![]()

1

Presented to David Marshall

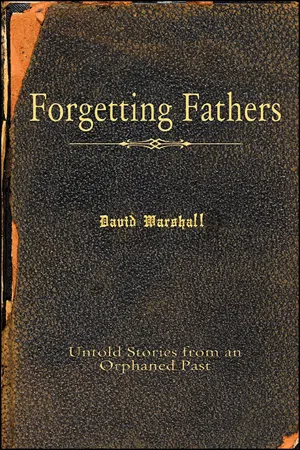

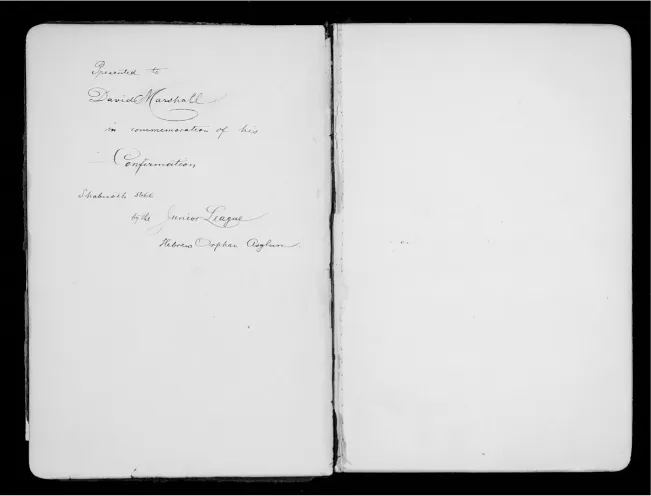

For me, the story begins with a name embossed in gold, Gothic letters on the black cover of a book, inscribed in neat handwriting on the first leaf. The Bible is presented to “David Marshall.” It is Wednesday, May 30, 1906, the day he is confirmed. He is, according to the records of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum of the City of New York, fourteen years old. There is an inscription on the first page: “Presented to David Marshall in commemoration of his Confirmation Shabuoth 5666 by the Junior League Hebrew Orphan Asylum.” The penmanship is fancy and formal, the capital letters demurely calligraphic; yet the M in Marshall loops down with a dramatic flourish to underline the last name. Shabuoth, commemorating the delivery of the tablets with the Ten Commandments to Moses on Mt. Sinai, is in “modern times,” according to a contemporary religious instructional manual, “Confirmation Day,” the “day of consecration of Israel’s youth to the faith of their fathers.” For many Reform Jews at the turn of the century, the confirmation ceremony replaced the bar mitzvah.1

As he stands there, recognized as a man in the Jewish tradition, receiving the new Bible inscribed with his name, he is fatherless, an orphan. His father died on February 14, 1901, and he has been an “inmate” of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum since March 9, 1903. Some months after his arrival, the new superintendent of the asylum, Rudolf I. Coffee, “abolished the practice of having the children identified by a number and ordered that they be addressed by their first name.”2 His number is 2633. “David Marshall” is not his name.

For me, the story, at least the story about the name, begins with my name. I was born “David Marshall,” yet as a child I learned that we came to be called “Marshall,” we came to call ourselves and write our name “Marshall,” following the Americanization of names so common among late-nineteenth-century Jewish immigrants and their children. I was born in 1953 in New York City, almost two years after my grandfather, David Marshall, died; thus, since the faith of my fathers calls for a child to be named after a parent or grandparent who recently died, I was named David Marshall in memory of my grandfather. According to the family story, it was David Marshall, born more than sixty years before me in New York City, who changed the family name, not only for himself but also for his mother and siblings—and for those of us who followed. (There is no evidence of a legal name change.)

Bible inscribed to David Marshall, Hebrew Orphan Asylum, 1906.

Bible inscribed to David Marshall, Hebrew Orphan Asylum, 1906.

If this were merely a story about Americanization and assimilation, the replacement of an Eastern European Jewish name with an Anglo-Saxon substitute or abbreviation, there would be no story. What was stranger and more complicated is that no one seemed to know the original name, or the origin of the name. My father and grandmother both said (they insisted) that they did not know the original name. It was not forgotten; it was never known, never spoken. My grandfather’s mother, whose first name was Lena, lived until the age of ninety. We called her Grandma Marshall. I was only seven when she died in 1960, and I was too young to ask her about her “real name” or the name of the man she had married seventy years—a lifetime—earlier. I was too young to know that Grandma Marshall had a story. All my father knew about the name was that his grandfather’s first name had been Aaron, but he went by the name Harris after he immigrated to New York.

We imagined that the name had been Marshak. In college, I read Russian novels translated by David Margashack and the name resonated. There was speculation about Eastern European names that ended with “-sky.” Some relatives believed (rather implausibly, in my opinion) that the last name originally was Harris. I often wondered if my father really knew the name, since he contradicted any theories advanced by our relatives. Either he knew the correct name, I supposed, or he didn’t think that anyone could know. I asked him to disclose the secret on his deathbed. There were two weeks in which he knew that he was about to die. Lucid, calm, philosophical, yet sometimes released from inhibitions, he seemed to be mentally reviewing the stories he wanted to know the endings of, the socially unacceptable questions he had always wondered about: whether this person had had an abortion, whether that person had had an affair.

At one point I reminded him that it was the time for his deathbed confessions, not those of others. This is your last chance, I pleaded, to tell us what the name had been before it was changed to Marshall. He insisted that he really did not know his father’s and grandfather’s original name, that he had never known it. He had never asked. My father said that his father did not like to talk about the orphanage, that he seemed bitter about those years. He reported that his mother “always said he was resentful of the fact that he grew up that way.”3 What was it in my father’s father’s stories (or lack of stories) that proscribed his family’s curiosity about his childhood and his name—their name? Was the family name forgotten merely because it was unimportant, a last vestige of an immigrant world left behind by a generation born in New York, discarded in favor of a less ethnic, less foreign, less Jewish name?

If David Marshall’s history seemed to stop (or start) at the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, we had stories, or at least the outlines of stories, about the families of my other grandparents. My grandmother Jeanette, my father’s mother, who married David Marshall in 1922, was born in New York City to Russian and Polish immigrant parents, Louis and Anna Levitt. She talked about her family and was close to her brothers and sisters. We knew that her father had manufactured children’s shoes. (About ten years ago a distant cousin in Israel sent my father a family tree that included my grandmother’s mother, listed as Elka Channa Wolarsky, traced back to one Wolf Wolarsky, born in Poland around 1780. It lists my father’s parents, Jeanette Levitt and David Marshall, as Janet Levitt and Richard Marshall. Although my grandmother’s mother was married under the name Hannah Volarsky, on my grandparents’ marriage certificate she is listed as Anna Waller.) My grandmother was raised in Brooklyn. I remember her imitating the Yiddish accents of some of the residents of her North Miami Beach condominium complex, and into her nineties she answered the phone with an upper-class “Hel-lo …”—the second syllable elongated and almost British—that she must have learned from Hollywood movies. My mother’s parents, Moe and May Horowitz, came to New York from Poland in the 1920s. Relatives in New York changed their names from Marcus and Manya to Moe and May. (When I was young, I was embarrassed that my grandfather shared a name with one of the Three Stooges; I didn’t even know that Moe Howard’s name was actually Moe Horowitz.) We heard the story about how Grandpa Moe’s father had come to America to make money to bring over his family from Poland but was cheated out of all his savings by his boss. He returned to Poland “a broken man” and died soon after, leaving my grandfather as the “man of the house” at a young age. We were told that my Grandma May’s family had both prominent rabbis and socialist leaders. As I learned, these included Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Rothenberg Alter, the founder of a Hasidic dynasty and the first Gerer Rebbe, born in Poland in 1799 and a descendent of the thirteenth-century Rabbi Meir Ben Baruch of Rothenberg; and Victor Alter, a well-known Bundist activist in Poland and a member of the Central Committee of the Second International, who was executed by Stalin. Growing up, I knew that when my mother had left college to become an actress, she had taken the name Helene Alter as her stage name because Helene Horowitz sounded “too Jewish.” When I was in college, and I had to use a pseudonym when submitting some poems for a creative writing prize competition, I used the name “Moses Alter”— re-inscribing Alter in the lineage of a Jewish patriarch whose mother gave him up for adoption to a non-Jewish family.

Just as they had stories, my mother’s parents had family photographs from the old country: cabinet-card tableaux of brothers and sisters in formal poses and fine clothes, staged domestic scenes, my grandfather in uniform. Most of their relatives, those who had not emigrated, died in the Holocaust. Growing up, I saw photographs of various great-grandparents, but I never saw a photograph of my father’s paternal grandparents, or their relatives from the Old World. I knew of (but do not remember meeting) my grandfather’s siblings but did not know of siblings, cousins, or other relatives from my paternal great-grandparents’ families. Yet my father’s parents and paternal grandparents were not Holocaust survivors who kept their silence about a world that had exiled them, murdered their families, and obliterated their genealogy. Was the family name forgotten, erased, or repressed? Had it disappeared because it was important rather than unimportant?

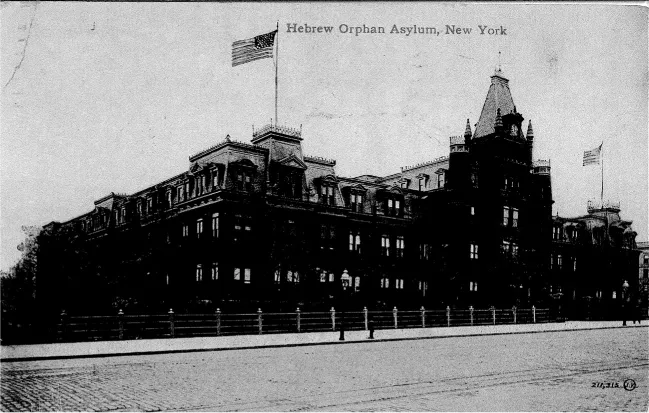

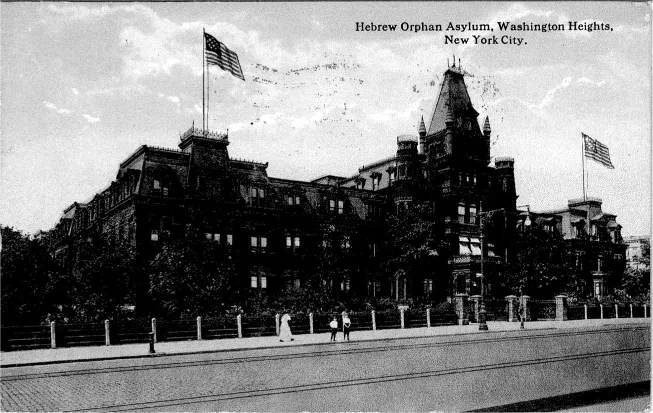

American Jews were wary of anti-Semitism and Jewish quotas; they were insistent that they were American, especially those born in New York in large immigrant communities around the turn of the century. At the fiftieth anniversary of the first building of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum (HOA) on April 10, 1910, twelve hundred orphans marched onto the stage of the New York Hippodrome before five thousand spectators (including New York City Mayor William J. Gaynor) and sang “America” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” David had been discharged from the orphanage by this time, but his brothers Rubin and Isadore were still inmates so they must have been on this stage. The boys wore military-style suits; the cadet corps of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum performed a patriotic number called “Rally ’Round the Flag” and fired real rifles with blanks.4 Color postcards of the orphanage from this decade display two American flags flying prominently from the turrets of the building.

Postcard, Hebrew Orphan Asylum.

Postcard, Hebrew Orphan Asylum.

Upon entering the main hall of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum in the first years of the twentieth century, one would have encountered a twelve-foot-high bronze sculpture representing a wishful allegory of America and the Old World: “the ruins of three dynasties—Assyria, Egypt, and ancient Rome—and upon this base a red marble column of fasces stands, emblematic of the United States.” According to a description published in the New York Times, “The serpent of intolerance winds its way through these ruins and tries to coil itself around the column of the Union, but is being destroyed by the American eagle.”

Sculpted by Moses Ezekiel, a Jewish, Confederate army veteran whose bust of Thomas Jefferson is in the United States Capitol, the sculpture was designed as a memorial to Jesse Seligman, a prominent banker and former president of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. Beside the column that held Seligman’s bust, “an orphan girl stands holding a scroll upon which is inscribed, ‘His Character Knew No Race or Creed.’ ”5 Although the sculpture stands in what was called the Memorial Hall, the orphan, like the United States, stands on the ruins of the past, as if freed from historical memory.

The Hebrew Orphan Asylum of the City of New York, founded in 1860, was a nationally respected institution that rescued thousands of orphaned children from loss and poverty, educating and training them for productive lives. It was located between 136th and 138th streets on Amsterdam Avenue, across the street from where the campus of the City University of New York was built between 1903 and 1907. The imposing Second Empire Renaissance–style building was designed by William H. Hume, a prominent architect of commercial and institutional buildings. A former inmate who had arrived as a child in 1929 recalled: “Its Victorian Gothic crenellated architecture—crowned with a tall clock tower—made newly arriving children think of fairytale castles.”6

About 75 percent of the children, like my grandfather and his two brothers, had a living parent who could not afford to care for them. There is a photograph of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum published in King’s Views of New York in 1903, the year my grandfather and his brothers arrived at the orphanage, with the caption: “Maintains large asylum, very finely equipped, where 1,000 orphans and indigent boys and girls are sheltered and educated. Hebrews rarely neglect their poor and unprotected.”7 The orphanage had many wealthy and influential trustees and patrons, many from the German-Jewish aristocracy of New York, such as department store magnates Isador Strauss and Louis Stern, and the stockbroker Emmanuel Lehman. An April 29, 1912, article in the New York Times described a meeting of the HOA trustees at which the political leader and lawyer Edward Lauterbach and the banker Jacob Schiff broke down in “sobs” as they paid tribute to their fellow trustees Isador Stern and Benjamin Guggenheim, who two weeks earlier had perished on the Titanic. There were thousands of loyal alumni.8

Memorial Hall, Hebrew Orphan Asylum, Eighty-Third Report of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum of the City of New York, 1906. Courtesy of the Collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.

In the months after David and his younger brothers Rubin and Isadore arrived in March of 1903, Superintendent Coffee began his appointment by introducing a period of liberalization and “de-institutionalization.” In 1904, addressing a system of discipline reminiscent of English boarding schools, Coffee announced “the absol...