![]()

PART ONE

REPRESSION

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Control, Exclusion, and Play in Today's Future City

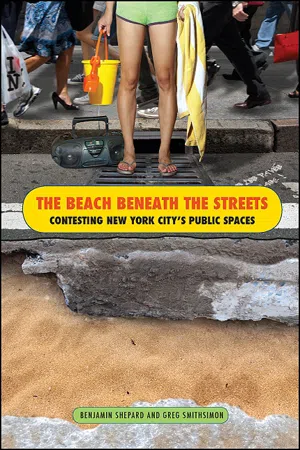

The title for our work—The Beach Beneath the Streets—refers to the French May '68 slogan. “Sous les pavés, la plage!” often translated as “Beneath the pavement—the beach!” The anonymous graffiti from Paris 1968 conjures up any number of images—a subaltern vitality, the control of something unruly, the dominance of nature, and a possible return of the repressed. The expression also speaks to a new kind of social imagination, a right to view the city as a space for democratic possibilities, a social geography of freedom. “All power to the imagination,” is perhaps the most famous bit of street graffiti from 1968. Throughout the period, the Situationists, a highly influential French avant-garde group who took part in the street demonstrations, argued urban space created room for one to consider and conceive of new perspectives on the very nature of social reality. Within such a politics, the rules of everyday life would be turned upside down and restored into a “realm for play” (Vaneigeem 1994, 131).

The Situationist response to the privatization of public space included innovations in approaches to activism. Two primary tactics utilized by the Situationists included interventions termed “détournement” and “dérive.” Détournement refers to the rearrangement of popular signs to create new meanings (Thompson 2004). “An existing space may outlive its original purpose … which determines its forms, functions, and structures; it may thus in a sense become vacant, and susceptible of being diverted, reappropriated and put to a use quite different from its initial one,” French Marxist philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre would explain. He described the way the process changed a local produce market in 1969. “The urban centre, designed to facilitate the distribution of food, was transformed into a gathering-place and a scene of permanent festival—in short, into a centre of play rather than of work—for the youth of Paris” (LeFebvre 1974, 167). Dérive refers to short meandering walks designed to resist the work- and control-oriented patterns of Georges Haussmanns redesign of Paris (Thompson 2004). This approach anticipated today's Critical Mass bike rides—a current “best practice” in playful, prefigurative community organizing. “The dérive acted as something of a model for the ‘playful creation’ of all human relationships,” writes theorist Sadie Plant (1992, 59). The point of dérive is active engagement between self and space. It changes the way one sees the streets (60). Such forms of play reveal a sense of agency, of control of the way one wants to participate within the world. While play takes place in all human cultures, its roots in movement activity can be found in the works of the Surrealists and Dadaists (Plant 1992). The Situationists built on this trajectory, which in turn found its way into modern movements ranging from queer direct action ACT UP zaps to Reclaim the Streets (RTS) and Pink Silver style tactical frivolity of the street parties of today's global justice movement (Jordan 1998; Shepard 2009; Shepard 2011).

“The city is burning tonight (Sous les pavés, la plage!)” Photo by view-askew, mural by Seth Tobocman, Norway.

Dérive and détournement also highlight something important about public space and its relation to the social imagination, the topic of this book. Public space is a source of contestation. It is intricately associated with any number of notions: democracy, public debate, Shakespeare's “all the worlds a stage,” Elizabethan theatre, comedy, and tragedy. Such thinking finds its way into the very geography of the public commons. Take the town of Arakoulos, just a few kilometers east of Delphi, the ancient home of the mythical oracle. Today streets still ring with their own chorus. On summer evenings, chairs are set out ten and twelve deep in front of the cafes that line the only significant street in town. They overflow with occupants. Outside, the chairs and conversations of all the cafés intermingle in a daily social ritual that goes on for hours. The agoras in the center of the ancient city states of Greece have long been presented as the absolute ideal of public space. Coupled with the equally engaged and lively use of public space in a Greek town like Arakoulos, the moment is inspiring for a student of public spaces. But it quickly fills an American observer with the simple question: how come streets in the United States no longer feel like this?

The comparison is misleading. The United States does have vibrant, diverse public spaces. There is no single ideal type of public space, yet the bucolic Mission Dolores Park overlooking downtown San Francisco confirms that there are vibrant examples here as well. In this compressed, urban park only a couple blocks long, there is marvelous integration of different users of the space, but simultaneously firm self-segregation as well. On any given day, one might find in the park twenty-four hour drug dealing down the hill from male sunbathers, kids on the unenclosed playground next to dogs running off their leashes, cops in their squad cars across the field, a political rally next to a basketball game—picnickers, tennis players, people waiting for the trolley, and even the anarchist direct action group Food Not Bombs serving free meals. The park seems like just the kind of space William H. Whyte would linger over as an ideal space of diverse, self-regulating interaction. Yet, the integration of these different uses hinges on a degree of self regulation: chaos would erupt if any of these groups infringed on the space of any of the others.

The segregation is not all voluntary: people have been assaulted for crossing into the drug dealers' space, disputes erupt between parents and dog owners, cops roar down the walkways. The risk of danger is real, as is exclusivity even in this most ideal of public spaces. Public space, even at its best, is a complex balance. And while advocates of public space often are strong opponents of police surveillance or corporate control, the space described here could not exist without order and social control. But control is not emanating from the squad car. Order in public space is generated primarily, though not exclusively in this case, by users. Despite the priority of self-regulation in public space, police increasingly play a role in filtering, controlling, and segregating access to public space. Competing liberatory and controlling visions of public space run throughout this book.

Though these opening vignettes offer glimpses of the recreational possibilities of such spaces, the purpose of the book is serious. Public space has attracted wide ranging attention from far-flung perspectives and disciplines; it is claimed like a battlefield, mourned as a dying species, embraced as the very incubator of democracy. Work coming out of these varied concerns is all valuable, but very difficult to rectify with each other. Three factors are considered here: exclusion, control, and play. In their own ways, each highlights the central features of public space, its repression and resistance, and provides the means by which students of public space can think coherently about the different traditions of the study of public space. Juxtaposing control and resistance, one locates a dialectic in the most passionate examinations of public space—comprised of alarms sounded at the privatization of public space, even the impending death of public space, and celebrations of the singular liberatory potential of the politics of public space. As opposition to privatized space becomes more sophisticated, and activists' interest in the potential of public space becomes more widespread, both the defense of public space and the strategic value of public space benefits from a framework with which to understand the ongoing threats to the future of public space. This book seeks to provide a framework that can relate insights about recent elite domination of public space as well as breakthroughs in the strategic use of public space for emancipatory purposes.

While the opening examples (as well as a few to follow) come from different sides of the globe, this examination of public space centers on New York. That is useful in part because the politics of space are strongly influenced by elites who seek to shape space and direct its uses—large-scale real estate developers, politicians, and bankers capable of moving large amounts of capital into and out of a region or project. Part of what makes New York an intriguing global city is the way that transnational social and cultural capital infuses its neighborhoods with a distinct glocal—global and local—dimension. Developers hold positions of particular influence in New York City and its politics, making this a particularly productive place to examine spatial trends that are nonetheless influential elsewhere. Thus, while public space takes shape in a local physical geography, the capital behind the bricks and mortar is connected to a neoliberal economic project aimed at the privatization and commodification of countless aspects of life, from water to air to the lands of cities around the world (Klein 2003). When New York faced a fiscal crisis in the mid-1970s, its reorganization served as a kind of trial run for the impact of these neoliberal policies on local space. In the years since, New Yorkers have had to contend with one crisis after another, with various camps promoting policy solutions involving still more privatization. Much of the work of New York activists, radicals, revolutionaries, queers, and community organizers has been a response to the threats borne of the 1975 restructuring. Given this, a brief review of New York City history since its fiscal crisis is instructive.

The Transformation of New York City in Power and Space

The transformation of space that this book examines parallels transformations in capitalism. For some time, authors who monitor the accessibility of public space have linked the loss of public space to the more aggressive turn in capitalism beginning around the early 1970s as the postwar consensus was stagnated by inflation and then replaced by a more ruthlessly profit-seeking global capitalism (Zukin 1991; Sorkin 1992; Davis 1990; Castells 1989; Sassen 2001). That global change had particular manifestations in individual cities, and New York's have been well-documented (Fitch 1993; Abu-Lughod 1999). As capitalists privatized public commons, eliminated programs guaranteeing public welfare, and launched vengeful raids on working class prosperity, elites first backed away from the city, then returned to disemboweled democratic spaces—building within their gentrified, eviscerated shells either elite playgrounds, upper-middle class consumerist shopping festival marketplaces, or “bread and circus” distractions from the economic restructuring going on all around.1

Recently, several important works have delved into the last forty years of New York history to consider the story of its vexing transformation. While Vitale (2008) considered the change in terms of policing, and Fitch (1993) viewed them via real estate, Freeman (2000) and Moody (2007) considered the city's changes from the vantage point of labor relations and shrinkage of the public sector, and Greenberg (2008) considered how New York was rebranded after the crisis. Zukin (2010) examined how the soul of the city has been threatened as the city is redeveloped on the foundation of a commodifiable, gentrified culture. And Marshall Berman (1982; 2007) considered what New York tells us about modernism. Berman, of course, was not the first to view the city as a narrative for our age. “Here I was in New York, city of rose and fantasy, of capitalist automotion, its streets a triumph of cubism, its moral philosophy that of the dollar,” Leon Trotsky wrote in his autobiography. “More than any city in the world, it is the fullest expression of our modern age” (quoted in Moody). Implicit is a recognition of the cultural and economic influence of a distinct urban space. Over the past four decades, a transnational, neoliberal revolution in financing, policing, and real estate has shifted the way the city lives, works, and understands itself. Our view of the city begins with a glimpse of the space from the street to the sidewalk, between commerce and pleasure, at the intersection of work and play.

A common thread running through the writing about New York is the flux in public space and by extension the public sector. Here, one is invited to consider the ways the city is organized to preserve, privatize, profit from—sometimes support, and even defend public spaces. Borrowing from this rich tradition of scholarship, we consider changes in the urban environment via its public spaces, the work located within them, the ways people play, build communities, and make lives for themselves here. Much of the recent changes in New York's public spaces originate from the profound economic and demographic dislocation of deindustrialization. New York's deindustrialization really began with the post war era. Years before globalization, technological advances, including containerization, robbed New York's waterfront of some thirty thousand jobs from the 1950s to the 1970s (Freeman 1990; Levinson 2008). In 1966, the Brooklyn Naval Yard closed, robbing the city of some sixty thousand jobs (Freeman 2000). In the years to follow, many of these workers found employment at Kennedy Airport, as New York become more and more connected to the world. The shift was significant. “Changes in the waterfront divorced the city from its past,” wrote labor historian Joshua Freeman (1990, 164). As ships increasingly docked in New Jersey, sailors stopped even coming to the city to work, linger, or loiter, leaving the city without a presence dating back to the earliest settlements in the city. “By the 1970s, much of New York's glorious waterfront lay abandoned,” Freeman continued. “Decaying piers on Manhattan's West Side routinely burnt up in spectacular fires. Some docks were used as parking lots, others as bus barns and sanitation department garages. A few served as impromptu sunbathing decks” (164–65). Chapter 4 of this work considers the ways a different set of communities reoccupied abandoned piers on Manhattan's West Side.

Still, people continued to come to New York in search of industrial work. Throughout this period, a “generation of blacks and Latins were conscientiously following the American immigrant model—just when the American immigrant–industrial city was crumbling,” Marshall Berman (2007, 17) notes. The new arrivals sometimes had difficulty finding jobs or bank loans to support their neighborhoods. Redlining increased, furthering a capital crisis draining resources from neighborhoods inhabited by minorities (Wilder 2000). Streets and buildings in the Bronx began to disintegrate in front of the world's eyes.

By the early 1970s, the post war business-labor accord, in which business agreed to compensate workers in exchange for labor stability, began to crumble. And the fiscal crisis witnessed a rebellion against the city's social democratic polis. “If we don't take action now, we will soon see our own demise,” a New York financier confessed during a closed door meeting of business executives in 1973. “We will evolve into another social democracy” (quoted in Moody 2007, 17). Fearing New York City was becoming a European model welfare state with budgets and entitlements too generous for their liking, New York's bankers, business elite, and Governor Rockefeller pulled the plug, turned right, and sketched a path for the city's neoliberal rebirth. To pull off their coup, New York's business elite built on a series of financial crises.

In the years after 1968 and more intensely after 1972, a well-connected elite comprised of a triumvirate of America's social upper classes, corporate communities, and policy formation organizations called for a shift in direction for US social pol...