- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

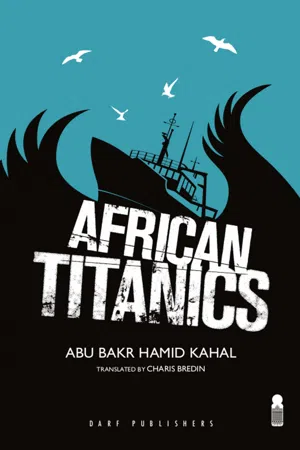

African Titanics

About this book

African Titanics is the untold tale of the African boat people and their desperate exodus to the merciless shores of the Mediterranean. The novel is one of fleeting yet profound friendships, perseverance born of despair and the power of stories to overcome the difficulties of the present. Alternating between fast-paced action and meditative reflection, the novel follows the adventures of Eritrean migrant Abdar. As he journeys north, the narrative mirrors the rhythm of his travels and the tension between life and death, hope and despair.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Migration came flooding through Africa, a turbulent swell sweeping everything along in its wake. None of us knew when or how it would end. We simply watched, dumbfounded, as the frenzy unfolded. From all across the continent came mournful lamentations: ‘Africa will soon be no more than a hollow pipe where the wind plays melodies of loss.’

I, and many others beside me, attributed it all to the work of a dark sorcerer emerging from the mists of the unknown and sounding a magnificent bell, whose resounding tolls had stirred Africa’s youth from their long slumber. The depths of the bush began to tremble and shake, and wherever the sound of the bell reached, life would never be the same again. It was a pandemic. A plague. And not a single young soul was left untouched. Dong, dong, dong, pealed the bell, calling one and all to its promised paradise.

On and on it went, infecting our minds with the migration bug. For quite some time – perhaps five years – I managed wilfully to ignore it, relegating it to the ranks of all the other meaningless noises of my daily existence: the thunder of dynamite blasted through Eritrea’s mountains by the Italian workers from De Ponti and the milkman’s cries as he drove his donkey through the dingy alleyways. But after all those years it turned out that the bug had got me anyway and, one day, I woke up wondering how I could have ignored it for so long. From that moment, I was obsessed, tirelessly pursuing the chiming bell wherever it called me. I was plucked from Eritrea, swept across the Sudanese border and on into Libya, in the dark of night. I was lost, and almost perished in the desert, before slipping through into Tunisia. I remember feeling as though I was fated forever to continue my ceaseless roaming, and that I would never again escape the endless road.

Later I thought of the years before my departure as sheltered years, or perhaps confined years, when I was still immune to the bug, clinging earnestly to my convictions. In my youthful naïvety I even penned a play, entitled The Phantom and the Mask. The piece was staged in my town theatre, and I still have a rough copy of it for any who require further proof of my authorship! My play warns of the dangerous ideas that prey on all people alike, regardless of their class or social group. Its premise was simple: a masked demon enters a local village, his voice metallic and the smell of human flesh clinging to his frayed cap and leather shoes as he pushes a cart of dead bodies before him (the cap and shoes are, it turns out, made from human skins). The demon casts a hypnotic spell over the villagers and they are transformed into hideous beasts, submitting mindlessly to his every command. Admittedly, the premise was naïve, crude even – yet it was precisely what guaranteed my protection for so long.

All around me, I sensed the dangerous lure of migration: a photo of a young friend leaning against a gleaming car in a European city, acting as though he owned it when, in reality, he had amounted to no more than a dog-walker; a lucky soul returning from abroad in record time – and in a flashy car – with a beautiful lady on his arm; an epic letter from a man long absent, promising to return and settle for good in his beloved homeland for, in his words, he has amassed enough wealth to start up a bank. The truth of the matter was that he would probably never return, and was shamefully lying about his outrageous wealth. As for those who returned with university degrees, most of whom were penniless, no one paid them any attention. They aroused universal scorn for returning without pretty women or cars.

After much reading and researching, I also discovered the startling similarity between that seductive bell, luring us away from our quiet lives (which still counted as lives, after all) and another bell, owned by a wicked wizard who’d lived in Europe long ago. One day, the story goes, this wizard entered the gates of a European city and began to prowl through its streets, rhythmically striking his bell. At first he seemed harmless, but the ensuing events turned the tale into a tragedy. With the chimes of his bell, the magician enchanted the city’s children. No sooner did they hear it ringing than they submitted with heart and soul, trailing after it in a daze to the forest outside the city, overcome by their longing to be united with it. Even those who froze instantly on the spot, overcome with euphoria, were not spared by the chiming of the bell. The children’s mothers were filled with dread as they watched their children taken from them. But they refused to give up. They fought heroically to save their little ones, and their deeds have been recorded in the annals of history.

Unlike the children, we had no one to shield us from our sorcerer – or at least that was what I thought. But one day I relayed my musings to Malouk, a Liberian whose fate was deeply entangled with my own for quite some time, and whose departure left a deep well of sadness within me that still torments me to this day. ‘I know an African story just like that!’ he beamed. ‘Only difference is that mine is real. It happened not long ago and its heroes are still alive and well.’ He then presented me with a manuscript which he had begun in order to practise his handwriting, filling its pages with sundry anecdotes. He directed me to the story of Loulou Kajamkour – nicknamed Kaji – and his brave struggle to protect his nephew Bouwara from the migration bug.

‘Read this one,’ he instructed me, ‘I just hope my terrible writing doesn’t put you off.’

Malouk had entitled the pages The Adventures of Kaji. They were a harmless jumble of events, he wrote, passed on by those who were afflicted, like him, with a compulsive need to hunt out strange events and paste them together into an ancient, miscellaneous map which they would spread out at late-night gatherings. I began to read:

No sooner had the first ships reached the far shore with their small load of passengers than tales of them spread along the African coast and across the whole continent, travelling with the usual speed of all strange and wonderful stories. Reports of the unlucky ships that had sunk were naturally less welcome, swiftly and wilfully forgotten in favour of happier events and gossip. Friends and relatives of those lost on the boats would continue to watch the reports hopefully for some time, but any chance of learning their fate was soon abandoned. The feverish debate went on and on.

‘The reports are true, no doubt about it … ’ Bouwara, seated in a noisy tavern, insisted to his uncle.

‘Nonsense. Forget about those half-baked stories,’ Kaji interrupted him.

‘Half-baked? Who are you to say they’re half-baked? Listen here, Loulou Kajamkour, maybe it’s time you took some advice for once – but I don’t want to end up in another endless argument with you.’

Kaji had reluctantly agreed to meet his nephew in a remote tavern. In spite of the age difference between them, they had spent their evenings together for many years, on the condition that Bouwara would give liquor a wide berth and content himself with fruit juice and dancing.

Now and then, Kaji raised his eyes to the roof, a jumble of criss-crossing wooden planks. He felt a strong urge to take up the matter of this so-called roof with the tavern owner as he watched the moon through its gaps; a small, lonely sphere in the furthest reaches of the sky, surrounded by pale, scattered stars. He made no move, however. ‘Why must I speak of such stupid matters?’ he wondered to himself, ‘I didn’t want to come here in the first place. I didn’t want to talk about this roof.’

‘Listen here, Kaji,’ Bouwara was still holding forth, pressing his uncle to concede something. ‘At least just tell me you believe the ships arrived in Lampedusa?’

But Kaji was on another planet. Despite grumbling about the location of the strange tavern and its rowdy customers, he decided that there must be something or other that attracted them to it. Perhaps it was that intensely deep moon surrounded by twinkling stars. He took a draught of his drink and felt it burn in his mouth, instantly wanting something to eat. And anyone who knew Kaji would not be surprised he was suffering such pangs of hunger at that time of day. He had, over the last few years, made a habit of having only one meal a day so that his many children could eat. It was now the hour when his insides were used to receiving a scrap of food, but instead Kaji continued to drink on an empty stomach.

Whenever Kaji drank, however, his tongue would loosen into sweet song, a habit of which Bouwara was greatly fond. Among the songs that he performed that merry evening was a stirring tune called ‘Joy’ which tells of the delight and astonishment of the first man on Earth when he sees woman for the first time. The song must be performed with laughing eyes, smiling lips and the tone of one telling a story. It is accompanied by rhythmic beats and the stamping of feet to mark the movement from one section of the tale to the next, and a deeply soulful air encompasses it.

Kaji had resolved not to let Bouwara leave, to cure him of the migration bug with the songs he performed so well. He vowed to himself that he would not give up until Bouwara was finally free to live his life as a farmer and as an inheritor of songs, for this was his destiny.

As I said, the song came to the lips of the first man on earth. After many years of solitary existence, this man began to feel that something was missing from his life: there was a terrible and intangible void he could neither fill nor define. Whenever he got close to pinpointing what it was that was missing, the notion of it would slip through his fingers again.

During one of his many periods of meditation, as he searched for the nature of this absence that allowed him no peace or contentment, he let his imagination run wild. And then, with sharp stones, he began to carve up a tree trunk, allowing his hands to follow the patterns of his dreams. After finishing this artistic endeavour – the very first fruit of man’s labour – he carried his woman-shaped statue to bed and lay down next to it. On waking, he found her next to him, awake and smiling the sweetest of smiles.

This is when the ‘Song of Joy’ began, out of a soft cry of surprise, an awkward gesture, astonishment, out of life itself and the perfection rendered by the imagination of our ancestor, the

artist from whom we all are descended. It came from the unexpected vision of a beautiful, gentle-hearted creature.

Folklorists categorise this song – which is closer to a prayer – as Africa’s earliest musical and narrative heritage. Some even claim the song as a prophecy, a ‘Unique Cry,’ the likes of which will never again be heard throughout humanity’s long history.

Malouk’s tale left me reeling, captivated by this first glimpse of the rich world of his imagination – a world that was to become so very important to me – as well as deeply moved by the idea that the power of song can overcome sorcery.

Chapter 2

I was completely worn out after racing to and fro between Khartoum and Omdurman for days on end, tirelessly tracking down the ever elusive smugglers. I would cross into Khartoum from Omdurman along Cooper Bridge – an iron relic from the days of the British – and return via the wide Shambat Bridge. Trundling over Cooper Bridge I always felt terrified that our bus would topple into the Nile, dragging us all down with it. I was convinced the other passengers felt the same, although they tried to hide it. My clothes would be soaked with sweat, dry out and then be dripping wet all over again, as I came and went throughout the day. Meanwhile, the wound on the arch of my foot was excruciating – I hadn’t bothered to treat it and the area around it had become painfully swollen. Whenever I trod on a sharp object a searing pain would engulf me, and I’d end up limping around for the rest of the day. As a result my friends had wittily taken to calling me ‘Limpsalot.’ They seemed to have nothing better to do with their time while we waited to cross the Sahara than vying with each other to come up with the most apt nickname for me.

During our stay in Omdurman, I often returned to our rented lodgings in al-Arba‘in at around midnight. Those who were still awake would gather round to hear the latest news from the smuggling world. Usually I humoured them, but one night I decided to tell them nothing and instead tossed them a newspaper, telling them it contained an amusing story – that way I could hopefully distract them from teasing me and hassling me for news.

The newspaper did indeed contain a very strange report about a zookeeper who’d been dismissed from Khartoum Zoo. He was suspected of abusing his position in the worst possible fashion, and a committee had been hastily assembled to investigate the various accusations against him. The jubilant headline read: ‘The man who ate the lion’s lunch.’ In short, a zoo employee, whose job was to feed the park’s sole lion, had for many months been filching bits of the poor beast’s dinner. He had only given the lion a mere three of his apportioned seven kilos of meat. The lion had grown visibly gaunt, while the thief was now unreasonably plump. This curious story prompted outbursts of laughter in our house that night, and we decided to visit the zoo the following day to pay our respects to the poor swindled lion.

After wandering around the zoo for some time, we eventually found the lion crouched in a corner of his cage. We’d brought a fresh chicken from the butcher as an offering, but when we pulled it out of the bag ready to chuck into the cage, a man suddenly appeared in front of us and snatched it from our hands.

‘I’m in charge around here,’ he introduced himself. ‘He won’t eat anything strangers give him. I’ll throw it to him at dinner. It’s very unusual for visitors to bring food for the animals, you know.’

‘We read about the man who ate the lion’s lunch,’ I replied.

The man immediately burst out laughing. ‘I heard about that,’ he said between guffaws. ‘Do you people honestly still believe what you read in the papers?’

‘Are you saying it’s not true?’

He laughed even harder, and said nothing more, so we left him the chicken and hurried away from the zoo.

‘Maybe our friend back there is the one who ate the lion’s lunch,’ one of my companions suggested as we passed through the main gates...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title

- Acknowledgement

- Dedication

- Contents

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access African Titanics by Abu Bakr Khaal, Charis Bredin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.