![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Toward a Genealogy of Black Queer Spirituality

This project began as a search for James Baldwin’s literary progeny. In my graduate studies of African American literature, Baldwin’s name inevitably surfaced in any discussion of homosexuality because his debut novel, Go Tell It On the Mountain (1953), is transitional in the canon in that it places same-sex desire squarely within black religious experience, and also because of the overt depictions of (sometimes interracial) bisexual and homosexual behaviors throughout his oeuvre. According to the lore, Baldwin, the self-proclaimed “disturber of the peace,” blazed a new trail when he infused religious elements into portrayals of (homo) sexual ecstasy. Well, I wondered, who followed him? Baldwin scholarship notwithstanding, critical investigations into this specific trope are scarce. So this somewhat genealogical project grew from the following questions: Who since Baldwin has written about the ways black LGBT people think of themselves in relation to notions of the sacred, God, and the afterlife? To what ends do other fiction writers attempt to disentangle (or further delineate) the knotty dilemma of the black, sexually queer, Christian-identified subject? In what ways do black writers who identify as queer, lesbian, gay, or bisexual attend to the intersection of spirituality and same-sex eros? The first answer I found was that Baldwin is not the patriarch I believed him to be.

Richard Bruce Nugent belongs at the beginning of this genealogy for two significant reasons. First, he is important to a discussion about homoeroticism in the African American literature because his lyrical, experimental narrative, “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade” (1926), is credited as the first expression of overt black male homosexuality in the canon. Second, the 1970 publication of Nugent’s short story, “These Discordant Bells,” in the NAACP publication, Crisis, connects him directly to the black queer spiritual tradition introduced by this book. The story originated within a series he called “Bible Stories,” which, as a unit, appropriates the gospels of the Christian bible (narratives surrounding the birth, life, and death of Jesus) in order to imagine the homoerotic possibilities in Jesus’ ministry. Because Nugent’s stories briefly include a single black character, I do not analyze his work in the main chapters of this book. This makes his legacy is no less important. Thus, I take some time to expound a bit here on how he participates in the tradition.

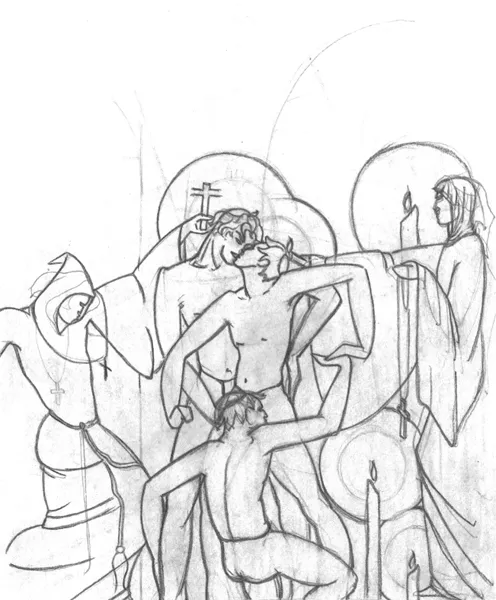

Nugent, a painter, sketch artist, poet, short story author, dancer, and novelist, was born in 1906 into a light-skinned, or “blue-veined,” socially elite African American family in Washington D.C. Although he was not secretive about his sexual affinity for men in his private life or in his writing, Nugent published poetry, artwork, and short stories under the pseudonym “Richard Bruce” to protect his family’s reputation within their social circle. “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,” his best known work, was published as part of an artistic rebellion undertaken with his closest friends and collaborators at the time, which included Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Zora Neale Hurston, and Wallace Thurman. They were the self-named “Niggerati,” the young, emergent intellectual and creative voices of the 1920s who were avowedly determined to resist the conservative politics of representation, called the New Negro ideology, espoused by the well-connected older generation of intellectuals, namely W.E.B. Du Bois, James Weldon Johnson, and Alain Locke.1 Although he was among like-minded artists in the Niggerati, according to his contemporaries, Nugent stood out as the “most colorful and sensational member” (Perry, qtd in Nugent 19) of the cohort. His effeminate mannerisms and openness about same-sex attractions in his work made him a problematic representative of the race. Additionally, the themes of multiracial identity, nudity, and erotic sexuality figure prominently in his visual art and writing. These artistic choices placed him outside the New Negro ideology’s narrowly defined blackness—well, these choices plus his affinity for certain European aesthetics2—and cost him publication opportunities and, for a while, his rightful place in history.3 Eventually, Thomas Wirth, Nugent’s literary executor, would recuperate Nugent’s legacy in published essays, and by creating a website dedicated to his life and work, and through the 2002 publication of Nugent’s “lost” manuscript, Gentleman Jigger, a roman á clef based on his experiences during the Harlem Renaissance. Nugent’s novel provides an alternative narrative to Wallace Thurman’s Infants of the Spring (1932) and Langston Hughes’ memoir, The Big Sea (1940), in its depiction of upper class Harlemites who “live sexually on the sharply transgressive edge of their culture” (Rampersad,“Foreword” ix). Wirth also edited Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance: The Collected Works of Richard Bruce Nugent, which was published in 2005. The sketch “Orgy Under the Cross” (Figure 1) and the remaining extant “Bible Stories” are published for the first time in it.

The short story that establishes Nugent as a contributor to the literary epistemology of black queer spirituality is the first story in the series, “Beyond Where the Star Stood Still,” which provides the premise and context for subsequent stories. In it, Nugent infuses homoerotic attraction into the biblical tale of the magi, alternately known as the “three wise men” and the “three kings,” which travel to bestow on the newborn Jesus gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. One of the magi, King Casper, an Ethiopian, is the sole black character in the series. He absconds with King Herod’s “most beautiful and most beloved” catamite, Carus, after the boy reveals Herod’s murderous intent toward the newborn Jesus. Their relationship is the focus of the second story in the series, “The Now Discordant Song of Bells,” in which King Caspar attempts to instruct the young boy in theological matters. Carus seizes the opportunity to express his homoerotic attraction and romantic desire through philosophical word-play. When King Caspar asserts, “God is love,” Carus signifies by inverting the words and thus expanding the axiom’s meaning to include his desires:

[Carus:] “Ah, true. Love is God.”

Caspar turned his head to view the boy before saying, “Thou hast not heard me.”

And Carus, desiring to see the full lips move more and reveal the great blunt teeth, argued, “but thou thyself hath said, Love is God.”

And Caspar answered, “No, Carus. That God is love.”

“And yet, Caspar, I can only understand that it is as I have said. If one is the other, is not the other the one?

“[…] Thou art allowing thy words to use thee, Carus.”

And Carus had desire to note the contrast his [white] hand would offer on Caspar’s ebony one, but, sitting still and childly, continued saying, “But only that thou mayest know, Caspar, that thou awakes God in me.”

“I awaken God in thee?” Caspar raised himself to his elbow and gazed at the lad, for there was that in Carus’ voice that he did not understand. He questioned, “Thou meanest, I awaken love?”

Carus concealed his excitement at the unconscious awakening in Caspar’s voice, shown in its tone rather than in the question. And Carus replied as simply as before, “Is it not as thou art teaching me, Caspar?”

And Caspar answered, “Thou must not make little of my sayings, Carus, when I speak with seriousness to thee.” Carus was pleased with the look in Caspar’s eye and the unknowing entreaty in his voice. For Carus had seen like signs before and did not know that Caspar was in truth a simple man. So he was bold beneath his childly innocence as he asked, “Is it light speech to say I love thee?” And Caspar, in his earnest zeal, placed a hand over Carus’ hand where it lay on the sand, and his speech was impetuous, “But see thou, Carus, the love of which thou speakest is an active thing, and that of which I teach thee is a name.” (127–128, italics added)

Carus is not a passive student; his insistence that he “can only understand that it is as I have said” is an outright refusal to limit the interpretive possibilities of the meanings of love and God. Essentially, Carus argues for a spiritual principle, which means the feeling of love is a supreme state of being or that love is the reigning emotion. He filters the teacher’s message through the lens of his lived truth and offers it back to the king as a testimony: “Where there is love, there is God.” Thusly, he transforms a cornerstone theological principle into a romantic confession and an interpretation of the divine energies that connect and draw humans to each other. His irreverent inversion, “Love is God,” subverts the conformist limitations of the dominant paradigm; yet, it neither rejects Casper’s God nor refuses Carus’s own sense of self.4 In this way, the exchange is a blueprint for homoerotic spirituality. Nugent’s contributions to black queer spirituality can also be seen in his drawings; artifacts that are featured in Gay Rebel but are beyond the scope of this book.5

Although what I have produced in this book is, ultimately, a claim to a thematic kinship instead of an historical or genealogical analysis proper, the main chapters serve as the answers to the research questions I posed regarding LGBTQ spirituality in literature (the reasons for a limited focus on novels and short stories are stated in the Preface). Also, in the concluding chapter, I list additional texts that fit into this classification. So at this point I must shift the emphasis from the artistic production of homoerotic spirituality to the interrogatory and interventionist discourses which constitute the critical community that presages and facilitates the work I do here. Let us now look toward a genealogy of black queer studies in religion and spirituality.

Figure 1. Sketch, “Orgy Under the Cross,” by Richard Bruce Nugent, date unknown. Used with permission of the Nugent estate.

Before the appearance of Gay Rebel, Nugent’s historic contributions were acknowledged in a brief overview of his life by Charles Michael Smith, titled “Bruce Nugent: Bohemian of the Harlem Renaissance,” in the groundbreaking collection, edited by Joseph Beam, In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology. In the Life appeared in 1986 and is now a time capsule of artistic and critical voices of black men-loving men in the era of AIDS.6 Many of its contributors were not only responding to the absence of black representation in what was becoming a renaissance of gay male literature; some also used the opportunity to give voice to the emotional pain inflicted by black institutional ambivalence and, in many cases, those institutions’ outright refusal to engage in compassionate outreach during the crucial, deadly height of the 1980s AIDS crisis. As the decade progressed, dominant discourses about the transmission of HIV became increasingly hysterical and condemning of those people who contracted AIDS, the so-called gay disease.7 Beam’s In the Life provides testimony of the alienation many were experiencing as black gay people in a white supremacist homophobic society.

It also delivers an important intervention into African American religious discourses in a compelling essay by Pastor James Tinney, entitled “Why a Black Gay Church?” Tinney forged a black gay-inclusive church movement when he was excommunicated from the Church of God in Christ denomination after hosting a revival for gays and lesbians that was endorsing in its tone. That experience, while painful, catapulted him onto a path of restoration, not of his individual faith to his sexuality, but one that aimed to restore his idea of the role of church to its gay believers. He founded the Faith Temple, a nondenominational fundamentalist church, in Washington D.C. Faith Temple defined itself as a culturally black sanctuary for homosexual Christians based on the following separatist principles laid out by Tinney in the essay (I consider this approach a type of restorative separatism, in the vein of Alice Walker):8

The development of Black gay churches will make it possible for Black gay Christians, for the first time, to hear the gospel in their own language of the Spirit, respond to the gospel in their own ways, and reinterpret the gospel in their own cultural context—taking into account both race and sexual orientation at every step in this process. In a socio-political sense, this is called contextualization; in a psychological and existential sense, this is called authenticity; and in a biblical sense, this is called conversion. Whatever it is called, however, it refers to the full liberation of the total Black Gay Christian. (76, my italics)

Tinney argues that full liberation is made possible through reinterpretation and, throughout the essay, emphasizes the need to remain “truly and unquestionably Christian” through adherence to the essence of doctrine (77). In response to the mainstream forces that seek to silence or convert gay people into sexual conformists, Tinney advocates for a queer(ed) space in which a black+homosexual+Christian theology can be enacted “every step.” Through this process, he imagines that the gays and straights of his denomination could reunite as equals under God. Reverend Tinney embodies what it can mean to be in the life and in the spirit and, although he died from AIDS-related health complications in 1988, his gay-affirming convictions continue to take shape in many communities.9

In the follow-up to In the Life, an anthology titled Brother to Brother: New Writing by Black Gay Men (1991) features the classic essay by Charles Nero, “Toward a Black Gay Aesthetic: Signifying in Contemporary Black Gay Literature.” Nero assesses the heterosexism and homophobia in the most celebrated works of the African American literary canon (notably, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Tar Baby, and The Bluest Eye), and reveals how gay writers produce fictional works that revise, critique, or otherwise respond to normative representations of the black experience, including family life, marriage, slavery, and religion. In the section titled “Signifying on the Church,” he points out ways Larry Duplechan’s novel, Blackbird, signifies on Reverend Tinney’s revelation that he had undergone an exorcism before being excommunicated. Nero finds that by imaginatively expanding Tinney’s narrative, “Duplechan exposes an unholy alliance … [in which] the church is willing to oppress its gay people to prove its worth to the middle classes” (306). Significantly, Nero’s essay and, generally, the series of black gay anthologies announce the existence of a black gay aesthetic propelled by visibility politics; that is, a belief in the power of literature to “render their lives visible and, therefore, valid” (290)—a politics, which, historically, has propelled much of African American cultural production.

The critical framework of this book is a fusion of theoretical and cultural perspectives and sexual discourses, namely those wrought by feminism/womanism, African American literary theory, queer theory, and lesbian/gay studies (individual texts are cited in the relevant chapters).10 However, as a study that makes a case for understanding African American religious thought and spiritual expression as part of the ongoing struggle for sociopolitical freedom and, specifically, when I assert that a certain text constructs a “liberation theology,” the arguments I make rely on a theoretical paradigm wrought from, and which is inherently conversant with, rhetorics of Black Theology. This is an important connection to make because Black Theology is a discrete subsection of the religious studies field and one that, until recently, has not been overtly connected to discourses in lesbian/gay studies or fiction studies. It has been, however, always connected to African American literature. The earliest work in this field was guided by a political investment in proving that black American Christian religi...