recently been awarded hereditary nobility.

Globachev’s father, Ivan Ivanovich Globachev, was born in the Ekaterinoslav Province in 1835. The major city of that province was Ekaterinoslav, now known as Dnepropetrovsk; then as now it was a major industrial and transportation center on the Dnieper River. Ivan Ivanovich’s career included several years in the army, from which he resigned with the rank of Staff Captain, before entering into a career in police work as a local police superintendent of the Fourth Precinct of the Sokolskii District of the Grodno Province. By 1860 he had become the Chief of Police of the province, a rank equivalent to that of a lieutenant colonel, and who reported directly to the provincial governor.1

In 1869 Ivan Ivanovich was given a significant award. His family name was entered into the registry of hereditary nobility. This type of award did not bestow property or title to the recipient, but it did raise the family socially and helped to open doors of education and job positions to the family. Ivan Ivanovich died in 1876 at the age of forty-one as a result of an infection that developed in his foot. Konstantin was six years old when his father died and, throughout his life, Konstantin disliked the scent of hyacinths because it reminded him of his father’s funeral.

FIGURE 2.1. Konstantin Globachev, about ten years old. Marinich collection.

Konstantin had two brothers, Nicholas and Vladimir. Vladimir was the oldest of the three. Nicholas was next, and Konstantin was the youngest. Their mother remarried a man whose last name was Axenov, who had two or three sons by a previous marriage. One of these sons was named Leonid, and he became a physician.

Konstantin attended secondary school at the Polotz Cadet Corps and then the First Military Academy of Paul. He graduated in 1890 and was commissioned as a junior lieutenant in the Keksholm Life Guards Regiment, which was stationed in Warsaw. Warsaw was a major city, and since the eastern part of Poland was part of the Russian Empire, Russian regiments were stationed throughout. Globachev’s higher education continued in the General Staff Academy of Nicholas in St. Petersburg, after which he returned to his regiment. His two brothers were also officers in the Keksholm Regiment, and all three were known throughout the regiment as Vladimir “the happy Globachev” (веселый Глобачев), Nicholas, “the talkative Globachev” (болтливый Глобачев), and Konstantin “the handsome Globachev” (красивый Глобачев). The two older brothers continued in military careers. Vladimir became a colonel and a Politzmeister (police chief) of a district in Petrograd. He died in Finland after the Revolution. Nicholas attained the rank of major general and was commander of the Novogeorgievsk Fortress during World War I. He was arrested in Russia after World War II and died in Siberia.

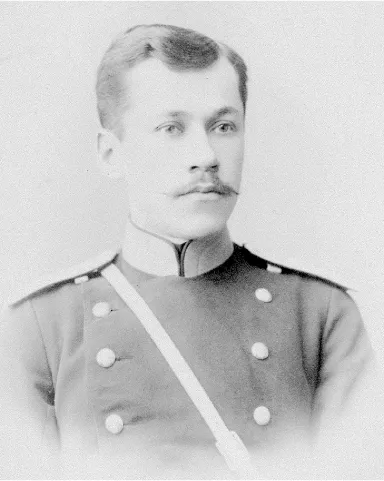

FIGURE 2.2. Globachev as a Junior Lieutenant. Marinich collection.

FIGURE 2.3. Nikolai Korneleevich Popov. Marinich collection.

It was during his regimental tour of duty in Warsaw that Konstantin met and married Sofia Nikolaevna Popova. Sofia Nikolaevna Popova was born in Warsaw in 1875. She was the daughter of Nikolai Korneleevich Popov, who was a Councilor of State for Peasant Affairs (Destvitelnyi Statskii Sovetnik).

Sofia’s parents may have died when she and her siblings were not yet adults. Sofia’s daughter Lydia stated that a guardian raised Sofia and her brothers and sisters. Sofia had three brothers and two sisters. The brothers were Michael, Nicholas, and Vladimir, and the sisters were Olga and Maria. They all received a good education. Sofia became fluent in French, German, and Polish, in addition to her first language, Russian. She was also an excellent piano player. Sofia and Globachev met in Warsaw and were married there on January 9, 1898. He was twenty-seven years old, and she was twenty-two. They had three children: Sergei, who was born around 1900 and died around 1902 or 1903 from typhoid fever; Lydia, who was born October 21, 1901, and Nicholas, born in 1903.

FIGURE 2.4. Sofia, circa 1898. Marinich collection.

FIGURE 2.5. The newlywed Globachevs, 1898. Marinich collection.

Sofia’s brother, Nicholas, was a colonel and regimental commander of the Brest Infantry Regiment during World War I, and had seen action in the Russo-Japanese War. Following the 1917 Revolution, Nicholas and his family became separated, and he wound up either in Latvia or Lithuania. The night before he was to be reunited with his wife and daughters, Tamara and Alla, he died of a heart attack.

Sofia’s brother Michael was in the army and served most of his caree...