![]()

To Seek Fortune Elsewhere

CHAPTER ONE

January – June 1777

As the calendar turned from 1776 to 1777, Washington’s army was ensconced within the highlands of New Jersey, monitoring the British forces. The British were wintering in upper New Jersey, burrowed into the metropolis of New York City and blanketing the surrounding New York boroughs.

Washington had his army snuggled behind the Watchung Mountains around Morristown, New Jersey, a winter encampment “best calculated of any in this Quarter [of the country] to accomodate and refresh them.” By May 1777, Washington’s wish of having a respite and reinforcements for his army seemed to have been granted. The Continental army that marched into Morristown on January 6 numbered approximately 2,500 men. Five months later, on May 20, the return for the army showed 38 regiments numbering 8,188 men, with the majority recruited and enlisted for three years or the duration of the war, something Washington had eagerly been pressing upon the Continental Congress and various state governments for a long time.

Around this time Maj. Gen. Henry Knox, Washington’s artillery chief, wrote to his wife with an air of hopefulness: “[I]t appears America will have much more reason to hope for a successful campaign the ensuing summer than she had the last.” Arriving from France at this time were much-needed military supplies, including 1,000 barrels of powder, 11,000 gunflints (needed to ignite the firelock of a musket), and even more importantly, 22,000 muskets.

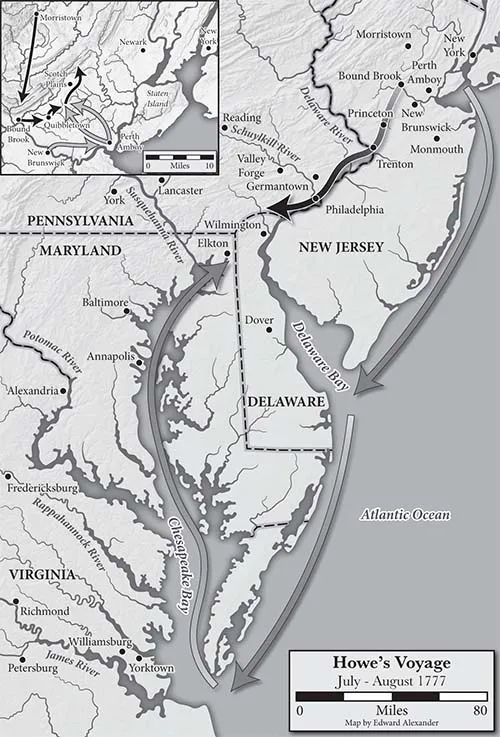

HOWE’S VOYAGE—After being unsuccessful in bringing George Washington’s army to battle in New Jersey, Howe embarked his forces for a voyage south, eventually landing on the banks of the Chesapeake Bay and changing the theater of operations for the final months of the campaigning season of 1777. In the ensuing campaign he would successfully capture Philadelphia, the American capital, but ultimately hurt the broader British war effort. (Dark line - Washington’s forces / Light line - British)

British ships of war, similar to the one in this painting, transported Howe’s army to Maryland. (nypl)

Eight days after receiving the returns for the army, Washington moved his rejuvenated command, marching them 20 miles to the southeast near Bound Brook in the Middlebrook Valley, behind the First Watchung Mountain, the southern of the two Watchung Mountains in the range. Here they were only eight miles from New Brunswick, where a portion of the British army was wintered.

On Friday, June 13, 1777, the behemoth British and German force, numbering 17,000 men, stirred from their winter cantonment. What was transpiring in British-held New York City, with the construction of boats and then transporting them on wagons, suggested Howe’s intention to march across New Jersey to strike at the American capital of Philadelphia, a target that the previous December Howe had called off, after Washington’s sudden strike at Trenton and follow-up in January at Princeton.

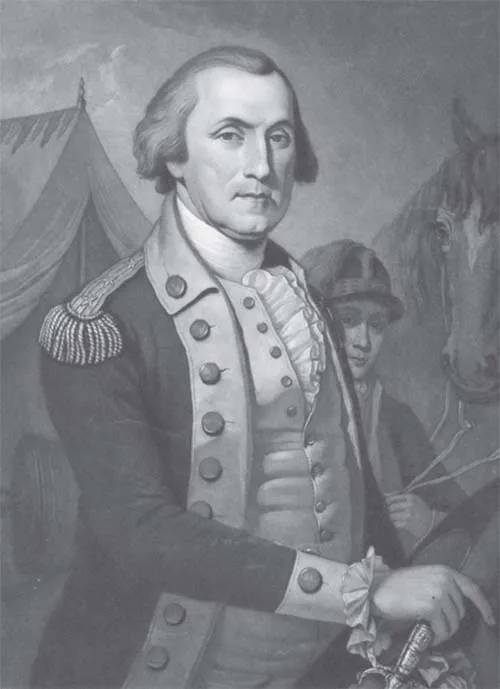

John Sartain painted this likeness of George Washington in 1850, copied from an earlier likeness painted by James Peale. (yale)

Speculation from both British and American officers and soldiers ran rampant. Washington fully believed that Howe intended to push straight forward through New Jersey in an all-out effort to capture Philadelphia. Captain Friedrich von Munchhausen, of Howe’s staff, believed the second day of campaigning, June 14, would see a surprise pre-dawn strike intended to destroy a 2,000-man force at Princeton under American Gen. John Sullivan.

Lord Richard Howe, whose nickname was “Black Dick” because of his dark complexion, was brother to Sir William Howe and in charge of transporting the army. (nypl)

Yet when daylight came on June 14, the action sputtered along with no sense of urgency on the part of the British. In fact, the exact opposite occurred: the British army set up an encampment, a sign contradictory to active campaigning. Or in the words of General Knox, “their conduct [the British] was perplexing.” If Sir William Howe was trying to entice the Virginian out of his hillside enclave, he was sorely mistaken, as “Washington is a devil of a fellow, he is back again, in his old position, in the high fortified hills” and did not seem inclined to come down. Even Sullivan’s forces had retreated to higher ground from Princeton.

For the next few days, this is exactly where the two forces remained: Howe’s men behind temporary earthworks, or redoubts, built around Middlebrook, New Jersey, staring out at Washington’s forces positioned in the hillsides of the Watchung Mountains. Skirmishing had been the staple of the preceding days. Since the campaign had opened, the British had not advanced 10 miles, and as June 18, 1777, melted into the history books, both sides geared up for more skirmishing and attempting to discern the other’s true intentions. However, as the sun rose the next day, the British army moved, but did not advance, instead retracing its steps to New Brunswick. Three days later the British evacuated New Brunswick.

A view from the overlook toward the Elk River. Imagine approximately 250-300 wooden vessels in the water at the top of the image. (psg)

A view back down the Elk River from higher up on the bluff. Ships would have filled the waterway, showing the true might of the British navy in North America. (psg)

The British crossed the Raritan River and marched eastward to Perth Amboy with Washington’s forces following. Advance attachments, infantry under Gen. Anthony Wayne and Col. Daniel Morgan’s riflemen, struck the British rearguard on the Quibbletown Road and at Moncrieff’s Bridge. Although it looked like the British were retreating, the wily Howe had accomplished one objective: coaxing Washington out of the highlands and into the more open terrain of central New Jersey.

A sketch of a Hessian soldier, from the time period in which these German mercenaries would have been in the employ of the British crown. (nypl)

At Paoli, the Paoli Grave Site occupies ground that saw the largest concentration of American dead and wounded. The day after the battle, a farmer, Joseph Cox, made his way to the battlefield and began the interment of “52 brave fellows … bury’d… next day,” although that number would increase by one when the monument was erected in 1817. (psg)

![]()

Obliged to leave the Enemy Masters of the Field

CHAPTER TWO

August – September 1777

“For my part, I must say, I would not wish to move until we know with a certainty where the Enemy Intend operating, as we have Certainly for some time past been Marching and Counter Marching to very little purpose” was how one Pennsylvania militiaman explained the current actions of American forces in August 1777. Fellow officers would have agreed with this sentiment, as Howe’s army had disappeared into the blue of the Atlantic Ocean.

When the British finally came ashore in northern Maryland, Washington’s army was near Philadelphia, having moved to the suburb of Germantown and now encamped along Neshaminy Creek. With news quickly arriving of the British whereabouts, Washington realized that this bit of good news was tempered by the stark realization that no defenses had been constructed between the enemy and Philadelphia. Yet, if he could get to one of the creeks that traversed southeastern Pennsylvania, it could provide an impediment to Howe’s approach and force an engagement on his terms.

Washington had to both move his men quickly and also put up a brave front for the citizenry and the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, so he marched his 11,000-man army, with accompanying artillery and cavalry, through the streets of Philadelphia toward the eventual battlefield at Brandywine.

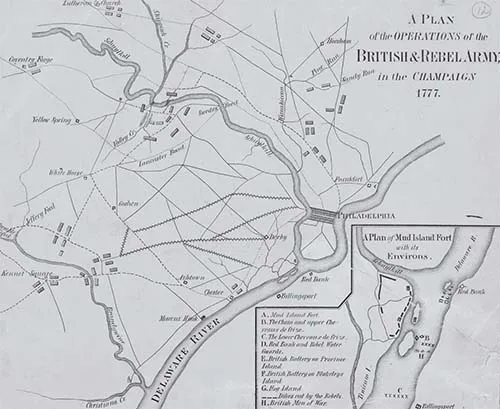

A historic map of the campaign of 1778 shows the operations of the British. It lists the Continental army as the “rebels,” which shows the political leanings of the mapmaker. (nypl)

By early September both forces converged around the area of Brandywine Creek, and skirmishing increased as each side tried to locate the other’s main force. On September 9, a heavy skirmish erupted at Cooch’s Bridge, Delaware. The next day, Howe was at Kennett Square, 10 miles from Washington’s army, which was centered on Chadds Ford.

Howe chose to conduct the coming engagement in his signature style, by ushering in a flanking movement while distracting Washington with diversionary preparations in his immediate front. What ensued on that Thursday was the largest engagement per total of combatants involved, during the entire American Revolutionary War.

Leading a column up the road from Kennett Square, Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen made contact with American troops a few miles from Brandywine Creek. The sparring continued as the American light troops, under Gen. William Maxwell, slowly gave way, the combined British regulars and hired German troops advancing to the creek itself.

Meanwhile, the main British column, with Howe in tow, made a 17-mile, nine-hour march, crossing to the northwest of the American line and appearing on their flank in the early afternoon. Around 4...