- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Run Me a River

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2021Print ISBN

9780813190709, 9780813122991eBook ISBN

9780813189437RUN ME A RIVER

CHAPTER 1

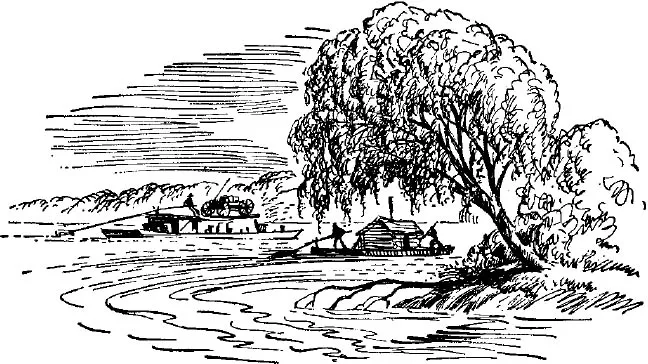

THE river was running full but making no boast of it. It was sliding along under the fog minding its own business as quiet and slick as if the banks had been greased. There came along now and then a patch of foam, sometimes a big patch, sometimes a little patch, looking like pieces of torn tan lace. Once in a while a tree slid down the middle of the current rolling along high and jaunty with a kind of young, wet look of surprise when it bobbled, as if it had committed a gaucherie.

Sometimes a little piece of drift nudged up against the boat and felt of it, rubbed shoulders a minute or two, then having made a long enough acquaintance ducked and passed on by.

There wasn’t a thing on the river worried about the high water except maybe a piece of bank that now and then gave up and slid loose with hardly any commotion at all. Maybe the smallest willow trees were a little troubled for once in a while one of them gave up, too . . . just leaned over and let the river have it, with hardly a sigh for a leavetaking.

The big willow the boat was tied up to wasn’t likely to pay the river any mind. It stood too far back for a cave-in and it was too old and used to the river to do anything more than dip its lowest branches into the water and let them trail out and see for themselves no harm was going to come of it.

Where the boat was tied a little creek ran in. Usually you could cross it on three steppingstones but this morning it was all puffed up with a pride of water. It didn’t have any better manners than to rush at the river and try to push it over to make room. But rushing at all the water in the river was like rushing at a stone wall and the creek got piled back on itself roughly and had to make do with some bank room along the side of the river. It made a fuss around the boat, trying to agitate it a little, but the Rambler was hard to agitate. She rode low and light and it was as if she yawned in the little creek’s face, lifting easy when she pleased and swinging on her line to suit herself.

The two men on the head of the boat were studying the river. This was the Barren, head of navigation on the Evansville-Bowling Green run. Thirty-four miles downstream the Barren flowed into the Green. It was another hundred and fifty miles down the Green to the Ohio and the end of the run, Evansville, Indiana. To steamboat men it was all the same river. You ran on the Green. The big man, named Cartwright, said, “Still bulging in the middle, Foss.”

He was all easy built, with bones that were young and bendable and had sliding, fluid muscles to cover them. Lazy-draped over the capstan he was all curve and bend and the only thickness he had was in his shoulders and upper arms. The forearms were crossed and supported his weight on the capstan and his wrists dangled loose and free. His hands were big and brown and flat and quiet.

He hadn’t ever tried to raise a beard and his face was oily from engine grease and dirty from wood ashes and smoke and the fog damped it and made the places where the brown skin showed through shine. The fog was like frost in his hair, each drop a whole and perfect sphere, as though the hair itself had sweated out the bead. The eyes fixed on the river were blue and at first notice they struck you as oddly out of place with the brown skin. You would expect eyes to match. Then you noticed they were a deep blue, like swimming water, and then they didn’t seem peculiar any more. If you were a woman, and had got used to them, you wished they had been given to you instead. You felt a sort of waste they’d been given to a man, whose only need of eyes was to see with, not be pretty with.

The other man on the head of the boat would have been called big too if he hadn’t been standing beside Bohannon Cartwright. He spirted spit in the water. “Pretty much of a tide,” he said, “but likely it’ll crest soon. Didn’t rise but two inches last night.”

Where the younger man was thick only through the shoulders, Foss was thick all over, chest, belly, thighs, arms, hands, and you’d guess that his legs would be like tree trunks. He was a little lighter skinned than the big man but there was a heaviness of texture as if he had been dipped in a tanning vat and left too long. It gave his face a thick cured look and left it with no expression save that of innocence. You could say he went clean-shaven although since he only shaved on Sundays he carried a graze of stubble on his jowls most of the time.

On the river they said he was baldheaded and that was why he always wore a cap. Bo Cartwright knew better but he agreed with Foss that it might be just as well to keep between themselves what the Lord had furnished him in the way of hair. Foss felt no bitterness about it. “He was running short when he finished me off,” he said.

So, not to shame the Lord, to say nothing of himself, Foss kept his head covered. He tested his beard, now, with a thick thumb and eyed the sheet of water sliding by. Then he repeated himself. “Just riz two inches, Bo.”

Bo cooped a knee around the capstan bar. “ ’Bout dreened off upriver, I’d say.”

Upriver was two hundred miles of bending water and if you knew it from rafting logs and flatboating down it, you knew all the slides and bends and shoals and bars and snags, and you knew Bluff Boom and Greensburg and the Mammoth Cave and Munfordville, and you knew all the creeks and brooks and licks and runs and branches and sloughs, and it was a good thing to know it all; for if you only knew the hundred and eighty miles of river you could steamboat on, you didn’t know what made the river at all.

You didn’t know it headed up under a cliff on a mountainside and ran a trickle down a hollow and then took in other trickles until it could call itself a creek, and then took in other creeks until it could spread itself into a river. There was a place not more than five miles upstream from his home at Cartwright’s Mill where he knew, just by looking at the water, that this was where it happened . . . right there, and almost suddenly, the Green was a full-sized river.

Once when he was a little fellow his father had put him on a horse and had ridden him thirty-five miles upriver to the spring that started it all. Bo had drunk from the spring and then his father had pointed to the trickle and said, “Jump.” When Bo jumped his father had laughed and said, “Now you can say you’ve jumped across Green River.”

It made a difference when you went to steamboating for you never forgot what made the river all the way down.

Foss stumped away to douse the lanterns on the stern, observing cheerfully, “Sun’ll be up soon.”

Bo grunted, which was enough to let Foss know he’d heard.

The fog was sleaving up from the river now, drifting and smoking around the trees and dripping with little slow drops like rain onto the leaves underneath. Bo drew it into his nose with a long breath and it was musty with the dank of wet leaves and sycamore balls and walnut hulls and fish and mud and river water and rotted logs and sweetgum wax. He licked his lips and tasted the fog and all the river smells on his tongue and in his throat and he let the breath out and smelled the smells sharp and acid in the roof of his mouth and at the back of his nose and out his nose.

The patch of sky above the river was reddening and the old gladness in sunup rose in him as it always did. There was never a morning he didn’t feel it, nor ever had been all his life. He didn’t wonder about it. It was for him the best time of day, that was all. He felt the best . . . felt too big for himself. His feet could cover twice the ground and leave it spurned behind. His lungs could burst with his breathing and he felt like shouting and often did, careless of who heard. “Bo!” his father would yell, “quit that bellering!”

In those days, and yet, he felt sorry for a man getting old, who couldn’t any longer jump a rail fence from standing, or walk ten miles every night for a week following the hounds, or climb their one real mountain, old Lo and Behold, without tightening his chest. He felt sorry for it, but sorrier for losing the wish to do such things. That was the real pity—to have time dry up your well of pleasures.

Now, this morning, with as little sleep as he’d had last night and with his load of weariness, the brightening sky lifted his spirits and eased his tiredness. He shoved up away from the capstan and straightened and stood looking and sniffing.

A limb shook above him and rained off its fog. There was a whiffling of wings and a crow flew away, without cawing. Bo watched it thrust across the river and circle and settle in another tree, no different, no better, maybe not even chosen, just suiting the crow as well. From some place far off a rooster crowed. There was a silence and wait, but no answer. The rooster tried again, and waited. Then he tried once more. He sounded fainthearted the third time and not very hopeful and he let his clarion die away only half finished.

Bo grinned. He spraddled his legs and flapped his elbows and stretched his neck and did a thing he had used to do at home. He sent forth a long hoarse challenge which split the air and volleyed and roared and came bouncing back from the cliffs downstream.

When the last echo had died away the cock ashore replied joyously. Bo gave him the proper interval then sent him another blast. He exchanged two more with the cock, then gave him the downdropping sign-off signal that said, we’ve taken care of the sun so let’s get on with the rest of the day.

Foss trod onto the head softly. “Ain’t you ever gonna grow up, Bo? Standin’ there crowin’ at a fool rooster!”

Dropping his elbows but not feeling too much of a fool, Bo laughed. “Wouldn’t no other answer him. He was giving out of hope. You hear how glad he was to find there was one more rooster in the world knew what he had to do when the sun come up?”

“I heard,” Foss said. “You’re both a mite late. I’d say he’s a lazy bird and deserved no better’n he got. Other roosters got their crowin’ over at daybreak.”

“He must of overslept.”

Foss started to speak but a round belch rumbled out and he stopped, surprised. He studied the third button of his shirt profoundly and then, arriving at a conclusion, announced, “That comes of a empty stummick this late in the mornin’. Nothin’ but air in that belly and it’s backin’ up on me. I aim to remedy that right now.” He started off. “You comin’?”

“Right away.”

Bo put his hand on the rope that made the boat fast to the willow and rubbed it up and down some frays. “Wish we had some new lines.”

Foss caught his step on one heel and half turned on it. “New lines is not all we need. We need everything new but a hull. And the only reason we got a new hull is on account the old’n wouldn’t float no more. That machinery . . .” He hauled up and looked directly at Bo.

Bo slapped the line and joined him, his heels clicking as light as a dog’s nails on the decking. “Nothing wrong with that machinery you can’t fix, Foss.” He grinned broadly at the thickset man. “Never was a good steamboat engine ever wore out. You know that.”

“Not a good ’un,” Foss admitted, “but this’n . . .”

“You can sink ’em,” Bo went on, “you can burn ’em, you can leave ’em lay and rust, but they’re not made to quit and you can raise ’em up and clean ’em up and set ’em proper and they’ll chug right along. Now, won’t they? Nothing wrong with that engine except I’m not able to buy new parts like I wish I could.”

Foss remained stubborn. “Ain’t no few new parts gonna change what’s mainly wrong with that machinery, Bo. It’d take enough new parts to make a new engine. She’s just plumb wore out.”

Bo made a rough sound in his throat then leapfrogged over some hogsheads lined in a single row. “Don’t harp at me about no old machinery, Foss. I got me a steamboat. You know how bad I wanted her, and I got her. I had to go to the boneyard to get her and to most she’s not much maybe. But I’m not the most. I’m me, Bohannon Cartwright, and to me she’s fine because she’s mine. Don’t keep on at me about the machinery. I’m just proud we got an engine at all.”

“Well,” Foss hedged, “so’m I, but I got worries, Bo. You can’t git up no . . .”

“What we need to get up we can’t get up? Tell me that. On the Green. Now, tell me. We ain’t aiming to run no races. Ain’t needing a lot of speed. We’re needing just what we got. Something that’ll get up steam and chug along and leave us pick up our freight.”

Foss plodded around the row of hogsheads and Bo watched him with good humor welling up inside him. Foss looked a little like a hogshead himself and it was best he hadn’t tried to handstand over. He never thought whether he liked Foss or not. They had been such a long time together they knew each other as if they lived inside the same skin. You could always depend on Foss. He would always grumble some, for it was his nature;...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Foreword

- Run Me a River

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Run Me a River by Janice Holt Giles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Historical Fiction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.