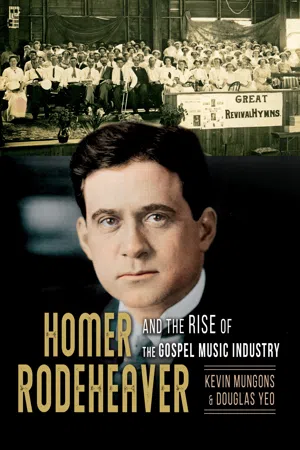

![]()

1

PROLOGUE

ATLANTA 1917

Fifteen thousand singers filled the revival tabernacle with an old hymn, waves of sound pouring from a proud sea of African American voices. As the verses were lifted up, each stronger than the last, Homer Rodeheaver gestured from the platform with broad, sweeping motions. Everyone—everyone—sang.

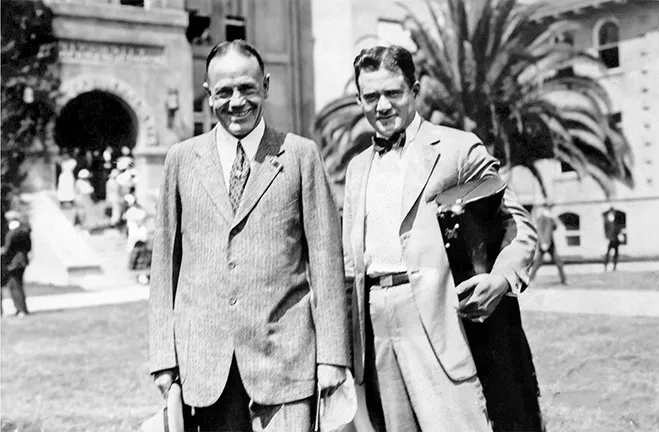

FIGURE 1.1. Billy Sunday and Homer Rodeheaver in Los Angeles in 1917, just before the Atlanta revivals. Courtesy of Morgan Library, Grace College, Winona Lake.

Was it his impish good looks or the freshly pressed linen suit? Perhaps the infectious chorus he blew from his gold-plated trombone? Or was Rodeheaver’s theory correct, that something more basic commanded this attention—the power of gospel music to unite the most diverse audiences? Rodeheaver had been anticipating this particular Atlanta meeting as a way to test his ideas about the universal appeal of gospel songs, those congregational testimonies that were forged from diverse American musical influences. While later generations would speak of Black gospel or white gospel or southern gospel, Rodeheaver didn’t live in such categories. To his way of thinking, a good gospel song would unite any audience, even audiences fragmented by racial tension.

He started the service on common ground, leading everyone in “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” which he added to the tabernacle repertoire after World War I broke out in April. The construction crew had draped the Atlanta platform with flags, and Billy Sunday would spike his sermon with slam-bang attacks on the godless Kaiser and Huns. Like politicians throwing out easy applause lines, the revivalists knew how to provoke a chorus of Amens. Rodeheaver’s motivation for choosing a patriotic song seemed pretty obvious. A thousand African American soldiers were sitting tall in their khaki uniforms, right in front of him, visiting from nearby Camp Gordon.

By the time the audience reached the end of the first stanza, a group of late-arriving journalists hurried to the row of desks reserved at the front. Rodeheaver was starting the service a half-hour early again. The tabernacle filled up quickly, just like the first ten days of meetings when organizers enforced a whites-only attendance policy. Thanks to Sunday’s friendly attitude toward reporters, the Atlanta Constitution had been running Billy Sunday news on the front page, right next to its war coverage. One reporter took shorthand during the sermon, which was transcribed and printed verbatim by the next morning. Another Constitution reporter—usually assigned to theater and vaudeville—covered the tabernacle music just like a concert review. Every other local paper sent reporters, too, along with the Atlanta Independent, a Black-owned paper that had fearlessly called the segregated meetings a religious affirmation of Jim Crow.

Professionally jaded but smart enough to ride a populist trend, the reporters ended up writing positive stories, lots of stories. But now, just when they thought their nightly revival beat was becoming routine, something new drew the journalists back to their seats. Rodeheaver had started the service with the same patriotic song the reporters had heard from the white audiences. Now the Black congregation was singing the same words with a different meaning, warming up to a full roar on the final line: “Let freedom ring!”

Not waiting for the echo to die down, Rodeheaver waved his accompanists into a familiar hymn. He had arranged two grand pianos in front of the platform and pulled the lids off for maximum volume. George Ashley Brewster and Bob Matthews sat side by side, dueling pianists who could be heard above any crowd. The news reporters, accustomed to staid church music played on a pump organ, didn’t quite know how to describe what they saw.

“Brewster literally fights the keys, bringing out the harmony in great thunderous chords, while Matthews’s hands run up and down the keyboard of the other piano in ragtime accompaniment,” said Ned McIntosh, the arts reporter. But another reporter for the Constitution claimed just the opposite: “They struck up ’Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing,’ and romped off toward the home plate. Brewster played the ragtime version, and Matthews injected the classical technique.”

Perhaps one of the players was trying to fuse traditional church music with ragtime? Maybe, but no one could tell for sure. No one had heard anything like it.

“I’ve seen Toscanini direct an army of musicians without a score; I’ve seen Damrosch do his doggonedest; I’ve listened to jazz bands and have heard Irving Berlin’s wildest creations,” claimed McIntosh. “But when Ashley Brewster and Bob Matthews begin to fight the ivory out at Billy Sunday’s big meetin’, I wouldn’t swap my seat for a ticket to anything I ever heard of. And did it sound sacrilegious? Not on your life. It was thrilling, contagious, infectious.

“It compelled you to sing.”

* * *

By this point, Sunday and Rodeheaver had been traveling the revival meeting circuit for eight years. Reporters gave Rodeheaver a good deal of credit for Sunday’s success. Both of them had adopted stage personas that seemed close to their own personalities: Sunday was a rough-hewn former baseball player with a flair for slang-filled oratory, a hellfire-and-brimstone theatrical force who could hold a crowd’s attention even if the sermon stretched to two hours. Rodeheaver was the suave, joke-cracking sidekick, a one-man vaudeville show who was happy to provide the opening act. On any given night, Sunday and Rodeheaver offered the best show in town—and free.

Offstage, Sunday struck many as introverted, even aloof, but he could turn on the charm when surrounded by reporters or celebrities. Rodeheaver never worried about turning on the charm—he was charming, a larger-than-life personality who lit up the tabernacle as soon as he mounted the platform steps. Just before dinner he would change from his day clothes into a custom-tailored business suit with a contrasting vest; a white, round-collared shirt; and a silk four-in-hand tie. His pants were hemmed fashionably high, revealing calfskin shoes covered by gray spats. Billy Sunday dressed the same way. Neither one looked like a preacher; both tried to project the image of successful, stylish businessmen.

At thirty-seven, Rodeheaver was an eligible bachelor, five feet, eight and one-half inches tall, barrel-chested, with wavy brown hair and brown eyes. He would have been a fine catch for a chorus girl or a preacher’s daughter. But after suffering a public breakup with Georgia Jay in 1914 (she sued him for $50,000), Rodeheaver seemed unlikely to take the plunge anytime soon. He flirted from the podium and otherwise seemed achingly inaccessible. A few days earlier, the Atlanta Constitution had reported how Rodeheaver created “quite a fluttering among the feminine hearts” when he deliberately leaked a few personal details to his audience.

“I have a wife and two children to support,” he said, expertly waiting a beat for the soft sighs before continuing with his explanation. The wife and two children were not his—they were the wife and children of his late father. Rodeheaver used the tease as a way of introducing his stepmother, Bettie Rodeheaver, who had traveled from Roanoke, Virginia, for the evening service. And behind the scenes, Homer Rodeheaver did exactly what he claimed, sending support checks and eventually moving his stepfamily to Winona Lake, Indiana, his home base.

As affable as Rodeheaver seemed onstage, nothing was quite as effortless as it appeared from the pine benches that lined the sawdust trail. Rodeheaver had tamed his Tennessee twang through voice and diction lessons, had played trombone in an army band, and had studied choral conducting. After honing his platform presence through years of Chautauqua appearances, he aggressively tested a revival format programmed to bring spiritual results. He recruited the best musicians—Sunday paid them as much as Sousa paid his band members. And Rodeheaver’s publishing company cultivated the best gospel songwriters. Given his personal drive and effervescent personality, Rodeheaver would have succeeded on the vaudeville stage, had he been so inclined.

And yes, the critics quickly made that connection. A few months earlier, a group of liberal Boston clerics had attacked Sunday as the “vaudeville revivalist,” but nearly everyone understood who, exactly, was creating the vaudeville atmosphere. Fueled with an endless supply of songs, magic tricks, and stand-up comedy, Rodeheaver’s warm-up act was getting great reviews. Theater ticket sales plunged as audiences flocked to the revival tabernacle instead. One victim was Al Jolson, who tried to counter sagging attendance by adding another act to his vaudeville lineup, a wicked parody of Billy Sunday and revivalism. “When Sunday comes to town, I hear that he’ll save women, free,” sang Jolson, clowning and mimicking Sunday before landing the punch line: “I hope he saves a blonde for me!”

Jolson even planted a group of costumed chorus girls at the back of the revival tabernacle, irreverently instructing them to go forward when Billy Sunday called for sinners to hit the sawdust trail. Jolson figured that if he poked at Sunday a few times, his Broadway troupe might earn a public condemnation, money in the bank for any entertainer.

But Jolson was no match for Rodeheaver when it came to publicity stunts. When Jolson’s chorus girls had an afternoon off, Rodeheaver upped the ante by inviting them to sing at the Boston tabernacle. Of course they said yes (Rodeheaver hadn’t lost his touch), leading to the spectacle of “Don’t Leave Me, Daddy” one night and “Brighten the Corner” the next afternoon. Jolson loved it—the resulting flap gave his musical revue a fresh blast of publicity, and his ticket sales recovered.

Rodeheaver was never worried. By sharing the spotlight, he had primed Jolson for a quiet visit the next morning. Mr. Sunday would be grateful if you stopped mentioning him in your fine show, Rodeheaver suggested, ever unctuous. Jolson immediately agreed.

Homer Rodeheaver had become more than a warm-up act. Everything he did was calculated to generate publicity, following a careful sequence to create audience participation. Any audience.

* * *

“Not before in the history of the South, perhaps, have so many Negroes been gathered together for a meeting of any sort,” reported the Atlanta Constitution. “Through a natural inclination and the urgings of Rody, no such harmony has ever been heard in the south, or probably in any other man’s neck of the woods.”

But all this talk of “harmony” from white journalists obscured the controversy of the 1917 Atlanta revival. Until now, Sunday and Rodeheaver’s fame had been limited to northern cities. After a string of successes in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, their Atlanta invitation came with a huge condition from the local ministerial association: the meetings would be segregated. Billy Sunday wanted the Atlanta meetings badly enough that he accepted the ground rules. To his way of thinking, his mission was to preach the gospel, even if that required an affirmation of southern status quo. Like most of Atlanta’s leadership, the white ministers saw themselves as progressive, believing Atlanta to be a model city in the New South. Black pastors were less convinced. They wanted the Sunday meetings, too, but they were weary of the imposed social order. The ongoing tension would severely test Sunday and Rodeheaver’s loose coalition of Protestants.

When fire swept through Atlanta five months earlier, it was no respecter of persons, destroying 300 blocks of Black and white neighborhoods, including churches of every denomination. Firefighters finally contained the blaze by dynamiting a row of old-money mansions; even the rich suffered loss. But recovery efforts were less democratic. By the time the Sunday party rolled into town that November, Atlanta was selectively rebuilding white neighborhoods, using the tragedy as another excuse to isolate Blacks into the Old Fourth Ward.

The U.S. Army opened Camp Gordon in July, planning a boot camp where blacks and whites would train together before marching on to war. Then the Commission on Training Camp Activities segregated all recreational activities, resulting in precious little social territory for the African American troops. A deeper problem emerged as the local draft board registered every eligible male, feigning equality, but turned around and granted exceptions to 85 percent of Atlanta’s whites. Meanwhile, only three percent of Blacks were excused. The New South looked suspiciously like the old.

During preparations for the Atlanta meetings, Billy Sunday freely admitted that he had not spent much time in the South, nor had he spent much time around Blacks. In fact, his sermon on November 19 would be the first time he had preached to a large crowd of African Americans. Rodeheaver, on the other hand, grew up in the racially mixed environment of eastern Tennessee. He absorbed the Black musical tradition more directly.

“The songs of my earliest recollection were the songs the Negro boys sang to my mother in the mountains of East Tennessee,” he later wrote. “I not only grew up in the atmosphere of the Negro spiritual but their songs were part of my life. Then too the Negro boys would sing spirituals to me while I, in turn, would sing to them the gospel songs.” Rodeheaver absorbed the southern tradition, the whole complicated lot of it, including the folk songs of rural whites. “I sang the mountain ballads and won many a prize for singing them at picnics, playing the harmonica from an improvised holder while I picked the melody on the guitar,” he recalled, but he still expressed preference for the spirituals.

Right from the start, Rodeheaver’s music would defy easy categorization. Surrounded by a wide variety of influences early in life, he never wasted much energy trying to sort them out. All of this music, whatever its source, belonged to his broad definition of gospel music.

For two weeks prior to that night’s meeting, Rodeheaver had spent his mornings visiting Atlanta’s Black colleges—Clark, Morehouse, Morris Brown, and Spelman—persuading them to combine their choirs for a spectacular tabernacle concert. To this core he added the best choirs from Atlanta’s Black churches. On the evening of the Sunday meeting, the choir arrived early for a single rehearsal. In spite of their limited preparation, the hastily assembled choir performed without printed music. These songs were rarely written down—perhaps couldn’t be written down in any way that would capture their full glory. The singers knew them by heart.

Rodeheaver’s plan to showcase African American music was by no means new. First Congregational Church began hosting the Atlanta Colored Music Festival in 1910, an annual event that featured college choirs, solos by Harry T. Burleigh, and spirituals sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers. When...