![]()

1

Slapstick Spectators

Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914)

THE FORM AND MANNER OF COMEDY that we now call slapstick originated in popular stage entertainments, stretching as far back as the Italian commedia dell’arte but more immediately in pantomime, minstrelsy, burlesque, medicine shows, English music hall, circus, and vaudeville. Indeed, when one considers slapstick historically, one is struck by the fact that what are now remembered as the great silent comedies of the 1920s are belated and deracinated instances of a form of comedy that thrived more fully in certain corners of the nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century stage, places where the gag did not have to continually reconcile itself to the demands of narrative. The fact that the feature-length silent comedies that are well remembered today are not the full flowering of a preceding stage tradition but rather a kind of erasure of the stylistic and even ideological diversity of multiple stage traditions is apparent in the relative absence of female performers and actors of color. The great Marie Dressler, considered below, became a film star in her own right, but only by shifting the generic tense of her work, as in her great success in the comic melodrama Min and Bill (1930). And we might not remember Bert Williams as a slapstick clown, but his work in pantomime and, more generally, in the peculiar form of black minstrelsy was understood by his contemporaries to be the very pinnacle of stage comedy.

In each of these theatrical contexts, and again in the cinema itself, slapstick was both style and form—a manner of performance, derived from pantomime and from the need for “business” on the comic stage, and the various forms that have housed this manner, from the minstrel and burlesque olio to the variety act structure of the vaudeville show. In these cases, slapstick performance was not subordinated to narrative form, as it would be in the studio-era Hollywood film, but functioned instead within a larger economy of spectacle and affect. The structure of the vaudeville bill, for instance, took into account the unstable nature of audience attention as it organized itself around the production of affect: opening and closing acts typically did not rely upon dialogue so that they could accommodate the filling and emptying of the theater; the fifth and eighth acts—the act before intermission and the penultimate act, respectively—were showstoppers toward which the rest of the program built. In cases where slapstick performance occurred within the constraints of narrative, it did so in contexts that were formally and ideologically distinct from that of the “legitimate” stage, as in the afterpiece of the minstrel show or in the travesty portion of the burlesque program. Although the vaudeville act allowed for the direct acknowledgment of the audience (and hence an acknowledgment of that form), burlesque was almost entirely self-referential, taking part in a wide-ranging travesty of not simply the legitimate theater but also middle-class social mores. All of which is to say that the self-reference that is present in the slapstick film comedy has origins that should be understood through these earlier stage traditions.

The Keystone Film Company’s Tillie’s Punctured Romance was produced on the very cusp of the studio era, making it much closer to these stage forms than the other films considered below. It was, for this reason, concerned with questions about the nature of film spectatorship as well as the form and status of what would become the industry’s core product, the feature-length narrative film. As Keystone’s first feature-length film, Tillie’s Punctured Romance was a vehicle for the comedian Marie Dressler, who was then famous on the Broadway stage. The film co-starred Mabel Normand and a young (and not yet world famous) Charles Chaplin. The film is of particular interest for the study of slapstick comedy, and indeed for the generic differentiation of the studio-era cinema more generally, because it represented the first attempt to situate the distinct formal and stylistic features of the physical comedy within the narrative constraints demanded of the feature film. It is in this sense a bridge between earlier stage comedy and the more well-remembered features of Keaton, Chaplin, Lloyd, and Langdon. Contemporary reviews of the film as well as Keystone’s promotional materials were highly conscious of this fact. Keystone’s one-page advertisements, for instance, claimed that the film represented “THE IMPOSSIBLE ATTAINED,” the phrase staking the claim that Mack Sennett was the first producer to successfully—and improbably—cram a whiz-bang mode of comedy into the pendulous form of the feature film.

Prior to founding the Keystone Film Company, Sennett himself worked at Biograph, first as an actor and later as director of the company’s comedy unit. At Biograph, he undertook a kind of apprenticeship under D. W. Griffith, whom he later referred to as “my day school, my adult education program, my university.” At Biograph, Sennett worked on many of the short subjects that he would later travesty in his own studio, from The Lonely Villa (1909), which became Help! Help! (1912), to The Fatal Hour (1908), which became At Twelve O’Clock (1913), to the films below, Griffith’s A Drunkard’s Reformation (1909) and the six-reel Tillie’s Punctured Romance. Sennett’s “burlesques on melodrama” at Keystone (the phrase was used by the studio in its promotional materials), and their signature style, were tremendously successful. They formed a major part of Keystone’s output and helped to define the studio’s style and to articulate its distinct appeal to a largely working-class audience. Their movement is from a Griffithian melodrama that drew heavily from the popular stage to broad comic travesty, which in turn drew from stage traditions of vaudeville, minstrelsy, and burlesque.

Sennett’s travesties of specific Biograph shorts are of further historical and theoretical interest because of the influence that Griffith’s films exerted upon the formation of Hollywood film style and form. Asking how and to what effect the travesty of A Drunkard’s Reformation that is interpolated in Tillie’s Punctured Romance transformed its source, and how it is placed within the structure of the larger, six-reel feature, actually reveals something about this broader history of style and form. A better account of the nature of this movement between source film and travesty, and of the reception of both films, provides a way to better understand the Hollywood feature-length film in general as well as help to articulate what I will call the “gesture of display” that characterizes this travesty and which provides some purchase for thinking more deeply about the mode of slapstick comedy.

Griffith’s ten-minute film contains thirty-three shots: the opening seven establish the relations between a family of three, the husband and father of which is the titular drunkard. The following twenty-four shots—which take up about two-thirds of the running time of the film—consist of the father and his daughter at a stage adaptation of Emile Zola’s L’Assommoir during which he is convinced, by virtue of his viewing of the play, to abstain from drink. The final two shots see the father and daughter return home to the mother, the father’s request for forgiveness, and a concluding tableau of the happy family gathered before a glowing hearth.

Griffith structures the middle, play-within-a-film sequence entirely by means of an alternation between the drama onstage and a medium long shot of the father and daughter in the audience. The drama here is not that of the stage performance, but rather that of the father’s reformation, which unfolds in concert with the action of the play. After an initial establishing shot of the theater, this alternation is uninterrupted between shots nine and thirty-one (except by title cards). As Tom Gunning has argued, the sequence takes a proto-shot-reverse-shot form: the film figures each action frontally and in staging that marks the father as part of a larger audience, but makes clear, both by means of a rope that separates the spectators from the stage and by its foregrounding of the father and daughter and the bright whites of their costumes, that we are to read the play’s action through, or alongside, these spectators, and through the father specifically. (It is internal to the message of Griffith’s film that the father is not filmed in relative isolation, as he would have been as the continuity system became more codified just a few years later, but is instead shown to be part of a larger audience.)

A Drunkard’s Reformation is a privileged moment for the embourgoisement of the cinema. The film is foundational to Gunning’s account of Griffith’s creation of the “narrator system” and the particular stylistic and ideological constellation of a mode of filmmaking that would eventually be understood as classical. The film was one of the very first films approved by the National Board of Censorship, which had been created in the wake of New York City’s shuttering of the nickelodeons in 1908. The censorship board was embraced by the Motion Picture Patents Company as a means for ensuring the political stability of film exhibition and for advancing its appeal to middle-class patrons.

In Gunning’s influential argument, A Drunkard’s Reformation does not simply function as a moralizing tale about the evils of drink but actually advocates for the value of motion pictures as themselves reformist. He argues that Griffith uses this alternation to depict a psychological change in an individual character and, consequently, to carry the ideological claim that the cinema might be used in the service of this reform, rather than simply in service of suspense. That is, A Drunkard’s Reformation advances, in almost self-conscious fashion, a particular idea about the form, style, and even audience of the cinema. As would become clear in Griffith’s later features, the cinema is equated here with the narrative and affect of melodrama, which is in turn underwritten stylistically by what would become the continuity system.

This implies a fascinating question: What becomes of this sequence and its particular ideological charge as it is transformed by Sennett into the target of travesty? There is little in the historical record to suggest the origins of the story of Tillie’s Punctured Romance, which was supposed to be a loose adaptation of Dressler’s successful stage comedy Tillie’s Nightmare. Several historians have suggested that the plot of Tillie’s Punctured Romance (and there isn’t much of it) bears some resemblance to the story that was told in the hit song from Dressler’s play, “Heaven Will Protect the Working Girl.” In broad strokes, the story of Sennett’s film is this: Tillie, a girl from the country, is persuaded by Chaplin’s tramp (here, “The Stranger”) to elope to the big city. Upon their arrival, The Stranger and his female accomplice (Mabel Normand, “The Other Woman”) steal all of Tillie’s money. Tillie is left to fend for herself until her wealthy uncle apparently dies in a mountain climbing accident, at which time she inherits his fortune. Reading about this, The Stranger finds his way back into her graces in order to marry her and make off with the inheritance. It is eventually discovered, however, that the uncle did not die. Upon his return, the uncle sends Tillie and The Stranger out of his home, but not before Tillie discovers Chaplin lavishing his attentions on The Other Woman. In the end, neither Tillie nor The Stranger nor The Other Woman is left with anything, with the exception of a potential friendship between Dressler and Normand, who are united in their rejection of Chaplin’s advances.

The film’s comedy is so broad, however, that to describe the film’s story in this way is, in an important sense, to misrepresent it. The humor and indeed the appeal of Tillie’s Punctured Romance derives from its exuberant, partially improvised performances and from the film’s almost antinomian relationship to other stage and film texts. The voluminous Dressler, for instance, plays a “country girl” who is a burlesque version of the petite and virginal figure familiar from the contemporary stage (and who would soon find her onscreen articulation in the waif-like figure of Lillian Gish). And Chaplin’s Stranger is familiar as the villain of the melodramatic stage, but whose lack of graces (and of adequate clothing) figure him not with the false suavity of this villain but as an almost lumpen and fundamentally unserious con artist.

Much of the film’s eighty-five minutes consists of calculated digressions from this basic plot. These digressions are used for multiple comic purposes and bear different relationships to the story. For instance, several minutes are set aside for Dressler’s famous drunk dancing routine (a staple of stage performances of Tillie’s Nightmare), which is of some importance for setting up her relationship to the wealthy uncle. (His character reference appears to release her from the jailing that was the result of her dancing.) Alternately, the opening reel in which Dressler’s and Chaplin’s characters are introduced to each other contains several minutes of violent slapstick that bears only a tenuous relation to the development of their relationship.

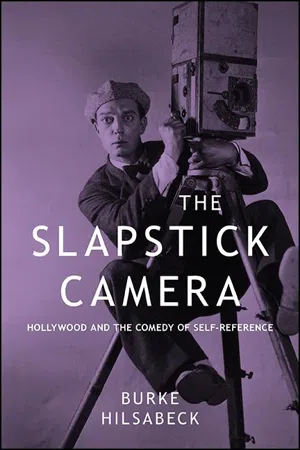

Sennett interpolates his travesty of Griffith into the third reel, where it is sandwiched between Tillie’s release from jail and her taking a job as a waitress. The story of Tillie’s Punctured Romance relies throughout on its viewers’ familiarity with the plots of melodramas, such that the sequence at first appears to set the stage for a change in fortune in which Chaplin and Normand are set upon by the police and are perhaps driven to repent. Indeed, after a title card that calls to mind Griffith and Biograph (“A MOVING PICTURE STRANGELY SHOWS THEM THEIR OWN GUILT AND ITS POSSIBLE CONSEQUENCES”), they take their seats in the cinema next to a man who turns out to be a cop. What follows is a five-minute sequence in which Chaplin and Normand watch this film-within-the-film (a crime melodrama called “A Thief’s Fate” that is mysteriously identified by its title card as a Keystone “farce comedy”), signal to each other their own resemblance to the characters onscreen, disrupt other patrons in the theater, and leave (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. “A Thief’s Fate” (Tillie’s Punctured Romance).

In an important sense, the joke lies in the fact that Sennett’s travesty bears no narrative relationship to the rest of the film. The film-within-the-film is supposed, like Griffith’s stage play, to cause The Stranger and The Other Woman to reflect upon their own misdeeds, which are mirrored exactly in the story of “A Thief’s Fate.” But it is less that they are not persuaded by the similarity between their actions and the story onscreen and more that they seem unable to form the moral judgment that formed the heart of Griffith’s drama, despite the fact that their comic business in the audience shows them to grasp the similarities between themselves and the characters onscreen. (Normand compares the villain’s moustache to Chaplin’s and even goes as far as to mouth “That’s you” in reference to him; in a further moment of meta-diegetic complexity, the villain’s female accomplice is referred to, in a title card, as “the other woman.”) As Rob King has written, “What they have learned from the film is the imminent possibility of being caught, not the moral consequences of their wrongdoing—and, as their continued misdeeds will prove, this hardly counts as ‘reformation.’ ” What is more, they are not caught: they simply watch the movie and leave.

In both style and form, this sequence in Tillie’s Punctured Romance displays a greater complexity of form and technological accomplishment than A Drunkard’s Reformation. While Griffith’s film is built of a simple alternation between the action onstage and the father and daughter in the audience that is...