![]()

Chapter 1

‘How many divisions has the Pope?’

They were discussing the Pope. ‘Let’s make him our ally,’ proposed Churchill. All right, smiled Stalin […] ‘How many divisions has the Pope? If he tells us … let him become our ally.’1

In deciding to enter the war against Japan, the Soviet government took into account, first of all, that imperialist Japan in the Second World War was an ally of fascist Germany and provided the latter with constant assistance in its war against the USSR […] thus the war against imperialist Japan was a logical continuation of the Great Patriotic War for the Soviet Union.2

When the ‘Big Three’ - Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin - met at Yalta for the Argonaut Conference from 4 to 11 February 1945, the defeat of Nazi Germany was plainly imminent. American, British, Canadian and French armies were advancing on Germany’s western border and had defeated the Ardennes counteroffensive (‘The Battle of the Bulge’). Situated along the Rhine, from north to south, were the 21st Army Group (Canadian First Army and British Second Army), the 12th Army Group (US First Army, US Third Army, US Ninth Army, and US Fifteenth Army) and the 6th Army Group (US Seventh Army and French First Army). Along with their integrated Tactical Air Forces, they were poised before the supposedly impregnable West Wall (‘Siegfried Line’) ready to invade Germany itself. In Eastern Europe several massive Red Army Fronts (more or less equivalent to reinforced Anglo-American army groups) were only around 130km from Vienna, 190km from Prague and some 70km from Berlin. Though there was still some fearsome fighting to come, for Hitler, who on 16 January had moved into his bunker, from which he was fated never to emerge, the end was most definitely nigh.

This was far from the case with respect to the other member of the Axis. Though the Imperial Japanese Navy had ceased to be a factor in the war’s outcome, and the American unrestricted submarine campaign had imposed a virtual blockade on Japan itself, the Japanese Army was considered a formidable military force. Roosevelt wanted Soviet assistance in defeating it. At a bilateral meeting on 8 February 1945, with Averell Harriman, the US Ambassador to the Soviet Union, and Vyacheslav Molotov, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs (Soviet foreign minister), in attendance, Roosevelt discussed the matter with Stalin.3

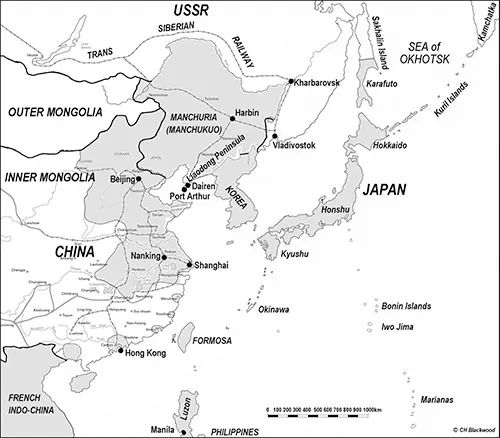

East Asia and Japan. The shaded portions show Japanese (or Japanese-controlled) territory. (© Charles Blackwood )

The President said that with the fall of Manila4 the war in the Pacific was entering into a new phase and that we hoped to establish bases on the Bonins and on the islands near Formosa. He said the time had come to make plans for additional bombing of Japan. He hoped that it would not be necessary actually to invade the Japanese islands and would do so only if absolutely necessary. The Japanese had 4,000,000 men in their army and he hoped by intensive bombing to be able to destroy Japan and its army and thus save American lives.5

He was, of course, acting on the advice of the joint chiefs of staff, who had sent him a pre-conference memorandum on the matter outlining the ‘basic principles in working toward USSR entry into the war against Japan’. First among these was ‘Russia’s entry at as early a date as possible consistent with her ability to engage in offensive operations is necessary to provide maximum assistance to our Pacific operations.’6

Stalin, who ‘held most of the military cards at Yalta’ and knew it, was naturally enough receptive to Roosevelt’s blandishments:7 he had publicly denounced Japan as an ‘aggressor nation’ on 6 November 1944.8 Indeed, he had agreed in principle to join the war against Japan, following Allied victory over Germany, as far back as the Tehran Conference in 1943.9 The exact details concerning this deal were not finalised, however. Now, at Yalta, they would be and the ‘Agreement Regarding Entry of the Soviet Union into the War Against Japan’ was formalised and signed on 11 February 1945. It gave Stalin all he asked for; in return, the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan ‘two or three months after Germany has surrendered and the war in Europe has terminated’.10

Article 1 stipulated that ‘The status quo in Outer-Mongolia (The Mongolian People’s Republic) shall be preserved.’ This reinforced the existing situation whereby the ‘People’s Republic’ was a Soviet satellite state, and had been since 1924.11 Given that the territory had been Chinese until 1911, this recognition at least provided diplomatic protection against future claims from the former ruler.

The rest of the agreement dealt largely with territory either occupied by, or under the rule of, Japan. In the main it sought to revoke the 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth, brokered by an earlier Roosevelt (Theodore), which formally ended the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War.12 This was explicit: Article 2 began by stating that ‘The former rights of Russia violated by the treacherous attack of Japan in 1904 shall be restored.’13

The ‘right’ that involved the largest territorial transfer related to ‘the southern part of Sakhalin [Karafuto] as well as all the islands adjacent to it’. These were to be ‘returned to the Soviet Union’. Arguably lesser ‘rights’ concerned the ‘commercial port of Dairen [Dalny, Dalniy, Dalian]’ and ‘the lease of Port Arthur [Lushun, Lushunkou]’. These were located on China’s Liaodong (Liaotung) Peninsula, leases to which Russia had extorted with the signing of the ‘Convention for the Lease of the Liaotung Peninsula’ in 1898, and had subsequently lost.14 Article 5 of the Treaty of Portsmouth had transferred and assigned these leases to Japan, and now Stalin wanted them reassigned. There was an olive branch inasmuch as Dairen was to be ‘internationalized’ with the ‘pre-eminent interests of the Soviet Union … being safeguarded’. As for Port Arthur, the lease was to be merely ‘restored’.15

The railways in the area, the Chinese-Eastern Railroad and the South- Manchurian Railroad, were to be ‘jointly operated by the establishment of a joint Soviet-Chinese Company, it being understood that the pre-eminent interests of the Soviet Union shall be safeguarded’. China was, though, to ‘retain full sovereignty in Manchuria’.

The final article, Article 3, of the agreement stated that ‘The Kuril [Kurile] islands shall be handed over to the Soviet Union.’ Though the British and Americans raised no objections to this at the time, it later became hugely controversial. Stalin is recorded as pointing out that, in respect of the agreement, he only wanted to have returned to Russia ‘what the Japanese have taken from my country’, to which Roosevelt replied ‘That seems like a very reasonable suggestion from our ally. They only want to get back that which has been taken from them.’16 The controversy largely arose because the Kurils didn’t fall into that category, their ownership having been settled in the Treaties of Shimoda and Saint Petersburg in 1855 and 1875 respectively.17 The arguments are convoluted, however, and definitely outside the scope of this work.18

The final paragraphs of the document acknowledged that the Chinese government would have to be squared in relation to ‘Outer-Mongolia and the ports and railroads referred to above’ via the ‘concurrence of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’. This seemed to be taken for granted; Roosevelt would ‘take measures in order to obtain this concurrence on advice from Marshal Stalin’. This was no doubt a reflection of reality, given that Chiang’s regime was dependent on American support for its survival. The point was, though, reiterated: ‘the claims of the Soviet Union shall be unquestionably fulfilled after Japan has been defeated’. There was though, perhaps, a sweetener for China: ‘The Soviet Union expresses its readiness to conclude with the national government of China a pact of friendship and alliance between the USSR and China in order to render assistance to China with its armed forces for the purpose of liberating China from the Japanese yoke.’

China, though, was to learn nothing of these matters at the time. Fearing security leaks, Roosevelt kept the agreement from Chiang and his regime.19 Indeed, it was a closely guarded secret overall. Churchill, upon discovering that copies of the document were circulating, fired off a strongly worded memo to his Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden: ‘I am shocked to see that there have been eight copies of this secret document.’ He wanted to know how many copies there were altogether and stated they should not be circulated at all unless ‘in a locked box’. Nobody, including the Dominions, should see it who was not already ‘cognisant of it’.20

The reasoning behind this veil of secrecy was obvious. If the Japanese authorities got word of what was afoot then they would reinforce their already heavily fortified border regions with the Soviet Union. Moreover, they might launch an offensive with a view to blocking or damaging the vital Trans- Siberian Railway. Any such operation could have disastrous effects on the build-up for the planned offensive. Although of much lesser import in the practical sense, there was also a diplomatic problem: the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact of 13 April 1941 was in force. Under the terms of this, both parties undertook ‘to maintain peaceful and friendly relations’ and each agreed to ‘mutually respect the territorial integrity and inviolability’ of the other. The treaty was valid for five years, after which it would automatically renew unless one of the ‘Contracting Parties denounces the Pact one year before the expiration of the term’.21

This ‘scrap of paper’ was, of course, only of utility for so long as both parties found it to be so. It would have no bearing when viewed through the prism of Soviet realpolitik, particularly given that there was only one perspective that mattered: that of Stalin, the ‘unchallengeable individual locus of state authority’.22 Despite being almost affectionately referred to as ‘Uncle Joe’23 by Roosevelt and Churchill, that he was in reality a bloodthirsty tyrant who, according to one of his recent biographers, believed ‘the solution to every human problem was death’ is indisputable.24 That he created a state- sponsored system of mass terror and mass murder in order to perpetuate his rule is equally so. Yet he was no mere thuggish despot. One who observed him at close quarters during the wartime conferences was Britain’s Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Churchill’s primary military adviser.25 Not a man easily impressed, particularly by politicians, Brooke noted in 1942 that ‘Stalin is a realist if ever there was one, facts only count with him, plans, hypotheses, future possibilities mean little to him, but he is ready to face facts even when unpleasant’.26 As is well known, Stalin’s realism was often moral-free cynicism, as in his apocryphal question: ‘how many divisions has the Pope?’ Nevertheless he had other qualities too. As Brooke later recorded:

I rapidly grew to appreciate the fact that he had a military brain of the very highest calibre. Never once in any of his statements did he make any strategic error, nor did he ever fail to appreciate all the implications of a situation with a quick and unerring eye. In this respect he stood out when compared with his two colleagues [Churchill and Roosevelt].27

That Stalin was driven by geopolitical interests and knew what he wanted beforehand, and then got it all, is evident. What he did not do, though, is spring these demands unexpectedly. He had, for example, told Roosevelt’s adviser Harry Hopkins in 1941 that Vladivostok, because of its position, was vulnerable; it ‘could be cut off by Japan at any time’.28 He had reiterated this point to Ambassador Harriman on 14 December 1944, going on to argue that Southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands should be returned to the Soviet Union because of it: ‘The USSR is entitled to protection for its communications to this important port. All outlets to the Pacific Ocean are now held or blocked by the enemy.’29 He also stated that he wished to secure the lease for the ports of Dairen and Port Arthur again, as well as obtain th...