![]()

1

Setting the Context

There is no power for change greater than a community discovering what it cares about.

—Margaret J. Wheatley

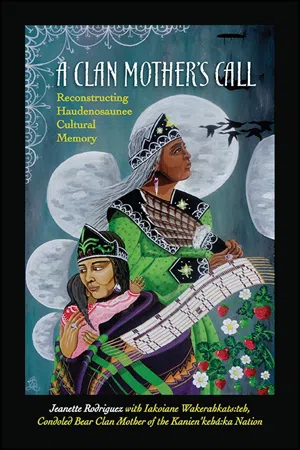

The title of this book is a deliberate double entendre. It refers at once to Clan Mother’s sense of calling, that is, to her life experience, her “spiritual journey” toward self-discovery and assuming her role as Clan Mother. It also refers to the call that Clan Mother extends to her people, that is, to her own voice and to the content of her teaching. Since in so many ways Clan Mother is what she teaches and teaches what she is, my text integrates relevant biographical material in tandem with the narratives and rituals that Clan Mother shares and presides over. My hope is that her biography and teachings will continually illuminate each other, much as they did in the real-life encounters that produced the material for this book. This is the format in which the Clan Mother herself was most comfortable.

This chapter provides the context out of which this research was conducted. First, it considers issues related to culture. While the chapter includes discussion of the methodology that I integrated in producing the book, it secondarily focuses on how Bear Clan Mother seeks to retrieve, reclaim, and reconstruct the cultural memory of her people.

The reproduction of cultural survival is both a biological and an ideological construction. Research in collective memory and historical identity recognizes that critical to obtaining one’s cultural identity and assuming survival are language, ceremonial practices, and the maintenance of principles regarding everyday life. One element that continually emerges in the rebuilding of a people is the need to maintain and transmit the language that carries their intimate and complex worldview. I was moved by Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh’s remarks on this subject:

The vision to lead our youth into a place of wellness through a regeneration of our culture could not be met with incredible reward if it did not embrace our own language. Kaniekeh:ha, my native language, a gift from my mother who did not speak English, showered me in the sweet melody of a mother tongue in my growing years. Native language, in its purest form, is the key to open the celestial door to ancestral knowledge as we begin to help our young in a monumental crossover as they journey to seek the meaning of their lives.

In my book Cultural Memory: Resistance, Faith and Identity, coauthored with cultural anthropologist Dr. Ted Fortier, we constructed a theoretical framework for engaging cultural memory. Our intent was to explore this phenomenon by isolating and analyzing the content, transmission, and sources of empowerment. This included the selection and passage of memories from generation to generation. We examined the construct of this theoretical framework by looking at elements of cultural memory as evidenced within different communities, and through doing so identified six distinct elements of cultural memory: identity, reconstruction, enculturation, transmission, obligations, and reflexivity.

Our intent was not to undertake a definitive, comparative analysis, but rather to explore the ways in which these practices sustained collective beliefs, maintained cultural distinctiveness, and stimulated dignity and defiance in the face of injustice. Now, at Bear Clan Mother’s invitation, and with her collaboration, I will utilize the fruits of that research on understanding cultural memory in order to elevate the voice of a contemporary Clan Mother (Kanien’kehá:ka) of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), who seeks to retrieve, reclaim, and transmit the cultural memory of her people. Native American scholar José Barreiro offers us a detailed description of the duties of Clan Mothers:

She must perpetuate the ways of our people; she must be able to teach the ways of our people to the young people. She must be able to look out for large amounts of people because now, all of the clan people are family. And so, because of the changing of the times, in these days we don’t necessarily have the eldest women being Bear Clan Mother of certain clans, but the eldest eligible woman. We cannot have someone teaching our children our traditional ways who does not follow the traditional ways themselves and cannot perpetuate this way. Some have followed a foreign way, maybe they have become Christianized, or maybe they are following, let’s say the government of another country, the United States. They cannot be truly one of our people because once a person begins following another way of thinking, their thoughts cannot be pure and clean anymore, totally for the people, for the good of perpetuating the traditions which are so important among our people.

The power of cultural memory rests in the conscious decision to choose particular memories and to give those memories precedents within communal memories. Literature review, archival work, and oral history will all be important pieces for this work, for how we remember the past has a profound impact on our actions and the way by which we lead our lives, as well as how we relate to other communities.

It is important to incorporate a number of methods in this kind of work. The principle method I ground myself in is what Eduardo Duran defines as liberation discourse. That is, speaking in a voice that is decolonized or at least in a process of being decolonized, “allowing the once-colonized to reinvent themselves in a manner that is within their control.” Clan Mother Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh prefers to contend that her people are reindigenizing themselves, and in fact the Haudenosaunee “never surrendered to the colonizer.” Researchers tell us that systems of recovery and the promotion of indigenous knowledge are important processes in decolonizing indigenous nations.

Recovering and maintaining indigenous world views, philosophies, and ways of knowing and applying those teachings in a contemporary context represents a web of liberation strategies indigenous people can employ to disentangle themselves from the oppressive control of colonizing state governments.

Numerous scholars in multiple fields (e.g., theology, anthropology, history, politics, etc.) have explored the effects of the conquest on indigenous people. In addition to deaths caused by warfare, forced labor, brutality, and subjugation, many native people died from endemic diseases. Those that survived adjusted to the multitude of circumstances in which they found themselves. They had to adapt and perhaps change many of their customs, values, and beliefs. And yet, among them remained the ancient ones, the teachers, the loved ones, the women, who maintained a seed of the original instruction, which was passed down from generation to generation. The Crossover Rituals became the entry points of knowledge and understanding of life and creation. They create a map for reawakening one’s personal and planetary position in the universe. And so, when Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh reports to me that her people are reindigenizing themselves, what she is referring to is that despite her people’s personal and generational experiences of trauma, “the fragmented pieces still contain our spirit.” The preceding comments on healing are certainly appropriate for pre-contact culture.

However, the processes of revitalization that the Bear Clan Mother employs are directed at a reinterpretation of the tradition for contemporary young women. In a socio-centric culture such as the Haudenosaunee, the importance of bridging the ego-centered Western constructions with the ideology of the nation in its best formulation is seen in the symbol of the Moon Lodge, and how that ancient symbol is understood today. The type of healing employed by Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh is not limited to an individual self, but is applicable to the context of cultural healing as well.

While it is difficult to generalize Native American beliefs and experiences because each community has its own unique identity, history, and response to the world, indigenous communities do have some shared memories that connect them to one another and to their ancestors. In a sense, one can still see their footprints on this earth: they laid out the path to guide others. It is the shared memory of why one walks the same path of life that they did, and this path is referred to as “original instruction.”

Original instruction entails a movement away from Western Cartesian thinking, which alienates people from the natural world, making the natural world an object that can be perceived and “managed” as separate from one’s immediate existence. This book attempts to bridge these separate worldviews, so that indigenous peoples and Western Europeans might reclaim who they are and to whom they belong, questions that are at the core of identity and belonging.

Over successive generations, First Nation people from around the globe have experienced the trauma of colonization and marginalization: “For hundreds of years, North America’s colonizers worked systematically to eradicate the indigenous cultural practices, religious beliefs, and autonomous political systems many among us now venerate.” Despite these efforts, indigenous peoples have survived. Sadly, while there exists extensive literature that documents these assaults, few record indigenous resilience or their desire to retrieve, reclaim, and nurture a still-living culture.

As indigenous communities around the world are gathering to both reclaim and share their ancestral wisdom, cultural contact, cultural change, and cultural adaptations are a given. Environments shift, new information arrives, foreign concepts and material goods travel continually across borders. No culture can remain static and survive over the centuries; rather, cultures devise strategies to understand new elements and connect their core values with the wisdom of their respective pasts.

Haudenosaunee and First Nation communities, who once spanned the territory from Lake Ontario to the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, are now diminished in size. Yet they are still large in the reach of their extended families residing on either side of the US-Canadian border. These connections of families and extended families transcend political and territorial barriers, for the Native Americans are connected not only to their immediate and extended family but “also to all the generations that have walked upon the land and to the unborn faces yet to come.” This is largely because the Haudenosaunee, who refer to themselves as “the people of the longhouse,” believe that they share kinship with all who reside on Turtle Island.

Many kinds of memories, specifically historical memories, are transmitted orally as well as through text, history, symbols, tradition, place, dreams, and narratives. What is significant for this work specifically is that the Haudenosaunee are highly oral in their tradition. The insights of Herbert Hirsch are useful in understanding this:

In attempting to reconstruct our own history from what Langer (1991) calls the “ruins of memory” we should be aware of the fact that what we come up with is composed partially of remembered experiences, partially of events that we have heard about that may be part of a family or group mythology, partially of images that we have recreated from a series of family remembered events … historians and philosophers agree that personal recollections are used to formulate both the individual and the collective past … it is an attempt to chronicle human events remembered by human beings. History is moved by a series of social forces, including economics, religion, and institutions, mainly political, technological, ideological, and military.

Just as historians create memory as they write history, this text documents a lived tradition and consequently creates an opportunity to explore another way of reconstructing memory.

Throughout this book, I will observe and document (as much as I have been given permission to) the call and original instructions transmitted by Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh. These instructions, Chief Jake Swamp tells us,

have become our shared memories about how humans are to conduct ourselves on this land we called North America. The instructions provide us frames of reference for looking at our relationship with the sacred universe, our first extended family. … We are connected to a great web of life.

Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh echoes and reaffirms this message through her own work as a Grandmother Moon ceremonialist. In her role as Bear Clan Mother and Lead Matron of the Moon Lodge Society, she underscores the need to reclaim their Crossover Ceremonies, because it is these rites that give indigenous youth a sense of purpose, dignity, and belonging. Connecting the people and celebrating the most important changes in their lives with them give the young adults this meaning. Crossover Ceremonies are young peoples’ entry into ancient knowledge and a timeless understanding of life. The life changes they pass through as well as their own personal stories are connected with and given meaning through the larger creation story.

[The] clan Mother’s duties have to do with the community affairs, the nation affairs, but they also have another role and that has to do with the spiritual side. … they must perpetuate the [traditional] ways but they must also set ceremonial times and be able to watch the moon for our people. We don’t have many people in this time who can communicate with the stars. … She must watch and always be ready to call the people together.

She is also quick to contend that her people have experienced not just individual trauma but intergenerational trauma that continues to affect their lives today, the core of their spirit. These traumas then, are things that cannot be minimized or compared with others. Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh states:

Any time the soul experiences trauma, whether in its mother’s womb, as a baby, a child, an adolescent teenager, a young adult, a middle-aged adult, an elder, pieces of our spirit a...