![]()

SECTION 1

Painting, Seeing, Concepts

![]()

Gone, Missing

I am privileged, as it were, not only to dream about the specters of the night in all the helplessness and blind trust of sleep, but also at the same time to confront them in actuality with the calm judgment of the fully awake. … I long to say a last goodbye to everything up here, to go down into my burrow never to return again … [but] I find great difficulty in summoning the resolution to carry out the actual descent … without knowing what is happening behind my back and behind the door after it is fastened.

In the late summer of 1911, Franz Kafka lines up with thousands to see a blank square of empty wall, a patch of vacant white marked only by four iron pegs. A few miles away, Pablo Picasso stares up—with unblinking, half-seeing eyes reaching out from the side of his face—at the police who have taken him into custody. Kafka leaves the Louvre with his friend Max Brod and the two men make their way to the theatre, settle down in the darkness, their vision adjusting as they prepare to watch the five-minute film Nick Winter et le vol de la Joconde. Thrown together just a few days after the theft itself, the film satirizes what all of Paris has been talking about: someone has stolen the Mona Lisa.

The absence of da Vinci’s iconic work is news all across Europe. But not since Napoleon moved the painting into his private bedroom have the French, especially, pulled together to claim the woman with the strangely painted smile as legitimately their collective property. Now, though, the smile is like that of a Cheshire cat, faded from the wall, fading even from memory (see figure 1.1). They must go to the museum to not-see it once more. The Louvre, having shut down for a week as the criminal investigation began, agrees to re-open. Picasso is soon exonerated. (It was his friend, poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who, it turns out, had implicated the painter while being held in jail on suspicion of the theft. Apollinaire, no lover of “high art,” had recently called for the Louvre to be burned down. Only the police, it would seem, deem to take a poet at his word.) As the search continues for the true thief, attendance records at the Louvre are broken. Lines stretch out and around the museum with pilgrims coming to view the missing painting, shuffling past the empty spot on the wall in tears.

FIGURE 1.1. H. Peter Steeves. The Missing Mona Lisa. 2012. Photomontage.

They come to see the Mona Lisa knowing they cannot see it. As historian and curator Helen Rees Leahy will later explain it, “[they showed up] to gaze, overcome with emotion, at the blank space. … According to one newspaper, the crowds ‘contemplated at length the dusty space where the divine Mona Lisa had smiled. … It was even more interesting for them than if the Giaconda had been in its place.’ This was an understatement: the blank wall was the sensation of Paris, [as patrons] … filed past … and paid their respects to the emptiness.”

The thief, it turns out, does not share the Parisians’ sense of collective French ownership. But neither is he in it just for himself. Instead, Vincenzo Peruggia, a low-level Louvre employee, has stolen the Mona Lisa—at first hiding it in a broom closet and then simply walking out of the museum with the painting under his top coat—in order to return it to Italy where he feels it truly collectively belongs. In two years, Peruggia will be caught in Florence. And the Italians will agree to return the masterpiece to Paris—after, of course, first taking several months to exhibit it throughout Italy. They will also refuse to extradite the thief, praising him for his patriotism and giving him a minor punishment in the name of good border relations. The Mona Lisa will thus eventually be restored to the wall of the Louvre in 1913; and, having repeatedly come en masse to celebrate and see its absence for two years, patrons, less interested, will begin cutting back their trips to the museum. The curators and the marketing department will learn an important lesson: presence is sometimes overrated.

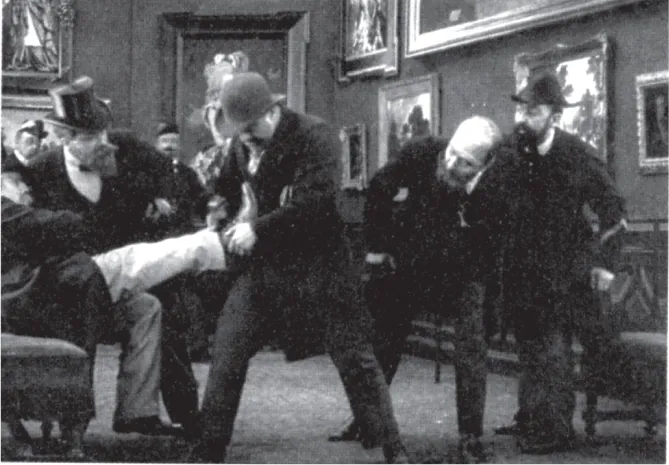

But tonight, Kafka and Brod sit in the dark, unable to see how the future will unfold. The film unspools and, like most films, presents something like a truth (see figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2. Still from the film Nick Winter et le vol de la Joconde [Nick Winter and the Theft of the Mona Lisa]. Dir. Paul Garbagni and Gérard Bourgeois. Pathé Frères, 1911. Bulletin Hebdomadaire Pathé Frères 34 (1911): N. pag.

Detective Nick Winter, stares at the blank spot on the wall where the painting used to hang, eventually turning around and noticing a shoe button on the ground. With this as his only clue, he disguises himself as a shoe-shiner, hoping no one will see his true identity. He begins stopping Parisians, forcing them to get their shoes shined in hopes of finding the thief—a man he imagines to be marked by the absence of a button. Unfortunately, the director of the Louvre, Monsieur Croumolle, is missing just such a button, and Winter mistakenly focuses all of his attention on the poor, innocent Croumolle. In the final moments of the film the museum is in turmoil; and though it is packed with people, no one notices—no one pays attention, no one sees—the thief sneak back in, replace the Mona Lisa, and steal away with Velazquez’s Princess instead, taking time to drop off a note that reads, simply: “Forgive me. I am nearsighted. I actually meant to take the painting beside it.”

This happened to me for the first time—unless I am blocking out all of the others, unless they are being blocked out, unless they have blocked themselves out—in the fall of 2000.

I had had a headache for three straight days. They were familiar to me at the time, nauseating and crippling, often moving me to tears and forcing me to retreat into a dark room. For as long as I can remember, I have preferred to be in dark spaces, even when my head was not hurting. I turn off as many lights as I can—always turning off all fluorescent lights—and work, see, and live with the dimmest of lamps after the sun goes down, which it always seems to have done no matter what time of day it is, since I refuse to open curtains and blinds at any hour, even covering most windows with dark, light-blocking fabric that gives the appearance of not so much stunting their ability to let in sun as obscuring the very fact of the windows, covering them over, pretending that they aren’t even possibly there. Living with me is not easy, I know. One has to appreciate burrowlike conditions. And this night, more than a dozen years ago, seemed like any other night to be in pain. The only light in my office was from my computer screen, and I was wishing that I did not have to ride the train home because I knew that there would be noise, the smell of bodies, people, but mostly light—far too much light.

Caught up in such worries, I noticed in that moment that I suddenly could not make out the lower portion of what I had been typing. The screen, it seemed, had simply disappeared there—not gone black, really, but rather somehow strangely become invisible. Before I could even panic—and this was surely a cause to panic for me as I have loved darkness but ironically feared blindness my entire life—something in the empty space took shape and began to look like a fat caterpillar, an organic squiggle of bright neon light that was pulsing yellow, gold, green, orange, white, with spirals of bright color twisting up the body like the moving stripes on a barbershop pole. The vivid light grew in intensity; and my fear grew, too, as I turned to look in a different direction, horrified to find that the caterpillar followed me, always staying in the same field of vision. It was not a part of the computer screen; it was a part of my seeing. When I closed my eyes to escape the creature, it stayed with me, growing in magnitude again in the complete black of my inner eye, like some sort of afterimage from having stared for hours directly into the filament of a now unseen light bulb. It was a part of me.

I did not know at the time how literally this was the case, as a scotoma of this nature is actually a visual manifestation of the firing of neurons located in the back of the head within the occipital cortex. I was, reluctantly, “seeing” the activity of my forebrain. And, of course, this act of seeing was itself an instance of brain activity with its own neuronal structure. The caterpillar not only twisted and warped in on itself but was premetamorphosed: it was, in some real sense, the biophysical manifestation of the act of seeing that I was seeing—not so much a noumenal appearance of a Kantian moment of engaging with the world, but a sort of aberrant Husserlian epoché, a reduction where noema and noesis were truly two sides of the same coin, two aspects of the same moment of consciousness. This is what it looks like to look at something. Tellingly, as my brain struggled to put that experience itself into something visual, it necessarily also manifested as a sort of blindness: what it means to see is to be blinded.

But that night, sitting in the dark, I understood and saw very little. More lepidopterist than phenomenologist, I did not know then that it was my own brain that squirmed in front of me, pinned down yet never for a moment under control. At the realization that I might never escape seeing it, I felt terror. Not only was I unable to see what was there in the world behind this thing, unable to see whatever it would possibly obscure for the rest of my life, but I also might never be able simply not to see it. Closing my eyes had only made it worse. And the realization that it might now always be on, always be visible—that it might take from me the ability to see only darkness—was overwhelming and worse, even, than the thought of being blind.

Within fifteen minutes it began to dim. Half an hour after it had first appeared, it was gone. It would not return, missing, for another year.

This happened to Matthew Girson for the first time—unless I am misremembering the story he told me several months ago, unless he is misremembering the story his mother told him because he was too young to remember it himself, unless she was misremembering what took place years ago, unless we are all somehow blocking out something—in the summer of 1970.

As a toddler, Matthew Girson went missing. His parents searched for him everywhere. He had been seen just moments before on the kitchen floor behind his mother, plain as a button, but now he was gone. Everyone knew that he was too small to have stumbled or crawled very far in such a short amount of time. The fact that he was not to be found in the house, each room empty, must have meant that, in the back of their minds, everyone was thinking the worst. As the search progressed they ran through the permutations of “gone”—lost, abducted, missing—until his mother heard laughter coming from her bedroom. Underneath the bed, pressed up against the back wall in an impossible way in such a small space, Matthew Girson sat, covered in a blanket, laughing in his own dark world.

Within fifteen minutes he had been found. He would not go missing again for another year.

Memoirs of the Blind is one of Derrida’s most personal works, though his person is always visible throughout all of his work, of course. Here he tells the story—or at least the narrator tells the story—of a youthful infatuation with drawing and the way in which his brother’s talent, far greater and receiving more familial praise, drove Derrida to turn to words rather than lines in order to create. After recalling his failure to copy his brother’s copies of family photographs—after admitting to something of a fratricidal desire—Derrida writes:

I have never in my life drawn again, not even tried. Except once last winter—and I still keep the archive of this disaster—when the desire, and the temptation, came over me to sketch my mother’s profile as I watched over her in her hospital bed. Bedridden for a year, surviving between life and death, almost walled up within the silence of this lethargy, she no longer recognizes me, her eyes veiled by cataracts. We can only hypothesize about the degree to which she sees, about what shadows pass before her, whether she sees herself dying or not.

Derrida has been slipping in and out of tenses, seeing and not seeing, and speaking of childish things. Not only his own boyhood memories, memories that Freud will tell us are always on the verge of being unseen, but of being a child even when one is older. Always a child before one’s mother’s eyes, seeing or not. A child who asks philosophical questions about art: “The child within me wonders: how can one claim to look at both a model and the lines [traits] that one jealously dedicates with one’s own hand to the thing itself? Doesn’t one have to be blind to one or the other? Doesn’t one always have to be content with the memory of the other? The experience of this shameful infirmity comes right out of a family romance.” This is where Derrida tells the story of his brother, a story I omit here only to point out that jealousy and copying are already at work in Derrida’s text before he gets to thinking about the relationship between art and being seen by one’s mother, between what is hidden in aesthetics and what is hidden in the family.

The child within Derrida is asking whether or not all drawing is founded on blindness, and thus if all seeing is as well. The worry is most clearly seen if we focus on the self-portrait, but it is there with all drawing and painting in general.

If I turn to look into a mirror in order to see myself in order to paint myself, I must study what I find in the mirror—an image of myself—but then I must turn my gaze to the canvas as I make the marks there that will represent what I see. To be more precise, though, we should not say “the marks that will represent what I see” but rather “the marks that will represent what I have seen” since at this particular moment of painting I am necessarily no longer seeing the image of myself in the mirror but I am, instead, now looking elsewhere. I am seeing the marks I am making on the canvas. As I make those marks, I am seei...