![]()

CHAPTER 1

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY

VILLAGE

FROM VANDERHEYDEN TO TROY

In 1707 Dirck Vanderheyden had purchased some 490 acres of land along the east bank of the Hudson River between the Poestenkill, the creek just north of present-day Canal Street, and the Piscawenkill, which emptied into the river between what are now Douw and Middleburgh Streets.1 When Lafayette visited in 1778, this acreage was mostly open farmland, dotted in places with scrub oaks and pines; the improvements consisted mainly of a handful of modest one-and-a-half-story, gambrel-roofed dwellings owned by the Vanderheyden family. For many years family members had refused appeals from emigrating New Englanders to subdivide their property, but in the 1780s the situation began to ease, as the Vanderheydens agreed to lease parts of the property. A New England merchant, Benjamin Thurber, was the first to secure a lot on River Street. He built a wood-framed store and in 1787 advertised that he sold European and West Indian goods and accepted furs and farm products in payment.2

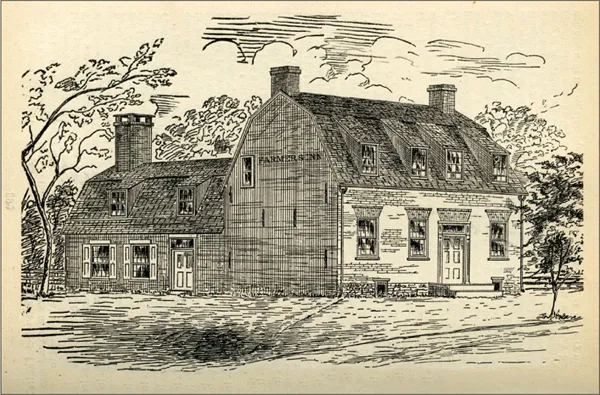

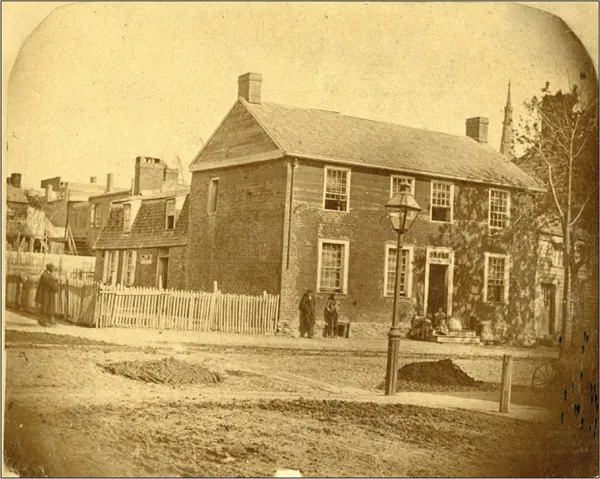

In 1786 Stephen Ashley, another New Englander, leased a former residence of Matthias Vanderheyden, located at the southeast corner of Division and River Streets, and converted it into a tavern (figures 1.1, 1.2). He also leased the right to run a nearby ferry across the Hudson, the only one in the vicinity. In 1790 Ashley moved his business a short distance to the north, just above the corner of today’s Ferry and River Streets, where he opened another tavern, entertaining farmers trading in Troy, lodging travelers en route to New York City, and offering “bounteous entertainment” on the Fourth of July. His ballroom, the largest gathering place in the village, was used for worship services in the years before churches were erected and for court sessions before the courthouse was built. One account stated that in May 1791 the tavern received two important vacationers—U.S. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, then a member of the Constitutional Congress, during their tour of upstate New York and New England.3

Fig. 1.1. Matthias Vanderheyden residence, southeast corner of River and Division Streets, 1792, later Stephen Ashley’s tavern, demolished

Fig. 1.2. Matthias Vanderheyden residence, southeast corner of River and Division Streets, after remodeling, demolished

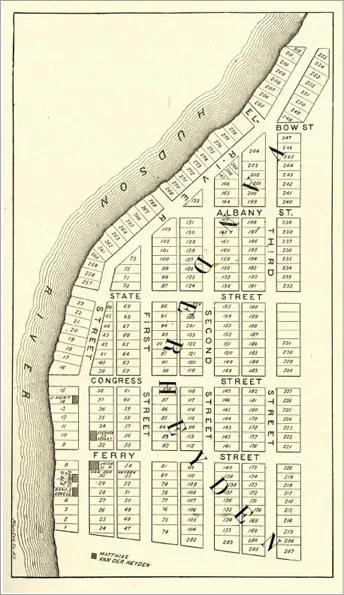

Meanwhile, in 1786 Jacob D. Vanderheyden, a great-grandson of Dirck, was persuaded to turn a portion of his land into a new town. He hired a Lansingburgh surveyor, Flores Bancker, to lay out a grid of streets and lots on the sixty-five acres that ran along the riverfront from present-day Division Street north to Grand Street and then east to what is now Church Street, the alley between Third and Fourth Streets. Bancker’s map, completed in May 1787, delineated 289 lots, most of which were 50 feet wide and 130 feet deep; the lots fronted on streets that were 60 feet wide; at the rear were 20-foot-wide alleys (figure 1.3). This grid was said to have been modeled on the century-old plan of Philadelphia but with the Troy streets being 10 feet wider. The extent of the surveyed area, which ran about 3,150 feet along the shoreline, suggested that the town had been laid out “with a view of its ultimately becoming a place of considerable magnitude.” Jacob Vanderheyden, who was well known locally as the “patroon,” gave the new town his family name, sometimes styled as “Vanderheyden’s.”4

Fig. 1.3. Map of Vanderheyden, based on original by Flores Bancker, 1787

The village got off to a strong start. The new settlers fully understood the advantages of being at the head of navigation on the Hudson: traders could easily load their cargo at the edge of the steep riverbanks, avoiding the rapids and the costly overland trek required to carry goods north to Lansingburgh, its upstream commercial rival. Three nearby swift-flowing creeks—the Piscawenkill, Poestenkill, and Wynantskill—had been powering mills for a century. A trader from Rhode Island wrote home in 1786 that “this country is the best for business I ever saw,” boasting that he had “done more business in one day than in one week in Providence.” When Elkanah Watson, a land speculator and canal promoter, visited Vanderheyden in 1788, just a year after the streets had been staked out, he observed that “several bold and enterprising adventurers have already settled here; a number of capacious warehouses and several dwellings are already erected.” Watson predicted, correctly, as it would turn out, that given its location on the Hudson and its proximity to Vermont and western Massachusetts, Vanderheyden would soon eclipse Lansingburgh.5

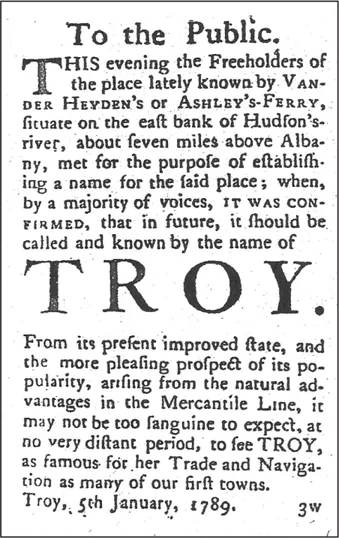

Vanderheyden was sometimes called Ashley’s Ferry, but the settlers from New England soon decided that the village needed a more progressive name, one that would downplay its Dutch origins and reflect instead their ambitious economic vision. On January 5, 1789, property owners “met for the purpose of selecting a name for said place” and immediately drafted a public notice announcing the result of their deliberations: the majority had agreed that “in future, it should be called and known by the name of TROY” (figure 1.4). A few days later a pundit wrote to the editor of the Federal Herald, the Lansingburgh newspaper that had published the notice about the new name, poking fun: “yesterday,” the letter read, “I hear’d that a neighbouring village had assumed the name of Troy—for what reason I cannot conceive; as I find not the least resemblance between the old city of that name, and this small village. … Some wag must surely have been playing a trick with the good people of the place, and is now laughing in his sleeve at their ignorance of ancient history.” Furthermore, the writer warned, the residents should be wary of how the four letters of the new name might be rearranged to spell Tyro, Ryot, or Tory.6

Fig. 1.4. Notice dated January 5, 1789, from the Albany Gazette, announcing the name change to Troy

In fact, the residents’ choice of a classical name proved prescient: Troy would be the first of the many towns and villages in New York State, and later in the Midwest, that would adopt a name from antiquity; indeed, the novelty of its classical name itself was said to have brought Troy “publicity and attracted attention.” Troy began to fulfill the settlers’ prediction put forth at their January 1789 meeting—that “from its present improved state, and the yet more pleasing prospect of its popularity, arising from the natural advantages in the mercantile line, it may not be too sanguine to expect at no very distant period to see Troy as famous for her trade and navigation as many of our first towns.”7

When the new name was selected in 1789, there were still only about a dozen dwellings, five stores, and fifty residents in Troy, but more New Englanders, along with settlers from Albany and Lansingburgh, soon arrived. A daily stagecoach between Lansingburgh and Albany began stopping at Stephen Ashley’s tavern in April 1789. An advertisement placed in an Albany newspaper just two months after the adoption of the new name announced that a house and store for sale were situated “in the flourishing Town of TROY.” Nearby sawmills, it was reported, were being “taxed to their capacity with orders for lumber and building material,” and building contractors “were in great demand.” Among them were Ebenezer Wilson and his younger brother Samuel, later famously known as “Uncle Sam,” who had walked over the Green Mountains from New Hampshire and were soon making bricks for foundations, walls, and chimneys from clay taken from the side of the hill near Ferry Street and Sixth Avenue (figure 1.5).8

Fig. 1.5. “Uncle Sam” Wilson residence, south side of Ferry Street near Seventh Avenue, demolished, drawing by Douglas G. Bucher

MEETINGHOUSE, COFFEE HOUSE, AND THE COUNTY COURTHOUSE

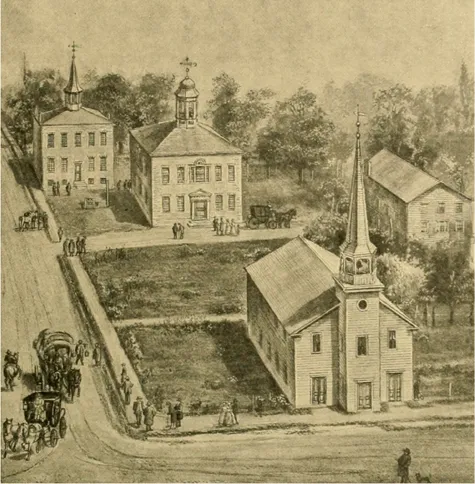

Built by the newly incorporated Presbyterian congregation, the first meetinghouse, like many of Troy’s first buildings, had a timber frame sheathed with clapboards (figure 1.6). Construction began in 1792 on land at the southeast corner of Congress and First Streets, on the middle of three lots donated by Jacob D. Vanderheyden. Located in what is now the west side of Sage Park, the church faced west onto First Street. It was fairly modest in size, just 40 by 60 feet in plan, and had a projecting bell tower and entrance, much like contemporary New England meetinghouses. Five contractors—Abel House, Robert Powers, Henry and John DeCamp, and Benjamin Smith—erected the framing, constructed the exterior walls, and shingled the gabled roof, but a shortage of funds delayed laying the floors until 1793. The rest of the interior was not completed until several years later. A “substantial pale fence” was authorized for the perimeter of the public square and the meetinghouse ten years later.9

Fig. 1.6. Bird’s-eye view looking east from First and Congress Streets, showing (clockwise from top left) the Rensselaer County Jail, first Rensselaer County Courthouse, Moulton’s coffee house, and Presbyterian meetinghouse in 1798, all demolished

In 1795 Howard Moulton, a distinguished Revolutionary War officer from Connecticut, erected a three-story frame building of similar size behind the meetinghouse, with its gable end facing Second Street. It was known as the Troy or Moulton’s coffee house; it had a ballroom and twenty-two sleeping rooms and also housed the Masons’ Apollo Lodge. A quarter century later the wood frame of the coffee house was incorporated into the new home of Emma Willard’s Troy Female Seminary.10

Meanwhile, early in 1792, the year after the new county of Rensselaer had been carved out from the vast territory of Albany County, Troy residents coalesced around a new economic opportunity: if it were selected as the seat of Rensselaer County government, Troy would naturally attract more settlers and more commerce. The new county would, of course, need a courthouse; a jail would also be required. To avoid showing any partiality to Troy or its rival Lansingburgh, and to save the county some money, state legislators from Rensselaer County decided that whichever village raised the most money for the new courthouse would win the designation of county seat. To the astonishment of Lansingburgh residents, Troy promoters subscribed considerably more than their competitors had raised. The state legislature declared Troy the winner. The legislators appointed five commissioners to oversee construction, contract with builders, and purchase building materials.11

In March 1793 Jacob D. Vanderheyden, one of the five commissioners, donated three building lots at the southeast corner of Second and Congress Streets as the site for the new courthouse and jail. Construction of the courthouse began immediately. A later drawing shows it as a two-story brick structure, with a hipped roof and a cupola, where a bell made in New York City was hung. The main entrance, facing Second Street, was flanked by two columns supporting a pediment; an elegant Palladian-style window illuminated the second floor. The Court of General Sessions of the Peace met in the courthouse for the first time in November 1794. The jail was a separate brick building located behind the courthouse, its windowless north wall abutting Congress Street and its entranceway facing a fenced yard with a whipping post and stocks. The windows above the entrance were secured with iron bars, and a spir...