![]()

Part I

Institutions

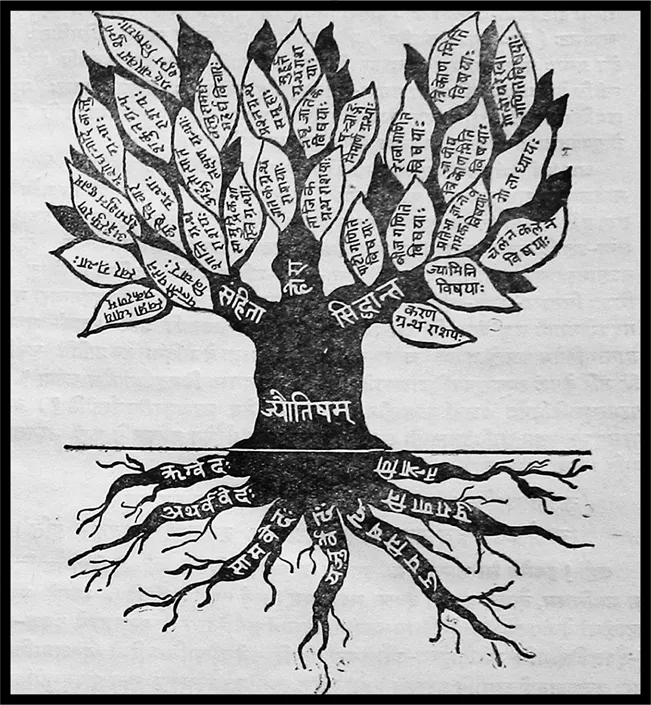

Figure 2. The jyotiṣa tree and its branches. Illustration taken from the Jātakapārijāta of Vaidyanātha, a Sanskrit treatise on natal horoscopy (Chaudhary 1953, 3).

The roots of the jyotiṣa tree are (from left to right): the Ṛgveda, the Atharvaveda, the Sāmaveda, the Yajurveda, the Upaniṣads, the Purāṇas, and the Tantras. The jyotiṣa trunk develops into three branches (from left to right): saṃhitā (divination), horā (horoscopy), and siddhānta (astronomy and mathematics). The leaves on each branch are divided into the following:

Saṃhitā:

Treatises on breath (svara-granthāḥ).

Discussion of oneirology (svapna-adhyāya-prakaraṇam).

Examination of falling lizards (palli-patana-vicāraḥ).

Treatises on predicting rain (vṛṣṭi-vicāra-granthāḥ).

Effects of good or evil omens as a result of trembling in different parts of the body (aṅga-sphuraṇa-śubha-aśubhaṃ phalaṃ).

Treatises on the examination of earth, sites, buildings, and so on (bhū-śodhanādi-vāstu-granthāḥ).

Collections of treatises on appeasement rituals (śānti-grantha-rāśayaḥ).

Collections of treatises on presages (śakuna-grantha-rāśayaḥ).

Study of the auspicious and inauspicious influence of the movement of the planets (graha-cāra-vaśa-śubha-aśubha-viṣayāḥ).

Treatises on signs, presages, and marvels (adbhuta-utpāta-lakṣaṇa-granthāḥ).

Treatises on physiognomy (sāmudrika-śāstri-granthāḥ).

Study of the cost of cheap and expensive substances (vastu-samargha-mahārgha-vicāraḥ).

Horā:

Collections of treatises on natal horoscopy (jātaka-grantha-rāśayaḥ).

Collections of treatises on the Perso-Arabic art of casting horoscopes (tājika-grantha-rāśayaḥ).

Compilation of treatises on the horoscopy of queries (praśna-grantha-samūhā).

Collection of horoscopy treatises on auspicious moments (muhūrta-grantha-rāśayaḥ).

Studies of lost birth horoscopes (naṣṭa-jātaka-viṣayāḥ).

Treatises on the composition of almanacs (pañcāṅga-nirmāṇa-granthāḥ).

Siddhānta:

Collections of concise astronomical manuals (karaṇa-grantha-rāśayaḥ).

Study of the “bowstring” or the sine (jyām-iti viṣayāḥ).

Algebraic studies (bīja-gaṇita-viṣayāḥ).

Studies of differential calculus (calana-kalana viṣayāḥ).

Studies of arithmetic (pāṭi-gaṇita-viṣayāḥ).

Studies of “arc trigonometry” (cāpīya-trikoṇam-iti viṣayāḥ).

Geometrical studies (rekhā-gaṇita-viṣayāḥ).

Lessons on the spheres (gola-adhyāyaḥ).

Studies of “triangles” (trikoṇam-iti viṣayāḥ).

Studies of the geometry of the spheres (golīya-rekhā-gaṇita-viṣayāḥ).

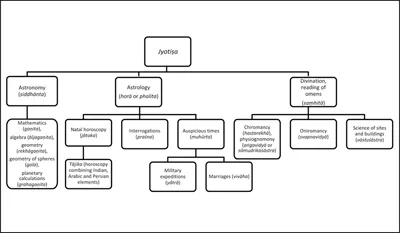

Figure 3. The divisions of the astral discipline. Figure by the author.

![]()

1

The Many Branches of a Tree

Jyotiṣa as a Scholarly Tradition

Ideas are to objects as constellations are to stars.

—Walter Benjamin

For someone not familiar with jyotiṣa, it may be difficult to think together subjects as different as lunar eclipses, the shape of an elephant’s feet, trigonometric calculations, the preparation of a perfume, the theory of planetary aspects, the eruption of rashes on a person’s skin, the sexagesimal division of temporal units, and lizards falling. This list may rather remind the reader of the famous Borgesian classification purportedly found in a certain Chinese encyclopedia entitled Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge (Borges 1942) and cited by Foucault as an example of a taxonomy “breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things” (Foucault 1970 [1966], xv). According to standard academic categories of knowledge, these different subjects fall within the competence of disciplines as far removed as astronomy, zoology, mathematics, cosmetology, astrology, or medicine. Nonetheless, in Sanskrit literature these subjects are investigated within a single discipline, jyotiṣa, and are described and studied within a literary corpus designed as jyotiḥśāstra. The first part of this research intends to examine how, despite the variety of subjects dealt with and the diversity of investigative methods employed, jyotiṣa developed over time and continues to be practiced today as a discipline. As we will see, the epistemological identity of jyotiṣa is expressed in Sanskrit through terms such as aṅga, vidyā, śāstra, vijñāna that are used, at different periods and in different contexts, to refer to jyotiṣa as an authoritative form of knowledge.

While, in most studies conducted by Sanskrit scholars, astral sciences and other scholarly traditions are approached as “knowledge systems” (Pollock 2008), here we choose to look at jyotiṣa as a “discipline,” a category that has a specific analytical fecundity for our study. To start with, the idea of discipline highlights the institutionalized, standardized, and normative dimension of knowledge, more than its theoretical coherence or systematicity; second, this idea makes it possible to articulate the intellectual, institutional, and social aspects of knowledge around a single axis, thus connecting materials as diverse as textual sources, historical documents, and ethnographic data.

The three chapters that make up the first part of this book will consider jyotiṣa, respectively, as a theoretical discipline described in Sanskrit literature (chap. 1), as an academic discipline taught at universities (chap. 2), and as a professional discipline practiced by specialists (chap. 3). These three dimensions of the astral discipline should be viewed conjointly. As we shall see, while on the one hand the theoretical complexity of jyotiṣa, as it is formulated in the texts, impacts its social implementation, on the other hand, institutional settings and social configurations define the validity of the discipline on the basis of constantly changing criteria and thus affect the manner in which the texts are written, read, and interpreted.

Furthermore, to approach jyotiṣa as a discipline implies not viewing it as an isolated subject, circumscribed by impermeable borders. Even if, as Christopher Minkowski observes, “Jyotiṣ was practiced at some remove—in method, assumptions, even in the form of textuality—from the pre-eminent śāstras, the sciences of language analysis (vyākaraṇa), hermeneutics (mīmāṃsā), logic-epistemology (nyāya), and moral-legal-political discourse (dharmaśāstra)” (2002, 495), it is also true that the astral sciences developed historically and continue to be practiced today in dynamic interaction with ritual, devotional, medical, and architectural ideas. The interdependency between jyotiṣa and these fields of knowledge exists both at the conceptual and the operational levels. The first type of interdependency is attested by the existence of numerous technical concepts that, despite their semantic variations, substantially connect astral sciences with other areas of thought. One only needs to mention the concepts of graha, doṣa, yoga, or ariṣṭa that play a crucial role not only in astrological but also in medical, tantric, and devotional literature, although their meaning varies from one field to another. A functional interdependency is explicitly formulated in the texts as, from the outset, jyotiṣa was envisaged as a pragmatic discipline to ensure the success of ritual, therapeutic, or agricultural activities. The representation and worship of planetary deities is also an “interdisciplinary” subject described not only in astrological treatises but also in iconographic, ritual, devotional, and tantric literature.

David Pingree’s monumental work (1970–1994) of classifying, identifying, and dating astral literature, and his critical editions of the Yavanajātaka (Pingree 1978a; YJ) and the Vṛddhayavanajātaka (Pingree 1976), represent a valuable starting point for the history of jyotiḥśāstra in India. These studies allow us not only to situate the Sanskrit astrological texts in relation to each other, but also to understand their development in the light of the exchanges between different civilizations. Few areas of the history of knowledge show, as jyotiṣa does, such a wealth of intellectual exchanges between Babylonian, Greek, Latin, Arabic, Persian, and Sanskrit sources. In India as elsewhere, this form of knowledge develops over a long process of borrowing, translations, and interpretations that Pingree’s invaluable research allows us to follow in all its details. Nonetheless, as Francis Zimmermann remarks in his review of Pingree’s critical edition of the YJ (1978a), “in this commentary the internal comparisons of Sanskrit literature are subordinated to the external comparison between India and its neighbours. … [The] analysis of the Sanskrit terms in their Sanskrit context is somewhat sacrificed to the search for sources and borrowings” (Zimmermann 1981, 300). By describing the impact of stereotyped nomenclatures of Ayurvedic medicine on the classification system established in the horoscopy treatises, Zimmermann (1981) opens up a research path that has been little explored since, which consists of studying the interactions between literature on the planets and other domains of knowledge found in Sanskrit literature. In the wake of this research, rather than underscoring the borrowing of external elements, the present work is more interested in the “local” anchorage of astrological knowledge, or its cultural and social rootedness in the South Asian region.

The exchanges with ritual, medical, and cosmological systems of knowledge are of particular interest to us here as a means to understand the criteria that support the intellectual legitimacy of the astral discipline. In both ancient texts and contemporary debates this legitimacy is most often based not only on criteria that exist within the discipline, like the respect for textual authority, but also on the relationship—of complementarity, contradiction, or reciprocal influence—between jyotiṣa and other forms of knowledge accepted as valid or true. We will see that as early as the first centuries of our era, the authors of treatises on the art of casting horoscopes (jātakaśāstra) attempt to reconcile the theory of planetary influences with another Brahmanical doctrine that serves to explain human destiny, the theory of karma (chap. 5). About jyotiṣa and Purāṇas, Minkowski has shown that the question of compatibility (avirodha) or incompatibility (virodha) between the models of the cosmos described in the astronomical treatises (siddhānta) and the cosmology of the Purāṇas raised questions for the authors of the early modern period and was vividly debated during the modern period (Minkowski 2001 and 2002...