eBook - ePub

Fashion Talks

Undressing the Power of Style

This is a test

- 273 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fashion Talks

Undressing the Power of Style

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Fashion Talks is a vibrant look at the politics of everyday style. Shira Tarrant and Marjorie Jolles bring together essays that cover topics such as lifestyle Lolitas, Hollywood baby bumps, haute couture hijab, gender fluidity, steampunk, and stripper shoes, and engage readers with accessible and thoughtful analyses of real-world issues. This collection explores whether style can shift the limiting boundaries of race, class, gender, and sexuality, while avoiding the traps with which it attempts to rein us in. Fashion Talks will appeal to cultural critics, industry insiders, mainstream readers, and academic experts who are curious about the role fashion plays in the struggles over identity, power, and the status quo.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Fashion Talks by Shira Tarrant, Marjorie Jolles, Shira Tarrant, Marjorie Jolles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Dressing the Body

The Politics of Gender and Sexuality

Chapter 1

Fashioning a Feminist Style, Or, How I Learned to Dress from Reading Feminist Theory

The suit was gold and black, a shiny, iridescent weave that caught the light. It achieved the greatest of thrift store miracles: its skirt and jacket had together survived their long journey, from the department store where they had originally been purchased in the early 1960s, to the give-away bag where they ended up a decade or two later, to the used clothing bins where they were sorted, to the rack at my local vintage store where I had snatched them up. What first caught my eye was the jacket. It bore a striking resemblance to the one Madonna wore in Desperately Seeking Susan—the one that she eventually traded for a pair of boots and that Rosanna Arquette's “Roberta” bought in order to emulate Madonna's “Susan.” It was the summer of 1985, and I had just seen the film and was in love with all things Madonna. I already owned a wrist full of black rubber bracelets, knee-length black leggings, and pointy-toed, black flat boots just like the ones Madonna wore in the “Lucky Star” video. Now I would have my very own Desperately Seeking Susan jacket, just in time for my departure for New York where I was about to start college.

Throughout college my Madonna obsession remained intact, but my style went through some changes. The gold-and-black vintage suit was now worn with 1950s-style prescription glasses, as I modeled myself after a character from an old Perry Mason rerun to create what I dubbed my “court stenographer” look. Later, the suit moved to the back of my closet, and a faded Black Sabbath T-shirt would be worn—ironically, of course, as I was no heavy metal fan—with rolled-up jeans and combat boots. When graduation day finally came, I wore a flowered, vintage shift dress with heavy men's shoes, the toes of which were filled with toilet paper in order make them fit. And of course I wore a lot of black, the look of all Sarah Lawrence students in the 1980s.

I tell this story because my introduction to feminist theory was both literally and symbolically connected to fashion, and this connection has also shaped my development as a feminist theorist. As an undergraduate, I explored feminist ideas with the same approach that I took to scrounging in thrift stores: discover something, try it out, see if it fit, and if it did, make it a part of my style. I tried on Marxist feminism, psychoanalytic feminism, and Mary Daly. Some theories suited other people more than me, some fit well, and some were just uncomfortable. The writings of the Redstockings and other radical feminist groups of the late 1960s and early 1970s were a perfect fit: I loved the bold, daring, and outrageous language of their manifestoes.

The fashion of the women who wrote these feminist works also captivated me. Looking at photos from the 1968 Miss America protest, it wasn't just the words on their demonstration signs that caught my eye: Look at those great dresses! That necklace is amazing! I wish I had a pair of sandals like that! These were hip feminists, women who were definitely in on the joke as they paraded a crowned sheep down the Atlantic City boardwalk to “parody the way the contestants (all women) are appraised and judged like animals at a county fair.”1 They were protesting the confines of traditional femininity, but they were doing it with flair and with great outfits. I admired them for their style—both in politics and in clothes.

Andrea Dworkin best represents how feminist ideas and fashion came together to shape my feminist identity and how they intertwine to pose important theoretical questions. When I discovered Dworkin's work in college, I quickly read everything by her that I could get my hands on. She seduced me with her over-the-top rhetoric and her unmitigated view of gender relations. I remember sitting in my dorm room reading Intercourse, her 1987 book about, well, sexual intercourse, in which she describes heterosexual intercourse as a fundamental part of male domination of women: “intercourse distorts and ultimately destroys any potential human equality between men and women by turning women into objects and men into exploiters.”2 Her language was combative and direct, offering no room for exceptions. “[G] etting fucked and being owned are inseparably the same.” “[M]ost men have controlling power over what they call their women—the women they fuck. The power is predetermined by gender, by being male.”3 As a young feminist trying to develop my own writing voice, my own style of expression, I found Dworkin's certainty and confidence compelling.

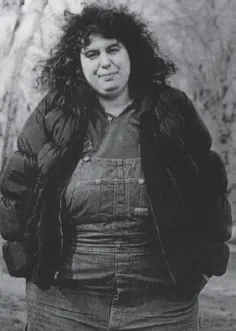

Shortly after this discovery, I saw a picture of Andrea Dworkin. She was fat and did nothing to disguise this fact. Wearing her trademark overalls and with hair that looked like it hadn't been brushed in a while, she exemplified a certain kind of feminist style that, like her writing, seemed to say, “I don't give a fuck what you think of me.” Her defiantly un-coiffed image corresponded to her ideas on femininity, first articulated in Woman Hating, in which she writes: “Plucking the eyebrows, shaving under the arms, wearing a girdle, learning to walk in high-heeled shoes, having one's nose fixed, straightening or curling one's hair—these things hurt. The pain, of course, teaches an important lesson: no price is too great, no process too repulsive, no operation too painful for the woman who would be beautiful.”4 The cost of femininity, the cost of beauty, was pain, and here was a woman who said, “I'm not going to be part of this system.”

As Ariel Levy writes, “When most people think of Andrea Dworkin, they think of two things: overalls and the idea that all sex is rape.”5 As a college student, I already wondered about the relationship between these two things, the overalls and the ideas, and since then I am increasingly convinced of the connections and conflicts between clothes and feminist theory. In her 2002 autobiography, Heartbreak: The Political Memoir of a Feminist Militant, Dworkin only mentions her signature style once, in the preface, when she writes: “So here's the deal as I see it: I am ambitious—God knows, not for the money; in most respects but not all I am honorable; and I wear overalls: kill the bitch.”6 While her memoir chronicles her life from childhood, it contains no further details as to what made her decide to wear—apparently almost every day—this particular clothing item. Yet in the brief, prefatory self-portrait, overalls are mentioned with ambition and honor: central to how she defines herself (“the deal as I see it”) and to the opposition she faces, whether real or imagined (“kill the bitch”). Designed to protect one's shirt from dirt, overalls are a particularly utilitarian form of clothing, an item not usually associated with either ambition or honor. Were the overalls meant to downplay her ambition, to signal that she wasn't in it “for the money”?7 Overalls were also originally designed for men, and unlike other styles of pants they seem deliberately asexual, disguising the body behind their denim. Were Dworkin's overalls meant to indicate that she had successfully stepped outside of what Sandra Bartky terms the “fashion-beauty complex,” with its required vigilant self-monitoring of female bodies and appearance?8 Thinking back to what first captivated me about Dworkin's writing, I find Dworkin's fashion choice is as much a rejection of social norms of “women's wear” as her writing is a rejection of liberal pleas for equality. But her flippant aside about wearing overalls suggests that clothes nonetheless express something important about a theorist, even one who critiques the social conventions of feminine style.

Image 1.1. Andrea Dworkin.

As an undergraduate, I went through my Dworkin phase—I even had a pair of overalls—but ultimately neither her rhetorical nor her fashion style stuck with me. The overalls, I concluded, were horribly unflattering; they had a way of making me (or anyone) look shapeless, and the style made me feel like a kid. Overalls looked good on little children and on Andrea Dworkin, but not on me. I still preferred vintage women's clothing, with its evocation of the glamorous (if prefeminist) good-old-days when people never left the house without being “dressed.” Dworkin's arguments also lost their sway. Her view of penetrative sex bore little relationship to my own experience; her view of men as inherently different from women made little sense to me. And then there was her writing style with all of its unqualified arguments. (“Strong writing but repetitive argument,” my undergraduate self wrote on the inside cover of Right-Wing Women.) What had originally captivated me now troubled me. I found myself seeking other types of feminist theories: ones that could ask complicated questions without providing easy answers; ones that could express ambiguities, contradictions, and a lack of certainty; ones that could address female pleasure as well as female oppression. And, yes, ones that would take note of the significance of clothing.

In fact, the case of Andrea Dworkin points to a fundamental divide within feminist thought since its inception: whether to focus on women's oppression and lack of power or whether to focus on women's agency and potential.9 As one scholar notes in summing up this divide:

On the one hand, feminism is about the oppression of women. Women are not treated fairly in the world, and feminism attempts to remedy that: feminism thus necessarily speaks of women's misfortune. If women were not disadvantaged and disempowered, there would be no need for feminism. On the other hand, feminism is about women's potential. If feminism could envision only women's lack of power, it would be a recipe for hopelessness rather than a dream that energizes us to change our lives and make the world better for women. Thus, feminism must speak of women's possibilities. If women were always and everywhere completely downtrodden, there would never have been any feminism. This is the double foundation of feminism.10

As Dworkin's work illustrates, this debate has been most visible in feminist theorizing on sexuality, articulated as a divide between the dangers and pleasures of sexuality.11 One position argues that sexuality is dangerous for women: central to the maintenance of female oppression, a site of coercive power over their lives, and filled with violence and bodily harm. Another asserts that sexuality is pleasurable for women: central to definitions of self-hood, a site of human connection and joy, and a venue by which to exert agency and self-expression.

While the pleasures and dangers of fashion may have lower stakes than those of sexuality, the feminist debates around fashion are constructed around similar questions of women's agency and autonomy. Many feminists have argued that fashion is a means of controlling women and keeping them trapped in a feminine, and thus subservient, position in relation to men.12 This view is already expressed in 1949 when Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex writes that for a woman: “The purpose of the fashions to which she is enslaved is not to reveal her as an independent individual, but rather to cut her off from her transcendence in order to offer her as prey to male desires.”13 Beauvoir's critique was repeated by the second-wave feminists who came after her a generation later. In her 1984 book Femininity, for example, author-activist Susan Brownmiller describes feminine fashion as central to maintaining gender difference and thus female oppression. As she writes, “To the Western mind the grouping of men in trousers and women in skirts is something akin to a natural order, as basic to the covenant of masculine/feminine difference as the short hair/long hair proposition.” She adds, “I suppose it is asking too much of women to give up their chief outward expression of the feminine difference, their continuing reassurance to men and to themselves that a male is a male because a female dresses and looks and acts like another sort of creature.”14 Throughout her discussion of clothes, Brownmiller makes a strong case that when women wear trousers they are challenging the gender binary, obscuring the differences between men and women and thus, according to her argument, lessening the oppression of women.15 Women wearing pants, it would seem, is central to eliminating sexism. Thus, as Brownmiller puts it, in the 1970s “it became a feminist statement to wear pants.”16

Brownmiller's argument in favor of pants recalls Dworkin's justification for overalls and shows that the clothing we deem “unisex”—and thus gender neutral—has traditionally come out of men's wardrobes. For all intents and purposes, when we say androgynous clothing we mean male clothing, even though the common definition of androgynous is something “neither distinguishably masculine nor feminine.”17 In other words, when a woman dresses “like a man” she becomes androgynous, but when a man dresses “like a woman” he becomes feminine. Men's clothing worn by women thus symbolizes a rejection of femininity on two levels: as its masculine opposite and as its “gender-free” alternative. When some second-wave feminists “argued that it was necessary to reject feminine fashion by ad...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Feminism Confronts Fashion

- I. Dressing the Body: The Politics of Gender and Sexuality

- II. Fashion Choices: The Ethics of Consumption, Production, and Style

- About the Authors