- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

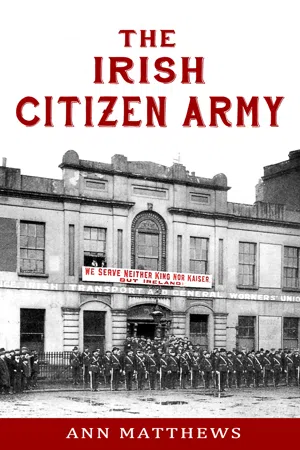

The Irish Citizen Army

About this book

The Irish Citizen Army was originally established as a defence corps during the 1913 Lockout, but under the leadership of James Connolly its aims became more Republican and the IRB, fearing Connolly would pre-empt their plans for the Easter Rising, convinced him to join his force with the Irish Volunteers. During the Rising the ICA was active in three garrisons and the book describes for the first time in depth its involvement at St Stephen's Green and the Royal College of Surgeons, at City Hall and its environs and, using the first-hand account of journalist J.J. O'Leary who was on the scene, in the battle around the GPO.

The author questions the much-vaunted myth of the equality of men and women in the ICA and scrutinises the credentials of Larkin and Connolly as champions of both sexes. She also asserts that the Proclamation was not read by Patrick Pearse from the steps of the GPO, but by Tom Clarke from Nelson's Pillar. She provides sources to suggest that the Proclamation was not, as has always been believed, printed in Liberty Hall, and that the final headquarters of the rebels was not at number 16 Moore Street, but somewhere between numbers 21 and 26.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

From Defence Corps to

Citizen Army, 1913

In his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History, Thomas O’Donoghue, a member of the ITGWU, said that ‘when the 1913 lockout strike took place, the workers were really hopeless, and one means of keeping up their enthusiasm was through marches of the Pipers’ Band’.1 He recalled:

One Sunday (I think it was the first Sunday of the strike) we were coming from Liberty Hall to 77 Aungier St. and, on turning into South Great Georges Street, some commotion took place at the rere of the band and I gave the order to halt in a very loud voice, I called over the Superintendent of the police and asked him for his name. I told him I’d hold him responsible for any breach of the peace that took place; that we were merely marching, as we had a right to do, through the city, and we did not need police protection.2

Later that day, Bob de Coeur called a meeting of the members of the Aungier Street branch and proposed that men should be provided with hurleys to act ‘as a bodyguard for the band’.3 Charles Armstrong, a reservist of the Royal Irish Rifles, was appointed to drill and train the members and was assisted by a man called Kearns, who was an ex-member of the Dublin Fusiliers.4 From that day a bodyguard was provided whenever necessary and they ‘had no more police interference’. The men were then trained to ‘act on whistle signals only’ and they operated by walking alongside the marchers, carrying hurleys and acting as a protective barrier.5

These men had effectively organised a defence corps that accompanied strike demonstrations and marches. On 28 September 1913, when the first of the food ships sent to Dublin by the BTUC docked, The Irish Times reported on the scene at Sir John Rogerson’s Quay and noted:

Quickly the food ship was made fast. And just at this moment a couple of hundred Transport workers, wearing picket badges and carrying sticks, marched down the quay under the command of Councillor (William) Partridge. They set about their function of maintaining order, and it must be admitted that they discharge it well.6

William Partridge, who commanded the bodyguard of men, was the secretary of the Inchicore Branch of the ITGWU.

In late October James Connolly wrote in The Irish Worker:

We know our duties as we know our rights, we shall stand by one another, through thick and thin, prepared, if necessary, to arm and achieve by force our place in the world, and also to maintain it by force.7

While threatening to use force may seem provocative, a case could be made that when Connolly made this announcement, he did so in the context of the fast-evolving Volunteer movement, instigated in January 1913 by the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). This movement had its origins in the wake of the presentation of the Third Home Rule Bill for Ireland in 1912, by British Prime Minister Herbert H. Asquith. The Bill was passed by the House of Commons, and although it was rejected by the House of Lords, under the terms and conditions of the Parliament Act 1911, this would simply serve to delay its enactment by two years.

While nationalists greeted the prospect of Home Rule with enthusiasm, for unionists the Bill threatened disaster. Under the leadership of Edward Carson, their first call to action came in the form of a document entitled ‘Ulster’s Solemn League and Covenant’, in which they pledged to use all means necessary to defeat Home Rule, including physical opposition. The Ulster Unionist Council inaugurated the Ulster Solemn League and Covenant in September 1912, and approximately 200,000 men signed it. The UVF was subsequently established in January 1913 with membership limited to those men who had signed the Covenant, estimated at 100,000. The UVF was formed to convince the British people that Irish unionists were vehemently opposed to Home Rule, an idea further promoted in September when:

Upping the stakes, on 24 September 1913, 400 members of the Ulster Unionist Council met in Belfast, appointed a commission of Five headed by James Craig in consultation with Edward Carson to frame and submit a Constitution for a Provincial Government for Ulster … which would come into operation on the day of the passage of any Home Rule Bill.8

The Freeman’s Journal reported:

It would be more correct to say that the members of the Ulster Unionist Council, having first constituted themselves the Central Authority of the Provisional Government, proceeded to delegate their powers to the standing committee of the Ulster Unionist Council.9

In response, Eoin MacNeill, a prominent Irish nationalist, published an article on 1 November 1913 entitled ‘The North Began’, in which he said that southern nationalists should form their own volunteer force to put pressure on the British to keep their promise of Home Rule.

On 10 November The Irish Times reported that the UVF had enrolled 2,000 members in Dublin. The following day a steering committee met to plan the setting up of the Irish Volunteers.

While all this was going on James Larkin successfully appealed his prison sentence and was released on 13 November. That evening a torchlit rally was held by the ITGWU at Liberty Hall to celebrate his release and it was at this rally that James Connolly instigated the creation of the Citizen Army. In his speech, he stated:

I am going to talk sedition. The next time we are out for a march I want to be accompanied by four battalions of trained men with their Corporals and Sergeants. Why should we not train our men in Dublin as they are doing in Ulster?10

Connolly continued, saying that ‘every man who was willing to enlist as a soldier in the Labour Army should give in his name when he drew his strike pay’, and he would then be informed ‘when and where to attend for drilling’.11

Four days later, Connolly announced that this new force had competent officers to instruct and lead it, because there ‘is a necessity of having trained battalions of men’, and he again asked that all who were willing to join the ‘Citizen Army’ would hand in their names for drilling and training.12 The Evening Telegraph reported that he said:

If we had a disciplined body of men there would be less danger of any of them falling against a policeman’s baton. He hoped to see them soon on their route marches with their pikes on their shoulders … they had been promised the services of a competent military officer, the son of the distinguished Irish general who defended Ladysmith in South Africa during the second Boer War.13

That distinguished Irish general was Field Marshal George White. The son of whom Connolly was speaking was Captain Jack White and he, too, was a hero of the Boer War, having been awarded a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) medal for his bravery in fighting the Boers. In all of the literature relating to the founding of the Citizen Army this information about Captain Jack White is generally omitted. This blind spot can perhaps be attributed to the fact that a mere thirteen years earlier the anti-Boer War Irish Brigade 1899–1902 had been supported by Arthur Griffith (the founder of Sinn Féin), Maud Gonne and James Connolly through the Irish Transvaal Committee. Tellingly, a memorial arch to Irishmen who died serving with the Dublin Fusiliers in South Africa, built in 1904 and located at St Stephen’s Green, was given the derisory name of ‘Traitors’ Arch’ by nationalists. Thus, pointing out that White had received a British military honour for his role in the war would have been a sensitive point.

How a man of impeccable unionist and British military background became involved in the cause of Irish Labour in 1913 is interesting. Captain White wrote his autobiography in 1934, calling it Misfit, a very apt title for a man with an eccentric personality. He was born James Robert White at Whitehall, Broughshane, County Antrim in 1879, into a family that was Church of Ireland, staunch unionists and members of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. Jack was educated in England, first at Winchester public school and later at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. At the age of eighteen he was serving with the 1st Gordon Highlanders and embarked with them from Edinburgh Castle for South Africa at the outbreak of the Boer War in 1899. His father was the colonel in charge of the defence of Ladysmith and succeeded in holding that town when it was besieged by the Boer Army. In 1901 the colonel was rewarded with the governorship of Gibraltar and his son Jack was appointed his aide-de-camp. Discontented with army life, however, Jack resigned his commission in 1907 and then drifted through several jobs and situations, appealing to his father for money when he needed it.

White returned to Antrim sometime in 1912 and was opposed to the sentiments of Edward Carson and the setting up of the ‘Provisional Government’ by the Ulster Council. A protest meeting was held at Ballymoney on 24 October 1913 to express opposition towards ‘the lawless policy of Carsonism’ and speakers were invited to express ‘their views freely and frankly’.14 White took this opportunity to do so, and other speakers on the platform included Sir Roger Casement and the historian Alice Stopford Green. Subsequently, White was invited to speak...

Table of contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 From Defence Corps to Citizen Army, 1913

- 2 The Second and Third Phases of the ICA, 1914–1915

- 3 Preparation for Revolution

- 4 Rebellion

- 5 ‘The Republican Flag Floats over its Centre: O Destiny of My Country! Quo Vadis?’1

- 6 The Courts Martial

- 7 The Power of Money

- 8 Decline 1917–1921

- 9 Civil War and its Aftermath 1922–1927

- 10 Demise

- 11 R. M. Fox and the Muffler Aristocrats

- Appendix 1 Irish Citizen Army Membership, 1916

- Appendix 2 ICA Boy Scouts, 1916

- Appendix 3 Women’s Section ICA, 1916

- Appendix 4 Female Members of the South Dublin Unit 1920–1923

- Appendix 5 Members from the War of Independence Period to the Civil War

- Appendix 6 Women in the ICA

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- About the Author

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Irish Citizen Army by Ann Matthews in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Irish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.