![]()

PART I

THE POPULAR TRADITION

All too often a textbook picture of Theravada Buddhism bears little resemblance to the actual practice of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. The lived traditions of Myanmar,1 Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka seem to distort and sometimes subvert the cardinal teachings of nibbana, the Four Noble Truths, or the Noble Eightfold Path familiar to the Western student of Buddhism.2 The observer enters a Theravada Buddhist culture to discover that ordination into the monastic order (sangha) may be motivated more by cultural convention or a young man's sense of social obligation to his parents rather than the pursuit of transforming wisdom; that the peace and quiet sought by a meditating monk may be overwhelmed by the amplified rock music of a temple festival; that somewhat unkempt village temples outnumber tidy, well-organized monasteries; and that the Buddha, austerely imaged in the posture of meditation (samadhi) or dispelling Mara's powerful army (maravijaya) is venerated more in the hope of gaining privilege and prestige, material gain, and protection on journeys than in the hope of nibbana.

The apparent contradiction between the highest ideals and goals of Theravada Buddhism and the actual lived tradition in Southeast Asia has long perplexed Western scholars. In his study of Indian religions, Max Weber made a sharp distinction between what he characterized as the “otherworldly mystical” aim of early Indian Buddhism and the world-affirming, practical goals of popular, institutional Buddhism that flourished in the third century C.E. under King Asoka and later Buddhist monarchs.3 Even recent scholars of Theravada Buddhism have been influenced by Weber's distinction in their studies of Buddhism as a cultural institution and an ethical system.4

To be sure, the Theravada Buddhism of Southeast Asia, not unlike other great historic religions, defines ideal goals of moral perfection and ultimate self-transformation and the means to attain them, but at the same time, Southeast Asian Buddhism also provides the means by which people cope with day-to-day problems of life as well as a rationale to justify worldly pursuits. Both goals are sanctioned in the writings of the Pali canon, the scriptures of Theravada Buddhism.5 The way to the transcendence of suffering called the Noble Eightfold Path presented in the first public teaching attributed to the Buddha in the discourse known as “Turning the Wheel of the Law” (Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta), includes advice appropriate to monks, such as meditation, but also the laity, such as right ethical action. The goals of Buddhism are, in short, both nibbanic and proximate—a better rebirth, an improved social and economic status in this life, and so on; the two are necessarily intertwined. We find in the Pali canon justification for both spiritual poverty and material wealth. Even as the monk or almsperson (bhikkhu/bhikkhuni) is enjoined to eschew worldly goods and gain, it is wealth that promotes both individual and social well-being when generously distributed by laypeople unattached to their possessions.6

Any broad, holistic analysis of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia should take into account not only its highest ideals and varied practices, but also its seeming contradictions. For example, rituals designed specifically for the benefit of the soul of the deceased seem to undermine the central Theravada doctrine of anatta or not-self/not-soul. The student of Theravada Buddhism should keep in mind, however, that the not-self doctrine can be interpreted as sanctioning such monastic pursuits as meditation, whereas the doctrines of kamma (Sanskrit, karma) rebirth (samsara), and merit (puñña) justify a wide range of other moral and ritual acts.7 These are distinctive but related domains within the broader context of the Theravada tradition; they should not be seen as contradictory. In the Pali texts, both ultimate and proximate ideals are promoted. The tradition affirms that the Buddhist path is many forked and, furthermore, that people are at different stages along the path. Explanations that seek somewhat arbitrarily and rigidly to differentiate teaching and practice, the ideal and the actual, run the risk of sacrificing the interwoven threads of religion as they are culturally embodied to the logic of consistency.

With this admonition in mind, I use the term, “popular tradition,” with some hesitancy; no value judgment is intended. “Popular” in this context does not mean less serious, less worthy, or further removed from the ideal; rather, it refers to Theravada Buddhism as it is commonly perceived, understood, and practiced by the average, traditional Sri Lankan, Burmese, Thai, Cambodian, and Laotian. What defines their sense of religious and cultural identity, the contexts in which this identity is most readily investigated, are rites of passage, festival celebrations, ritual occasions, and behavior as exemplified in traditional stories. One goes to the temple or the temple-monastery (wat) to observe many of these activities, hear the teachings as handed down orally from monk to layperson, and view stories depicted in religious art and reenacted in ritual. Institutionally, the religious life of the Theravada Buddhist focuses on the place of public worship, celebration, and discourse. Symbolically, the temple-monastery is not only the “monk's place” or sangha-vasa for the study of the dhamma, but also the “Buddha's place” or buddha-vasa where the Buddha is made present and venerated in images and enshrined relics.

In the following section I shall explore popular Buddhism in Southeast Asia with a focus on Thailand, in these contexts: rites of passage, festival celebrations, and ritual occasions, beginning with ideal behavior or life models personified in traditional myths and legends. The two underlying themes will be: the syncretic nature of popular Buddhism as part of a total religious-cultural system; and the role of religion in enhancing life's meaning through the integration and interpretation of personal, social, and cosmic dimensions of life.

IDEAL ACTION

Doctrinally, ideal action in Theravada Buddhism can be described as meritorious action (puñña-kamma) or action that does not accrue demerit (papa-kamma). At the highest stage of spiritual self-realization, the state of arahantship, one's actions are totally beyond the power of kamma and rebirth (samsara). Terms used to characterize ideal behavior and attitudes are truthfulness (sacca), generosity (dana), loving-kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), equanimity (upekkha), wisdom (pañña), and morality (sila), to name a few. In both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism these virtues are referred to as “perfections” (parami or paramita) of character associated with the person of the bodhisatta (Sanskrit, bodhisattva), one who is on the path to Buddhahood. These perfections are depicted in various ways appropriate to audience and context. They are exemplified in the narratives of moral exemplars, such as Vessantara and Sama who appear in the last ten of the 547 Pali jataka tales, other late canonical texts such as the Cariyāpi₪aka, the fifth century commentaries of Buddhaghosa and Dhammapala, vernacular narratives, and most important, in the life of the Buddha.8 Such stories are well known and are one of the principal means through which ideal life models are taught.

Historically, the Buddha is understood as the founder of the tradition (sasana) that is called Buddhism. Beyond that, however, his life story becomes paradigmatic for every devout follower who seeks the same goal of enlightenment/awakening he achieved, especially the Buddhist monk. Before Prince Siddhattha becomes the Buddha, he seeks to discover a deeper meaning to life beyond the inevitable limitations of old age, suffering, and death. He embarks on a quest for a personal knowledge that transcends the inherited traditions of his highborn social class. Departing from the life of a royal householder, he becomes a mendicant, seeking out learned teachers, engaging in the ascetical regimens of the renunciant, and training the mind in contemplative exercises (samadhi). Eventually, Siddhattha discovers a higher truth not limited to the conventional, dualistic perceptions of self and other, or the philosophical constructions of eternalism and nihilism. His profound insight into the non-eternal and non-substantive (anicca), causally interdependent and co-coming-into-being (idappaccayata) nature of things enabled the future Buddha to overcome the anxiety (dukkha) rooted in the awareness of human finitude and of the conditional nature of life. In an ideal sense every follower of the Buddha seeks the truth he achieved at his awakening (nibbana). Nibbana is not an abstraction or a mystical, alternative reality but a mode of being-in-the-world. It signifies that way of life as an achievable reality. Although one cannot always ascertain the precise intentions that lead a young man to ordain in the Buddhist monastic order, symbolically his ordination reenacts the Buddha's story.

The central teachings of Theravada Buddhism emerge from the narrative of the Buddha's life. Broadly speaking, the sutta literature in the form of the Buddha's dialogues represents episodes linked together as segments of the Buddha's life, like pearls strung on a single strand. Each pearl can be admired in and of itself but only when the pearls are strung together on a thread do they become a necklace. Similarly, each sutta episode conveys particular teachings, but these teachings are embedded in the narrative framework of the Buddha's life. The Buddha's teaching or dhamma is inseparable from the person and life story of the bodhisatta who sought to see through the apparent contradictions and sufferings of life to a deeper truth and, having succeeded, taught this truth by word, deed, and the power of example.

When Sri Lankan, Burmese, Thai, Laotian, or Cambodian Buddhists enter a temple or approach a reliquary (cetiya, Thai, chedi), they are in a sense encountering the Buddha.9 The reliquary enshrines Buddha relics, regarded as artifacts of his physical being or reminders of his life. Buddha images in varying postures remind the viewer of the Buddha's struggle with the tempter Mara, the Buddha's enlightenment and his teaching; murals visualize in a narrative form long-remembered, embellished episodes from his life. The most commonly seen murals are depictions of his miraculous birth; the four sights or scenes in which he encounters old age, suffering, death, and a wandering truth seeker that prompt him to renounce his princely life; his enlightenment experience under the Bodhi tree; and his first teaching delivered to five ascetics.

Bronze images and murals of the life of the Buddha tell a story that is not merely an inspired tale of the past, but also an ever-present reality. The Buddha represents the possibility of overcoming the blinding ignorance caused by sensory attachments and the attainment of the twin ideals of equanimity and compassion, and personifies the way whereby others may discover this truth for themselves, or by relying on the power of the Awakened One can at least improve their lot in this life or in future lives.

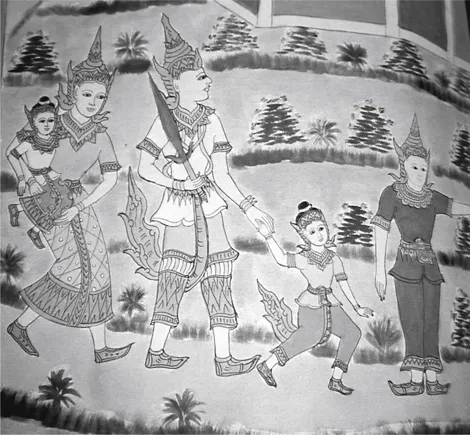

The Buddha's story, however, is not the sole ideal life model.10 In the Theravada tradition the lives of heroes and saints, particularly in the form of jataka tales that tell of the previous lives of the Buddha, embody highly regarded ethical virtues and spiritual perfections. In these stories the reader encounters narrative paradigms rather than scholastic discussions of Buddhist doctrinal ideals. The most celebrated jataka is the story of Prince Vessantara, the last life of the Buddha prior to his rebirth as Siddhattha Gotama, who exemplifies the perfection of generosity (dana).11

As the story begins, Vessantara, prince of Sivi, offers his kingdom's white elephant with magical rain-making powers to the neighboring territory of Kalinga to end their drought. The citizens of Sivi, incensed by this generous act that could jeopardize their own well-being, banish Vessantara and his family to the jungle. Before his departure he arranges a dana or gift-giving ceremony, wherein he gives away most of his possessions. Upon leaving the capital city, a group of Brahmans request his horse-drawn chariot, which he willingly surrenders, whereupon Vessantara proceeds on foot with his wife and two children into the forest. As we might expect and as the logic of true dana requires, soon after Vessantara and his family are happily settled in their simple jungle hut, the prince is asked to give up his children to serve Jujaka, an elderly Brahman. When Indra appears in human disguise and Vessantara accedes to the god's demand that he surrender his wife, Maddi, the prince's trials come to an end. Having successfully met this ultimate test of generosity—the sacrifice of his wife and children—Vessantara's family is restored to him and he succeeds his father as king of Sivi.12

Whereas the Buddha story embodies the ideal of nibbana, the Vessantara story illustrates the doctrine of kamma, which in this instance is a reward for the meritorious act of generosity. Many Western scholars have focused attention on the differences between nibbanic or noble-path action and kammic-merit motivated action. But when these two types of action are placed within these two well-known narrative contexts, the interrelationships become more readily apparent. Both Siddhattha and Vessantara exemplify modes of selflessness symbolized respectively by a quest and a journey; renunciation marks the beginning of a critical threshold or testing period preceding a return or restoration. In the Buddha's case, the threshold state is one of intensive study and ascetical practice from which he emerges transformed as the Buddha. Vessantara's residence in the forest represents a testing ground from which he returns, not only to have his family and possessions restored, but also he is rewarded with an enhanced degree of royal power.

Even with their similarities, ...