I LIKE IT WHEN I can be done with something. Like a knitted earwarmer, like winter, spring, summer, fall. Even like Epsilon’s career. I like to get things over with. But impatience has consequences. That time when Epsilon gave me an orchid for my birthday. I didn’t really want an orchid. I never got the point of flowers, they’re just going to wither and die. What I actually wanted was for Epsilon to retire.

“But I need a refuge, away from all the . . .”—for a second I thought he was going to say “togetherness,” but instead he said “nakedness.” “Does that mean me?” I asked. “I’m not naming any names,” he said.

So I undressed for the orchid instead, and soon the buds began to blossom, little pink flowers were springing out everywhere. “I wish you had the same effect on me,” Epsilon said.

The directions that came with the orchid said to prune the flowers after they wilt, then they’d revive in six months. First, though, the flowers had to die. So I watched and waited and finally I couldn’t stand it any longer. Time to be done, I told myself, and then I pruned the plant down to its skinny, bare stalks.

“What happened here?” Epsilon asked when he came home from work. “I did what I had to do,” I said. “The flowers wouldn’t wither. But don’t worry. There will be flowers again in six months, just in time for fall. If I’d waited any longer, we would have risked not having flowers until winter.”

But fall came and went, and then winter, and then spring, the flowers didn’t return, the orchid was dead, and for my next birthday I got a throw pillow.

Now that I’m lying in bed, I’m the very opposite of impatient. I’m wishing I could save what little I have left of my life until I know exactly what to do with it. For that to happen I’d have to lock myself in a freezer, but all we’ve got is the small one in the refrigerator. I can hear people coming home from work, they’re thinking about their dinners, and here I am in bed, and the whole thing reminds me of a book I once read.

Maybe I should turn off the lights. Not that it matters, the man with the scythe can see in the dark, he’ll find me no matter what. What will it be? My legs? My arms? I’m wondering. I wiggle my fingers and toes. The left side of my body’s numb. The right side too. It’ll probably be my heart. Before Epsilon, my heart was like a grape, and now it’s like a raisin. Or maybe my shriveled tonsils? You can’t trust those things.

It may take a long time before anyone realizes I’ve died. I read about a Chinese man who was dead in his apartment for twenty years, they could tell from the date on the newspaper on the kitchen table, and when they found him he was just a skeleton in pajamas. I’ll wind up a skeleton in pajamas too. But, I’ll start to smell before that, and first the neighbors will think it’s the Pakistanis on the first floor, but when the Pakistanis start complaining too, someone will remember the little old lady on the third floor. “But didn’t she get shot dead during the war?” they’ll ask. “No,” June, my next-door neighbor, will tell them. “I saw her last Christmas. Time to call emergency.”

When I was a child, I always dreamed of being taken away by an ambulance, and when there was one nearby, I’d cross my fingers and whisper: “Let it be me, let it be me,” but it never was me, the ambulances were always moving away from me, I could tell by the sirens. Now I hear ambulance sirens in the distance again, they should be coming to get me because I’m wearing clean underwear and will be dying soon. But no, there’s someone else in the ambulance instead, someone who’s no longer responsible for their own destiny.

It’s getting dark, I’m trying to concentrate on something useful, and the only thing that matters now is to figure out what my last words will be. “The probability that we’re going to die is smaller than ε, if ε equals a microscopically small quantity,” I told Epsilon. It wasn’t like me to say something like that. I wish I’d said something different.

I want to say something meaningful, make my last words rhyme, so I lay awake the whole night trying to think up something appropriate. I know I’ll never get out of bed again. But then morning comes and I feel so hungry.

Epsilon says that, statistically speaking, a given person will probably die in bed.

Maybe I should get up now.

LIVE LIFE. Seize the day. I’m standing next to my bed, but I don’t know how to seize my day. Finally, I decide to do what I always do: read the obituaries.

But first I head for the bathroom. I’m still wearing the black dress from the day before, and from many days before that. Yesterday my dress was especially black. Epsilon is a short man, so I don’t know why the bathroom mirror is hung so high. Epsilon says he’s happy with it because he just needs to see where to part his hair. My back’s so bent I can’t see anything. I stretch myself and then putter up to the counter on the tips of my toes. Now I can see the upper half of my face in the mirror, like a nixie lurking with half its head sticking out of water, to lure you in. It’s strange to think the half-face in the mirror is me. I look straight into my eyes. Why bother with appearances when no one’s looking? I go out into the hall to get the newspaper.

It’s possible that my next-door neighbors, June and his mother, know I exist. Even if they do, they won’t miss me when I’m gone. They’re the only ones besides Epsilon and me who’ve lived here since the building was first put up, and I remember June from when he was a little boy. His real name is Rune, but his mother can’t pronounce the letter r. It was probably his father who came up with the name because he had a special interest in old languages. Later, he got interested in accountants. June’s mother is one of the few people I’ve ever been in the habit of greeting regularly. This was back when we first moved in and I didn’t know any better. “Hello,” I’d say every time we passed in the hall. And since we passed each other several times a day, the routine got awkward pretty quickly. In the morning it was fine, but then we might see each other when she was coming up from the cellar and I was appearing out of the blue. “Hello.” A couple of hours would go by and then we might run into each other outside the laundry room. Each time, I’d say “how are you?” and force myself to smile. When I took garbage to the chute at night and she was hovering around on some mysterious errand, I’d pretend I had bad night vision and couldn’t see her. I’d feel my way along the wall in the dimly lit hallway, and the next morning the whole painful routine would start again. It was a relief when her husband left her for the accountant on the floor below and she stopped going out. June was still a kid, and suddenly he was forced to run all the household errands himself, so maybe it isn’t surprising that he grew into an unlikable adult. He never said hello when he saw Epsilon and me, and I didn’t say hello either. So after the deaf woman moved out of the apartment building, I left all other greetings to Epsilon. “Morning,” Epsilon would say and June would ignore him, except the one time he gave us the finger. “How fun,” Epsilon said. He wasn’t trying to be ironic, Epsilon is never ironic. “That’s a new one. Probably something he picked up in the Boy Scouts.”

Sometimes June or his mother peeks out their door at the very moment I do, to grab their newspaper off the mat, and it’s uncomfortable every time.

I sit down at the kitchen table with my toast. I open the newspaper at random pages until I’m surprised by what I’m looking for. Whenever I buy a bun at the bakery, I always eat the custard in the middle first, and I approach a newspaper in the same way. The list of bankruptcies are like the coconut and the obituaries are the creamy filling. Today I’m glad my name isn’t there. Still, an obituary would be proof of my existence, and I wonder if I should send in my own obituary and tell the newspaper to hold on to it and print it when the time is right. I used to read the obituaries to gloat over all the people I’d outlived, but now I don’t think it matters, we all live for just a moment anyway.

We’ll keep you in our secret hearts, and hold you there so tight, You’ll dwell in loving memory, a dearly cherished light.

Wouldn’t it be nice if someone remembered how pretty and smart and funny I was, maybe if I’d had children they would’ve inherited my talents, whatever those are, and my wisdom could’ve been passed on to the next generation: “Remember to exhale gently in order to puff out your lips when you’re being photographed, my dear daughter.” But nature only cares about preserving and perpetuating the species, it couldn’t care less about individuals, and the fact is that nature actually prefers for individuals to live as briefly as possible, so that new generations can take over faster and evolution can speed up, which is an advantage in the struggle for existence.

“The laws of nature are in direct conflict with our individual interests,” Epsilon said. “Isn’t that what I’ve always told you?” I asked him. Ever since Stein died, Epsilon had his nose buried in a book. “What are you reading?” I asked. “I’m reading what Schopenhauer has to say about death,” Epsilon said. “I’m trying to make peace with the fact that Stein’s gone.” “But you’re religious,” I said. “No, I’m not,” Epsilon said. “Oh. So you’re hoping to find some other, enduring meaning for Stein?” I asked. Epsilon nodded. “Something like that.” “Does Schopenhauer have anything useful to say?” I asked. “Well, the part where he says that Stein will continue on as an expression of the world’s will seems a bit much,” Epsilon said, “but the thought that he’ll live on in the species of Dog, there may be something to that.” “So if I imagine a dog in a garden a thousand years ago, standing there eating grass as though this is the solution to all its problems, and then a dog standing there eating grass today, it would in a way be the same dog? That’s not as comforting as you might think. Stein was Stein, after all.” “Schopenhauer claims you have to overcome the idea of Stein as an individual,” Epsilon said, “you have to start identifying him with the totality, because as a part of the totality he’ll live on as Dog for a very long time.”

Perhaps I should stop seeing myself as an individual and start identifying myself with the totality, but I just can’t do that, I’m about as far away from the totality as you can get. But maybe it’s not too late. I let myself imagine that someone might notice me on the way to the store. But what would I do if that happened, probably nothing, and whoever it is might be disappointed by what they see. I’ve never heard of anyone being impressed by nothing, after all, and I don’t like to disappoint people.

I have to look through the peephole for a long time before I go out. But I’m not complaining. It’s worse for those who have monocles because their vision is going. I wait until all the neighbors on my floor and the floors above have gone out, and the outer door on the first floor has closed a few times, and then I can go out too. I don’t shop on the weekends, when too many people are out and about, and Epsilon is at home. I creep down the stairway, then hurry past the neighbors’ doors and mailboxes. One time my name was on a mail-order catalogue and I almost bought “the hilarious, one-of-a-kind plastic moose head that sings when you move, guaranteed to make you laugh for years and years to come.” But Epsilon prevented it.

When I step outside, I force myself to look up. Nice sun, I think, before looking down at the trash blowing around in the gutter. It’s been a month since the superintendent’s obituary appeared in the newspaper.

“He died an unnatural death,” I said. “Sorry to hear that,” Epsilon said, but he seemed more upset that that stubborn zipper on his jacket was stuck. “He should still be glad that he reached the average life span,” I said.

But now I’m not so sure. I’m not sure of anything anymore. The courtyard of our building is a mess, and even though I’ve seen a lot of things in my time, I’m still surprised to find a half-eaten cupcake in a hedge.

There are two young mothers with baby carriages sitting on the grass in front of the building, and even though I’m staring at the asphalt less than usual today, they don’t notice me, which is probably just as well, since I saw on TV that people don’t say “hello” anymore, but instead ask “what’s up?” and I just wouldn’t feel comfortable with that.

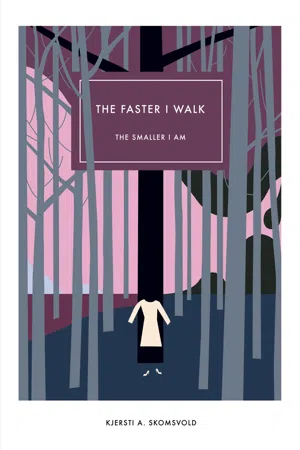

I follow the sidewalk past the large strip of grass between the buildings and then turn onto the gravel path leading between a line of trees, where the Østmarka forest ends, and then there’s just fifty meters or so until I come out on the other side. After that, I walk along the hill past the church, which looks more like a swimming hall, and head for the grocery store. I’m walking pretty fast, but I don’t sweat anymore these days.

There’s a senior center over the bridge behind the grocery store, but I pretend it’s a motorcycle club or a dance hall or something I wouldn’t care about anyway. I took dance lessons when I was twelve. Everyone wanted to dance with the lovely Ellisiv, the other kids lined up and took turns. And sometimes, when they least expected it, she’d tip her wheelchair back a little to startle them. I always danced alone. For half an hour I’d be the girl and for the other half hour I’d be the boy.

It’s cooler inside the grocery store than it is outside. They’ve only just opened. Actually, I prefer it when there are other customers in here, so I don’t attract attention. I usually buy what other people buy, it’s nice to have boiled cod for dinner if the woman in front of me at the checkout is also having boiled cod. “We’re not the only ones eating cod today,” I say to Epsilon, knowing he appreciates this.

I pick a few apples from the fruit display. Ever since Chernobyl, I always peel Epsilon’s apples so his brain won’t be affected by any trace of radioactivity. My own apples I just buff on my skirt. I find the cheese, Epsilon likes brown gjetost. I prefer strawberry jam, but jam jars are impossible to open. And when it comes to jars, Epsilon is no help at all. I also like pickles. Then I realize that I could ask an employee to open the jar for me, and I could just screw the lid back on lightly for the trip home, and so I find the jam aisle. There they are: jar upon jar, stretching from floor to ceiling, and even when I put my hands on my hips and lean back, I can’t see to the top of the shelf. They all look like they have a screw lid, though, so I just pick one at random.

I’m frustrated because both of the store’s employees are standing at their checkout counters, and I’m the only customer in the store. I don’t want either of them t...