![]()

Knowledge and Uncertainty

TRAVELING TWELVE time zones has turned my body clock upside down. Before teaching the monks I have one day to adjust to India. First impressions are important, and they start flooding my senses. They begin in Dharamsala, where an Indian community coexists with exiled Tibetans. My son Paul and I navigate the small town in a light rain. On top of our jet lag, we’re enveloped by the heat and humidity that precede the monsoon season. We try to anchor our bodies and minds in this enchanting yet disorienting environment. At some risk to my Western palate I sample Tibetan tea. It’s made with yak butter and salt. The taste is beyond words.

We don’t see many people in Dharamsala, to which we will make occasional visits during our three-week stay at the nearby College for Higher Tibetan Studies. Scattered groups of monks walk between the buildings. A few Tibetan men are in Western dress. We learn they are translators for Western visitors. The Tibetan women wear dark, coarse woolen dresses—even in the summer—that they wrap over a blouse. They sport colorful woven aprons if they’re married. To keep their hands free, they carry backpacks made from cotton or hemp. With heads lowered, they smile shyly as they pass us.

Local Indian kids have taken advantage of a flat courtyard in Dharamsala to set up an impromptu cricket pitch. For all my existential dread—a new land, a challenging encounter of cultures, a deeply emotional time with my son—my native British heart is warmed. I feel strangely at home when I realize that Dharamsala boasts the highest-altitude cricket stadium in the world.

Our final destination is the College for Higher Tibetan Studies. It’s about ten miles down the mountain ridge from Dharamsala, located in rural Himachal Pradesh, a province that extends south to the Kangra Valley floor. The school is a cluster of buildings set into a grove of pine and cedar trees. The cramped site is full of dilapidated buildings. The monks will be living in a campus temple during the three-week Science for Monks program. We’ll congregate in separate common areas for eating, and the monks will join me in an unfurnished room for classes from nine to five, six days a week.

As Western visitors, and part of the teaching staff, we’ll live in a plain three-story building made of cement and concrete blocks. Down the hall from us is our American host, Bryce Johnson, an environmental engineering PhD out of Berkeley. At age thirty-three Bryce quit a promising postdoctoral position to become organizer of the Science for Monks program. His commitment will sustain us through thick and thin.

Paul and I unpack in our small room. It has a linoleum floor, two cots, and a narrow table. The windows have canvas curtains and ill-fitting screens. We bypass the small wardrobe, deciding it will be easier to live out of our suitcases. The bathroom is bare tile with a shower head coming out of the wall on one side, a small sink, and a toilet with a cracked seat. Toilet paper is thin, unbleached, and pale gray. There’s a bucket on the floor for washing clothes.

Outside, the campus is sleepy in summer, with few people beyond those associated with our program. Dogs lie in the shade of most buildings. The school’s classrooms and offices fill one of those concrete buildings, and I’ll be teaching in a classroom on the second floor, in a space no more than five meters on a side. But the plainness that characterizes the Tibetan enclave also reveals hidden splendors, as Paul and I have already discovered.

Back in Dharamsala we tour the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. We leave our shoes at the entrance, and red curtains are drawn so we can enter a room suffused with soft, warm light. The room is filled with floor-to-ceiling cabinets. Behind their glass doors are hundreds of scrolls tied with ribbons and encased in wooden planks wrapped in colorful fabric. Some are in Tibetan and others are in Sanskrit. They’re the painstaking work of monks over the centuries.

In time I will also see the Tibetan art of making sand mandalas. These symmetrical designs, created on a flat surface with colored sand, are an expression of the Kalachakra, the Tibetan wheel of life. They’re exquisitely colored and perfectly formed patterns of sand grains. The monks create them with a small brass funnel that pours sand through a narrow opening. They tap gently on the side to ensure smooth flow, “drawing” on the surface with lines a dozen grains wide. One mandala takes four or five skilled practitioners several days to make. Then, to my amazement, they’re swept away in seconds as a powerful reminder of the impermanence of reality.

It takes time for me to understand why such an exquisite undertaking ends intentionally in destruction. In my Western tradition, progress and success are expected. Scientists want to learn new things and build an edifice of knowledge, and we intimately tie our careers and institutions to that quest. All of this seems irreconcilable with the Buddhist precept of evanescence, as illustrated by the sand mandala. Buddhists believe we live in a cosmos with endless cycles of time and existence. Human concerns are insubstantial and impermanent, so the best way to live, according to the Buddha, is to avoid all attachments. Is this Buddhist idea going to have any appeal for me?

At moments like this, I’m reminded of a Western analogy. A century before the Buddha, the Greek poet Archilochus said, “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” That, of course, is how to escape the wily fox, making the hedgehog the final victor. Over time I’ll come to see that Buddhism has “one big thing” that has allowed it to endure, even prosper, under difficult circumstances, and it is exactly this idea of impermanence and nonattachment. Buddhism sees us as merely temporary vessels of thoughts and emotions, so freedom from worldly attachments is the goal of life. This outlook has an obvious wisdom, and even a psychological payoff. What appeals to me especially is that Buddhism delivers its wisdom without theology or gods. From what I understand, it’s also very pragmatic, like science.

On arriving here, I’ve also recognized that Western science has one big thing: its critical, experimental, and logical method. This may be a kind of attachment, but it seems necessary to overcome our ignorance. I’m waiting to see how this comes across to my new friends, the Buddhist monks. If I have a somewhat romantic view of Buddhism, the same goes for how the monks seem to view science. As I’ll soon learn, most of them are new to science. They idealize it as a way to measure everything with perfect accuracy. Science in their eyes is authoritative but also aloof. I hope to teach them that science has a wisdom tradition, too. Like the making of scrolls and mandalas, it can embrace art, play, and mystery.

Our first day has been exhausting. My mental aspirations struggle against an incredible fatigue. Paul and I flop onto our narrow cots. I feel ragged but must try to get some sleep. Tomorrow morning class begins.

HITTING THE MARK

Through the drizzle of the coming monsoon, the Sun rises across the campus. It catches mountain peaks and corners of trees and taller buildings. It scatters off the water drops to fill the air with a warm glow. I’ve arrived at the second-floor classroom to find three dozen monks—at first almost indistinguishable with their bronze complexions, black hair, and maroon robes—ready to learn about science. From the sea of faces, they will emerge as individuals with distinct personalities, and some of them will teach me lessons I couldn’t learn anywhere else.

One of these monks is Thupten Tsering. He will become an ally in my efforts to make the science instruction interactive and interesting. I will often call him “Thupten B” during my time in India since Tibetan names are limited in number; there’s another Thupten Tsering in the class. You’ll get to know Thupten by his appearance: age twenty-nine, he’s sturdy like an ox, compact and muscular, with a soft, round face and sleepy eyes. He’s also prone to giving bear hugs and lifting others off the ground.

Thupten is from a large monastery in the south, and like many in the region he shows the mild facial scars of tuberculosis. He overcame the disease but it cut short his studies by a year. Now he’s two years away from his geshe exam. While not as senior as some monks in the group, he radiates a quiet authority. For me he’s a godsend: his English is perfectly articulated, his note-taking superb. He’ll be able to help other monks to write journals on what they’ve learned and add reflections. I can’t go wrong with Thupten B. He carries in his bag a hefty and popular Western book on cosmology, Simon Singh’s Big Bang, but even better, he effortlessly conspires with me to teach the other monks.

For the first day of instruction I begin with something lighthearted, even comical. Thupten helps me orchestrate our first lesson: how scientists deal with uncertainty.

Picture a classroom with a whiteboard, a few windows, and thin pads for sitting. We’re all standing, and after we clear an area, I bring Thupten forward, blindfold him, and give him a red marker. He knows what’s coming so I spin him around five times. When he stops, he staggers a bit, playing a drunk. It’s amusing since Buddhists are teetotalers. I aim him toward the whiteboard. On the board is a black dot at eye level. Thupten walks forward to try to hit the dot. A natural-born actor, he lurches around and careens into the monks standing near a side wall. He stabs the marker at them, but they dodge and duck. He finally hits the wall, but very wide of the mark. More blindfolded monks will try this feat, minus the spinning. But the point is the same: we’re coming to grips with uncertainty. Science calls this random error.

The monks take their turns, moving ahead tentatively or with vigor. Some of their marks are close to the target black dot, others are several feet off. Those who miss by a lot receive friendly guffaws. But I tell the monks that this is exactly the way that science—often blindfolded when it comes to measurements of the universe—arrives at as precise an estimate as possible. For example, the monks’ overall result shows very little dispersion of the red marks vertically. With fairly good accuracy, they get near the black dot by lining up their hands before moving forward. However, their red marks scatter broadly in the horizontal plane, which they had no fixed way to judge.

I approach the whiteboard and draw a squat oval that includes two-thirds of the marks; this is a classic error “ellipse.” Whether wide of the mark or on target, there are no “good” monks and “bad” monks. All the hits are part of a normal error distribution. I imagine the ghost of Carl Friedrich Gauss watching in pleasure; the German wunderkind developed the theory of random errors when he was just a teenager.

Now we do a second version of the experiment. Without being blindfolded, the monks aim magnetic darts at a metal sheet attached to the whiteboard. Everyone has a few practice throws before the one that counts. Some monks come close to hitting the black dot that’s the target. Others spray darts across the metal sheet, and a few miss it altogether. The monks quickly realize that they can align themselves horizontally with the black dot but can’t help shooting well above or below the target. They have trouble judging the arcing trajectory caused by gravity. I draw an ellipse around the majority of the hit locations, and this time it’s elongated vertically. Compared to the blindfolded experiment, the second experiment produces an ellipse that’s smaller. Being able to see the target helps the accuracy, but it still produces random error.

When astronomers face the vast universe, I tell the monks, they do something like what we’ve pulled off in the classroom. Astronomers point their markers and throw their darts, so to speak, and like the monks, they live with the random error associated with any measurement.

During our first day in class we’ve broken a lot of ice. Our classroom breaks are dedicated to tea time, Tibetan or Western. As the monks walk past me, they flash smiles, a welcoming experience indeed. Their fraternity is obvious. Some walk with arms around each other’s shoulders. They’re unafraid of physical contact and genuinely seem to like each other. After just one day, the experience of teaching these gentle men is starting to change me. For my break, I go for a brisk walk and begin to take stock.

I’m struck by how completely the monks throw themselves into these experiments. In Arizona I teach hundreds of freshmen, and they arrive at the university with a limited knowledge of science. By contrast, however, they’re exceedingly sophisticated in their awareness of social status and the opinion of their peers. To volunteer in class, for example, is generally uncool. The enthusiastic students are in a minority and swimming upstream. Clearly, this isn’t the case with the monks. In Arizona, it’s hard to find students willing to risk their dignity in a demonstration or experiment. In my humble classroom by the Himalayas, they volunteer with vigor. I’m reminded of the unbridled enthusiasm of fourth-graders back home.

I try not to be too cynical about Western education because it’s still the best in the world and I love my job. And yet . . . teachers mostly stay behind a “fourth wall” and try to maintain order and structure. Students mostly accept the peer pressure that favors passivity. In the old Soviet Union, the trope was “They pretend to pay us and we pretend to work.” The equivalent in too many American classrooms is “The teacher pretends to teach us, and we pretend to learn.” Information is dispersed, memorized, and regurgitated in exams. We hope that it sticks or, even better, that students are “learning how to learn.” But the awkward truth is that creativity in the classroom—from either teachers or students—is disruptive and tends to be discouraged.

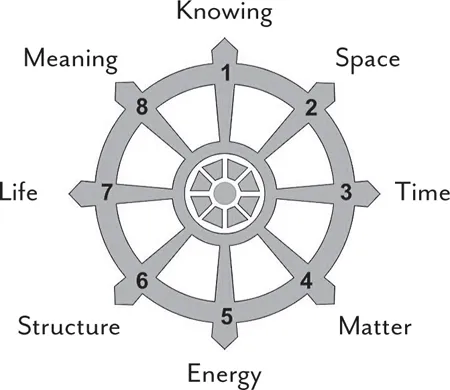

Figure 1.1. The subject matter of the course overlaid on a Buddhist dharma wheel, an allusion to the eightfold path to enlightenment and the eightfold way that led to the quark model of subatomic structure.

The brisk walk is pumping oxygen to my brain, but I don’t think my impressions are just euphoria. After one session in this drab classroom in the foothills of the Himalayas, I’ve had a new kind of teaching experience. I was ready for resistance, but the door was already open. These monks seem happy to accept the fact of human ignorance. If you’re not attached to knowledge, learning is simply a gift. They will risk embarrassment to learn. My need to control the class isn’t as pressing as usual. The monks are cocreating our lessons. One educational aphorism says, “Learning occurs at the boundary between structure and chaos.” I think I’m watching it happen. Before I left Arizona, I was so uncertain about how to present the material that I jettisoned my previous notes and lectures. I started from scratch, a scary move at first, but one that’s proving liberating.

By the time I return, the monks are filing back into the classroom. They sit cross-legged on their mats, and we continue our discussion of error and uncertainty. My translator today, and for most of the days to come, is Tenzin Sonam. Tenzin has a degree in engineering and is on staff at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. He’s not a monk. You’ll know him, too, by his appearance. In his late twenties, he wears T-shirts and chinos, and he has the high forehead of a thinker and the milky coffee complexion of a Tibetan. He’s a superb translator between English and Tibetan, a process that still amazes me.

I tell Tenzin we’re going to cement our earlier lesson. Each monk receives a wooden ruler in millimeters and I ask them to measure the width of the whiteboard. It’s about eight meters across, so they have to place the rulers carefully end to end twenty-five times. As they finish I collect the answers and make a histogram, which is a kind of chart of results, ideally looking like a bell curve in the end. Our result is slightly ragged but it’s also pleasingly symmetric, with a mean of about 785 centimeters and a scatter of about four centimeters.

“Who got the answer right?” I ask.

Half the monks put their hands up, and the other half guffaw and hoot with mock derision. I notice they like to joke with each other about such conceits as, “Who got the right answer?” “Who throws best?” and by implication, “Who is the best monk?” So I play on this, because it’s a good lesson in science as well. With random error there’s no single “best” result, only averaging of intrinsically uncertain measurements.

“Who’s t...