Masako N. Racel

Historians today no longer teach world history as simply a collection of regional histories, but now attempt to present history as an integrated whole that allows students to see beyond the confinement of national, regional, or even continental boundaries. I can best describe this fairly recent concept with an analogy. History is like a massive piece of cloth that spreads out to the horizons. When we look at it closely, we see that the cloth is composed of myriad individual threads that combine with each other to form an ever-tightening weave. This weave binds together the individual threads to form the tapestry of human interaction. The rich colors of various cultural, religious, and social characteristics are apparent in the fabric, but we can only observe the true pattern by stepping back and viewing the whole from a distance. The world history survey is where we are able to provide that wide perspective.

Departmental needs determine how many professors organize their courses. Most college-level survey courses are supposed to serve two major objectives. First, they provide freshman non-history students with the essentials of cultural literacy in world history. In this role, faculty must provide students with a basic understanding of history, so it is easier to cover broad topics and concepts without getting bogged down in details and minutiae. Second, such courses must also serve as introductions for those seeking to take upper division history courses, which are typically organized by regional, chorological, and/or thematic basis, such as “Medieval Europe,” “China before 1600,” “Mughal India,” etc.; and require a much more detailed knowledge of specific regions, people, and events. This juxtaposition of needing to keep the course focused on the overreaching concepts of history, while also providing the necessary details for those wanting a deeper and more specialized understanding creates a challenge for most instructors, especially when you consider that no one is an expert on all time periods and regions. My personal approach in addressing this problem has been to combine both the regional and world history approaches by first offering a big picture, followed by regional histories, and then weaving the regional histories together using the larger concepts of a world history approach. With this in mind, the Silk Roads and other trade routes in Eurasia offer an excellent way to organize world history lessons for the period before 1500.

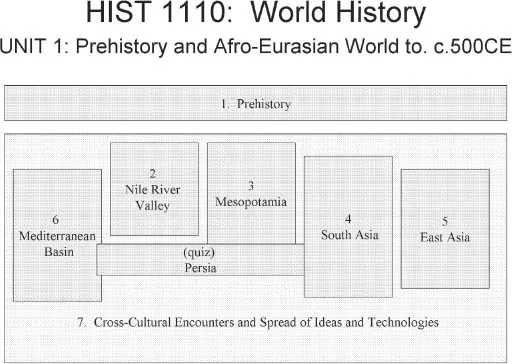

At Kennesaw State University, all students are required to take a one-semester world history course that covers everything from prehistory to the present. Since this is only a one-semester, three-credit course that meets twice a week for sixteen weeks, there is certainly a huge restraint on time that I can spend on each lesson. With such a short course that covers all of human existence, clear organization is the key for students to categorize and comprehend the major points of world history. To that end, I have divided the course into three units or epochs. The first two units focus on Afro-Eurasian History (commonly known as the Old World), while the third unit deals with the era of global integration whereby the so-called New World becomes a major part of world history. The first unit covers the time period from prehistory to circa 500 CE. The second unit explores the time period following the collapse of the classical civilizations (Roman Empire, Han Dynasty of China, etc.) and before the age of global integration (c. 1500). The third unit closes out the course with everything from the age of exploration (with a discussion of American civilization) to the present. I incorporate the three major eras of the Silk Roads into the first two units of the course.

Silk Roads: Three Eras

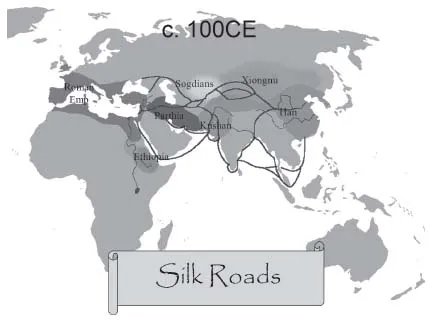

Even though we commonly use the singular form “the Silk Road,” the term generally refers to the collection of Eurasian roads and trade routes that connected the Mediterranean Basin in the west to China in the east. Some would apply the term Silk Roads, to refer not only to the overland route that traveled through the oasis cities of Eurasia, but also the northern steppe routes and various sea lanes. The original travelers along the Silk Road did not know it by that name; German explorer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen coined the term much later in the nineteenth century. Although silk was probably among the most important commodities, and perhaps the only product that actually traveled the entire length of the roads, other goods, such as spices, glassware, medicinal plants, and musical instruments were also traded via the Silk Roads.1

It is hard to identify exactly when the Silk Roads came into existence, but it is relatively easy to identify high points in their history. The first major era for the history of the Silk Roads was during the period in which the Roman Empire to the west and the Han empire to the east both flourished. These two empires did not connect directly, but a series of overlapping trade circuits ultimately linked the two empires together indirectly. The second great age came about with the emergence of the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates on one hand, and the reunification of China under the Sui and Tang dynasties on the other end of Eurasia. The third great age began with the creation of the Mongol empire that encompassed much of the Eurasian landmass during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. For the first time, the land routes of Eurasia were controlled by a single government, providing a mechanism to facilitate trade and travel across all of Eurasia.2 With the spread of the plague in the fourteenth century, the decline of the Mongol empire, and the opening of new ocean trade routes in the 1500s, the importance of the Silk Roads generally declined.

First Great Era of the Silk Road Trade

The first unit establishes the foundation of world history by covering the time period from prehistory to circa 500 CE, the epoch often referred to as the ancient and classical periods. A few of the major issues I address in this unit are the Neolithic Revolution and the emergence and development of complex societies in Afro-Eurasia. After covering several specific regional societies (Nile River Valley, Mesopotamia, South Asia, East Asia and the Mediterranean Basin), I add one lesson entitled “Cross-Cultural Encounters and the Spread of Ideas and Technologies” in order to pull together the different regions of Afro-Eurasia, and to better incorporate the importance of the Silk Roads during the classical era.

This lesson introduces some of the essential concepts of world history, such as the importance of cross-cultural encounters as agents of change, while providing the context in which such encounters and exchanges may take place. I explain the general pattern of change, where new ideas and/or technology may be first adopted, and then adapted to fit the needs and tastes of a certain locality. As a part of process of adaptation, I also introduce the term “syncretism,” in which new “foreign” ideas are combined with old indigenous ideas, resulting in new blended ideas and concepts. I also discuss the tendency for large, stable empires to create conditions favorable to trade here, leading to the eventual development of the Silk Roads that connected the Han empire in the east to the Roman Empire in the west.

This era corresponds well with the traditional Chinese accounts of the opening of the Silk Roads when Emperor Han Wudi sent Zhang Qian (Chang-ch’ien) to the “western territory” in 139 BCE, in order to make an alliance with a nomadic people from Central Asia that the Chinese referred to as the Yuezhi (Yueh-chih). At the same time, the demand for silk garments was very high among Roman elites. Greeks and Romans had known of silk since at least the fourth century BCE, and following the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE when the Parthians startled the Roman soldiers with their silk banners, silk grew in popularity. Despite various attempts to limit its use to the aristocracy there was a healthy demand for trade that allowed the Silk Roads to flourish while these two great empires served as anchor points on opposing ends.3 With the decline and eventual collapses of both the Han and Roman empires into smaller and less stable regionally based kingdoms, the Silk Roads’ importance faded as trade slowed to only a trickle.4

I introduce general patterns of long distance trade; with nomadic peoples, such as the Xiongnu and the Sogdians, playing the critical role as middlemen. These middlemen never traveled all the way from China to the Eastern Mediterranean and vice versa, but instead only traveled particular sections of the Silk Roads that they were familiar with, trading with similar people, ultimately connecting one end of Eurasia to another. I mention the popularity of the silk among Roman elites, but also include other goods that traveled the Silk Roads. The importance of domesticated animals, such as camels, donkeys, and horses for trades, as well as the dangers travelers faced from banditry, dehydration, and sandstorms can also be included in this section.

Centering the discussion on the Silk Roads offers many opportunities to introduce important world history concepts that a regional history approach would otherwise overlook.5 The Silk Roads were not only important for the exchange of goods; they also served as a conduit for the transmission of ideas. Buddhism flourished along the Silk Roads, as the famous Dunhuang caves and statues of the colossal Buddhas of Bamiyan attest. The case study of the spread of Nestorian Christianity along the Silk Roads, in particular, serves as an excellent way to show how a heterodox sect could survive official condemnation by spreading into areas where religious authorities were unable to impose restrictions. The case of Manichaeism, which emerged in third-century CE Mesopotamia, then part of Persian empire, offers a great example of syncretism in which elements from Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and Buddhism all merged together to form a new religion.6 Not all transmissions along the Silk Roads were beneficial: travelers also transmitted diseases. We can link the outbreak of plagues in both the Roman Empire and the Han empires during the second and third centuries to the Silk Roads.7 The disintegration of the Han and Roman empires, due in part to epidemic disease, resulted in a general decline of the Silk Road trade which did not fully revive until the seventh and eighth centuries CE.

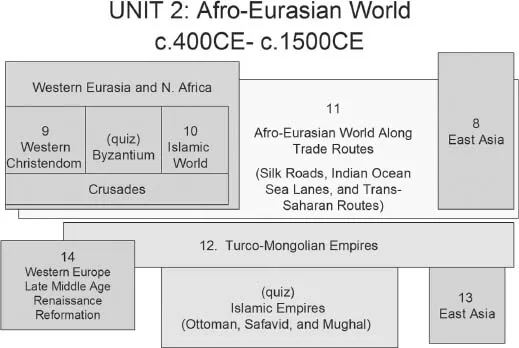

The Second Era: The Societies along Three Trade Routes

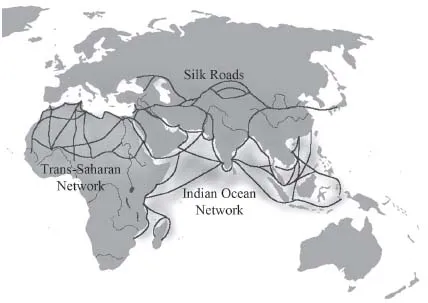

My second unit covers the period between c.500 and c.1500 CE, which I divide roughly into the time period before and after the emergence of the Mongol empire. For coverage of pre-Mongolian Afro-Eurasia, I still use a regional and thematic history approach for lessons on East Asia, Western and Eastern Europe, and the Islamic world (I group the last three together as “Western Eurasia and North Africa” and focus on the transition from a Mediterranean-based society that splits into Western and Eastern Christendom, and Dar-al-Islam). I integrate regional and thematic histories with a lecture on the three trade routes of Afro-Eurasia, including the Silk Roads (overland), the Indian Ocean trade network and the trans-Saharan trade network. By organizing the lesson along these trade routes, I can easily incorporate areas that a regional history approach might neglect, such as Southeast Asia. Furthermore, this approach allows me to address important world history issues, such as the existence of “world” economic systems in premodern eras.

I intentionally insert this lesson after covering Imperial China (the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties) and the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates since these two areas became the new anchor points of the Silk Roads on both ends of Eurasia, much like the Han and Roman empires during the earlier era. A purely regional approach tends to overlook the fact that these two regions were thriving simultaneously and at one point were adjacent to each other. China, after approximately four hundred years of division, was reunited under the short-lived Sui Dynasty (581–618) and pivotal Tang Dynasty (618–907). The Islamic empire experienced phenomenal growth after its founding c. 622 and quickly unified a vast region stretching all the way from the Indus River valley to the Iberian Peninsula. The Battle of Talas River in 751 CE, during which the newly established Abbasid Caliphate and the Tang empire clashed over a territorial dispute, clearly demonstrates the contact between the two cultures. Not only was the Battle of Talas River important as a military confrontation, it also deserves the credit for the introduction of paper-making technology into the Islamic world, since some of the Chinese captured there were skilled paper-making artisans.

The period of the High Caliphate (c. 661–945) was a time of intercontinental contact and cooperation when the transmission of ideas and technology spread throughout the Islamic World. Historians normally attribute this astonishing spread of culture and ideas to the fact that the early Islamic empires controlled a vast territory that included the Indus River Valley, Persia, the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa, and the Iberian Peninsula. Islam’s teaching about the hajj, which encouraged its followers to visit the holy city of Mecca at least once in their lifetimes, created favorable conditions for intercultural encounters and exchanges since people from the farthest regions all traveled to a central location, bringing with them different cultures and ideas.8 Dar-al-Islam (the abode of Islam) served as a conduit for knowledge and technology. The Arabs adopted and adapted the numerical system developed in the Indus River valley, which we know as arabic numerals. At the other end of the empire, the Muslims also learned of Greek scholars and translated ancient Greek works into Arabic. Such developments within the Islamic world eventually traveled back to Western Europe via the direct contact that resulted from the Crusades of the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. While most world history texts mention the impact of Islam on Western Europe, they often overlook the fact that much of the overland Silk Road that ran through Persia, and east to central Asia, also fell under the control of Islamic empires. As a result, nomadic pastoralists and merchants in the surrounding regions, such as the Turks and Sogdians, adopted Islam, adding to its international character. The revival of Silk Road trade thus helped the spread of Islam.

The conversion of the nomads along the Silk Roads also contributed to the cosmopolitanism of Tang China. This period is noteworthy since it is the time when famous Chinese monk Xuanzang traveled to India and bought back Buddhist scriptures, using the Silk Roads.9 Unlike the allegedly more insular China of later periods, the Tang era was exceptionally open to foreign people and cultures. Muslims began establishing communities within China around c. 650 CE. Famous stoneware figurines from the Tang era, such as those depicting camels and Central Asians, provide clear evidence of China’s connection with the Silk Roads. An Lushan, who set off a famous rebellion, was a Turkic-Sogdian general from the frontier guard. Such individuals are indicative of the multiethnic character of the Tang era that resulted from the flourishing trade along the Silk Roads.

In addition to the overland Silk Roads, the sea lanes of the Indian Ocean were prosperous at this time. Organizing a lesson along the Indian Ocean network is an excellent way to break away from the normal regional or continental models. Southeast Asia, which most textbooks tend to neglect, is easy to incorporate as a part of the Indian Ocean Trade network. Since this network included Swahili cities of East Africa, teachers can avoid a continental perspective that tends to isolate Africa from the rest of the world. Although the Indian Ocean approach can separate the coastal regions from the rest of Africa, it is possible to avoid this problem by showing the connection between the Swahili city-states and the inland economy, the most notable example of which was the rise of the Monomopata empire during the fifteenth century. Additionally, I show the interconnectedness of world trade, since the cowrie shells many African societies used for currency came from the Maldives Islands in the Indian Ocean. While I have students thinking outside of the box, I include a discussion of the Austronesian migration, which resulted in populating parts of Southeast Asia, the Pacific (including Hawaii and Easter Island) and even Madagascar, which is usually treated as part of Africa.

I am also able to incorporate the trans-Saharan routes into my lecture about societies existing along trade routes. I explain the rise of empires along the Sahalian belt, such as Ghana, Mali, and Songhay, in connection with the rise of the trans-Saharan trade. This is a great opportunity to break free from the myth that Africa was an isolated continent by demonstrating sub-Saharan Africa’s connection to the Islamic world as well as Europe. The introduction of Islam into West Africa is another major theme for this section. Indeed, all three trade routes—the Silk Roads, the Indian Ocean trade network and the trans-Saharan trade routes—offer ways to explain the spread of Islam through trade. In my opinion, this is one of the most important factors contributing to the spread of Islam. This section offers an opportunity to debunk the myths of forced conversion to Islam that many students seem to subscribe to. It also provides an excellent opportunity to talk about the patterns of “social conversion” Jerry Bentley discusses in Old World Encounters, where the conversion of urban elites precedes conversion of the masses.10

The Third Era: The Mongols

The almost-complete unification of the Eurasian landmass under the Mongol empire marks a distinct stage in the history of the Silk Roads. Never before the emergence of the Mongol empire had a single political entity controlled the Silk Roads. The period of Pax Mongolica (Mongolian Peace), the thirteenth century, was marked by the unprecedented ease of travel across Eurasia. According to Marco Polo, there were supply stations throughout the empire that would provide lodging, horses, and other supplies for travelers:

You must know that the city of Khanbalik is a centre from which many roads radiate to many provinces, one to each, and every road bears the name of the province to which it runs. The whole system is admirably contrived. When one of the Great Khan’s messengers sets out along any of these roads, he has only to go twenty-five miles and there he finds a posting station…. At every post the messengers find a spacious and palatial hostelry for thei...