![]()

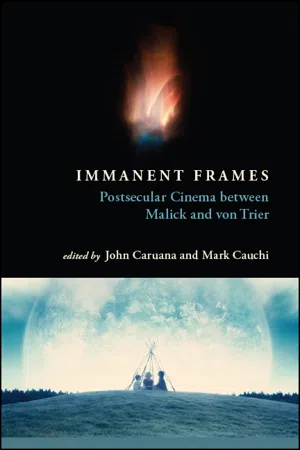

Part I

The Poles of

Postsecular Cinema

Malick and von Trier

![]()

1

ROBERT SINNERBRINK

Two Ways through Life

Postsecular Visions in Melancholia

and The Tree of Life

RELEASED COINCIDENTALLY WITHIN the same year, Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011) and Lars von Trier’s Melancholia (2011) offer contrasting cinematic and metaphysical meditations on the apocalyptic theme of the “end of the world.” At first glance the two filmmakers could not appear more opposed: publicity-shy Malick, reclusive auteur who shuns Hollywood and global festival circuits, and attention-seeking von Trier, whose notorious persona, controversial remarks, and Festival performances have earned him as many detractors as admirers. Despite such superficial differences, their recent films display striking correspondences, unexpected affinities, and revealing contrasts. Both films examine a postsecular vision of modernity in which the Enlightenment ideals of progress, scientific mastery, and possessive individualism have lost much of their credibility and motivating power. Both also offer striking image-sequences expressing a poetic disclosure of worlds and an experience of aesthetic-moral sublimity. In this sense, both films are performative demonstrations of the aesthetic and ethical possibilities of cinema in an age of pervasive skepticism, moral restlessness, and ethico-political uncertainty.

On the one hand, the depiction of and response to the “end of time,” which both films offer, could not appear more different: von Trier’s resolutely tragic vision of an ethical acknowledgment of finitude as the only “rational” aesthetic and moral response to imminent (environmental and social) catastrophe stands in stark contrast with Malick’s redemptive vision of spiritual reconciliation through love in the face of an incipient nihilism and loss of meaning in contemporary American (and Western) society. On the other, this apparent opposition belies these films’ fascinating exploration of transcendence and immanence, understood as metaphysical-ethical perspectives on the value and significance of existence. Viewed together, both films reveal a complex dialectical relationship between transcendence and immanence despite their apparent opposition.

This chapter will explore these contrasting postsecular visions—the one exploring a redemptive vision of love and aesthetically mediated spiritualization, the other adopting a tragic stance, mediated via an aesthetics of sublimity that refuses metaphysical or spiritual comfort. I will suggest that both films can be regarded as confronting, and responding ethically to, the cultural-historical experience of nihilism. As such, both films may also be understood as contrasting, yet complementary case studies in a cinematic ethics elaborated by aesthetic means.

Transcendence and Immanence: The Tree of Life and Melancholia

Apart from their narrative explorations of the apocalyptic “end of the world” theme, there are a number of philosophical and ethical concerns that bring together Melancholia and The Tree of Life. One is the question of an immanent (this-worldly) versus a transcendent (other-worldly) conception of the value of human existence: that is, whether the source or origin of meaning and value in our finite temporal experience is to be sought in an earthly or a supramundane sphere, one that either remains within or supersedes the bounds of experience; and whether the very concept of an “end of the world,” even one explored through cinema, demands either an immanent or a transcendent ethical response to the prospect of such an “end.” Another is the question of nihilism and how cinema might respond to it. Nihilism is understood here as the cultural-historical, but also metaphysical-moral experience of what Nietzsche called the “devaluation of all values”: the loss or withdrawal of authoritative sources of meaning or value in the world, the undermining of received foundations of morality, ethics, or cultural meaning, coupled with the acceptance of triviality, absurdity, or meaninglessness as underlying our everyday experience in modernity. Both films, I suggest, deal with these philosophical questions in distinctively cinematic ways; ways that adopt what appear to be opposing, but on deeper reflection prove to be interrelated, aesthetic, and ethical stances—immanent versus transcendent—toward the sources of value or meaning defining our contemporary horizons of experience.

The Way of Transcendence: The Tree of Life

One of the most challenging questions raised by Malick’s The Tree of Life is how to deal with its overtly religious, theological, and spiritual themes. Indeed, I would suggest that it is precisely The Tree of Life’s “Christianity” that lies at the heart of the film’s polarized reception. There are, I suggest, at least three narrative/mythic dimensions of The Tree of Life—the familial melodrama, the historical-spiritual Fall or loss of the American Dream, and the cosmological creation myth combining spiritualism and naturalism—all of which are woven together in the story of the O’Brien family.

All three dimensions coexist and communicate with each other in a topology that could be called mythopoetic (combining myth and poetry). The first layer is the familial melodrama, which centers on middle-aged architect Jack O’Brien’s [Sean Penn] spiritual-existential crisis on the anniversary of his younger brother’s death (killed when he was 19). Set during the course of this one day, a troubled and lost O’Brien recollects, via a complex use of flashbacks, the lost life and joy of his childhood, growing up with his two brothers, stern father [Brad Pitt] and serene mother [Jessica Chastain] in Waco, Texas, during the 1950s. The second layer is the historical-spiritual story, the way the O’Brien family’s story depicts—through visual style, mise en scène, framing, composition, and use of light—a mythic Fall from the romanticized historical “Eden” of the 1950s Midwest to the spiritually destitute space of contemporary urban America, marked by the imposing, geometrically ordered glass and steel architecture of downtown Houston. The third layer is the cosmological creation myth, interpolated within the familial melodrama and historical “Fall,” which evokes the sublime emergence of life within a re-enchanted universe imbued with aesthetic grandeur and spiritual wonder. This third story culminates in an eschatological myth (Jack’s transcendent vision of the destruction of the world at the “end of time”), which brings together the familial melodrama, the story of the Fall, and the mythic-spiritual quest in an overwhelming experience of spiritual reconciliation through love.

The question of the film’s Christianity and its religiosity has created consternation among critics: those interpreting the film from (and as bound by) a secular perspective (in which the question of religion is not thematic or else is treated critically), and those interpreting it from (and as expressing) a postsecular perspective (in which the question of religion is made explicitly thematic or endorsed by the film). One of the most telling aspects of this clash concerns the differing interpretative strategies that critics have deployed in order to deal with (or else avoid) the film’s Christianity/religiosity. There are four that a survey of the film’s critical reception reveals: (1) uncritical affirmation of the film because of its religious content (the “Christian” interpretation of the film); (2) uncritical rejection of the film for essentially the same reason (the anti-religious response); (3) disavowal of the film’s religious content in favor of its aesthetic merits (the “aestheticist” or secularist reading); (4) acknowledgment of the film’s aesthetic merits and transformation of its religious content into generic or postsecular forms of spirituality (the “revisionist” or postsecular approach). In any event, whether one either criticizes the film’s alleged aesthetic vices as a way of rejecting its religiosity, or downplays its religiosity and praises the film’s aesthetic virtues, the two aspects are inextricably entwined (as evident, for example, in the pointed use of voiceover in the film). Moreover, it is hermeneutically implausible to simply ignore or dismiss these theological-religious elements, as some critics seek to do, while at the same time claiming to offer a critical reading or interpretation of the film. The Tree of Life’s religiosity therefore poses a problem, not only for evaluating the aesthetic response to the film but for understanding the relationship between film, philosophy, and religion more generally.

David Sterritt (2011), for example, praises the film as a “stunning achievement,” an ambitious, personal film evoking “a sense of divine wonder by artfully juxtaposing an autobiographical bildungsroman with sublime artefacts chosen from the artistic and cultural treasures” gleaned from the long history of Judeo-Christian thought. Nonetheless, he criticizes what he takes to be Malick’s theological position: the film’s shift from philosophy to theodicy, “arguing for God’s goodness despite the evidence of a fallen, iniquitous world,” which thereby removes, he claims, the human dimension of pain, struggle, and suffering (Sterritt 2011, 57).

Other approaches acknowledge the theological-religious dimensions but find ways of relativizing them such that they no longer need to be taken into account as independent aspects of the film. Moritz Pfeifer (2011), for example, has articulated the hermeneutic antinomy that The Tree of Life seems to generate by contrasting religious-idealist and analytic-modernist perspectives on the film. On the one hand, there is the idealist, for whom The Tree of Life is an ineffable aesthetic and emotional revelation, showing beauty and reality in ways that evoke spiritual truth. On the other, there is the analyst, for whom the film should be analyzed and understood as a self-reflexive historical meditation on memory and childhood experience, mediated by cinema and popular cultural imagery (the glass coffin image from Disney’s Snow White, for example, or the 1950s fascination with space, science, and the universe). From this point of view, any spiritual or religious meaning to be gleaned from the film is relativized: either mediated via the perspective of the various characters, or else referencing, more or less ironically, other cinematic works (Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Tarkovsky’s Mirror, for example).

Another alternative is to take the film as a religious work of art, an approach favored by many Christian viewers and critics, some of whom point to Malick’s own avowed religious faith as providing explicit evidence of authorial intention. A good example of this “religious reading” is offered by Christopher Barnett (2013), who treats The Tree of Life as a theological-religious work of art, drawing on Malick’s explicit references to the Book of Job and Christian theology, as well as the cinematic aesthetics of wind/breath as indirect figurations of spirit/ruach/pneuma. Exploring the use of wind imagery in Malick’s films, Barnett points out that the use of wind or breath as a way of figuring spirit or the presence of spirituality in nature and the world puts Malick’s nature imagery within a long cultural and historical tradition of religious symbolism. The focus and emphasis on images of wind or breath in many important sequences within Malick films, and notably within The Tree of Life, lend support to the idea of Malick’s celebrated naturalism and poetics of natural beauty as having a spiritual-religious significance within the framework of a Christian theology of spirit understood as ruach or pneuma. Moreover, the power of Malick’s cinematography (or rather that of his collaborator, Emmanuel Lubezki) along with his pointed use of music combines a commitment to aesthetic realism and material expressivism with an exploration of implicit spiritual ...