![]()

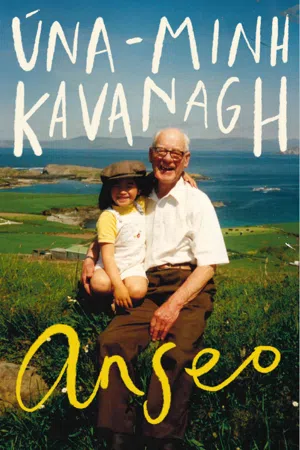

‘Where Are You Really From?’

I’ve had more than my fair share of racism and general ignorance in my life. From the casual racism by a taxi driver or shop assistant to being jeered at and shoved in the street, it’s all game for some people. Apart from it being obviously problematic and nasty, the underlying effect of having to deal with the same insults and questions again and again is extremely frustrating because I’ve grown up all my life knowing I’m Irish – not Irish-Vietnamese, not Vietnamese – simply Irish.

You shouldn’t judge by appearances

Ní hionann i gcónaí an cófra is a lucht

Meeting new people can be … interesting. I smile and I’m polite and I feel like they’re just waiting for me to say something they consider ‘non-Irish’ so they can interrupt with, ‘AH HA! So, you’re clearly not really one of us’. Their desire to ‘catch me out’ has made me wary of strangers and new situations. Since my early college days, I’ve learned how to prepare myself for new surroundings and people. But that in turn burns a lot of my own energy so then it’s even more exhausting having to prove something as inherent and undeniable as my Irish identity. Only in Ireland – my home! – am I a curiosity, no matter how many times I’ve spoken publicly about my identity.

Taxis are very often the scenes of this nonsense, passed off as casual banter. As a result, I try to avoid them now. After hopping in and confirming that, yes, indeed I am the person they were meant to pick up, the conversation starts with that most innocent of questions:

‘Oh, where are you from?’

‘Oh I’m from Kerry,’ I respond, knowing exactly what is coming next. As the conversation moves on, the driver becomes more probing and less polite. They glance between my reflection in their rear-view mirror and my name on the taxi app.

‘Úna-Minh Kavanagh … Yeah, but where are you really from?’

‘I’m from Kerry but I’m a freelancer so I work around the country.’

‘Yes, but, where are your people from?’

‘My people? Well my Mom is also from Kerry and a lot of my family are from the Gaeltacht.’

‘And was learning another language easy since, you know …?’

‘No I love Irish, it’s great, my grandad spoke to me in Irish all the time.’

And on and on and on.

I’m no fool, I know that what they’re really asking is: why are you brown? It’s not that people of colour are hypersensitive to or offended by being asked ‘where are you from?’ It’s the lack of acceptance dressed up as incredulity that is ridiculous and rude. We’re just so tired of having to explain ourselves and our heritage all the time, especially because people don’t take our first answer – where we are from – as the truth. Would I lie to you? My partner, who is a white Irishman is never probed about where he is really from when we’re in Ireland. My mom is never asked, nor was my grandad asked either. I lived in Dublin for ten years of my adulthood, a city where people from all across the world have made their home, and yet I was regularly on the receiving end of the belief that being white automatically means you’re Irish. This discrimination grinds a person down and I’m not unique in feeling this. Indeed, the director of the European Network Against Racism (ENAR) Ireland, Shane O’Curry, put it well when he described how the ‘drip, drip, drip effect’ of casual racism turns ‘corrosive’ and wears on the person. Oh, I can relate.

I’m only human

Níl ionam ach duine tar éis an tsaoil

By the time I started working as a journalist in Dublin at the age of twenty-one, after completing my degree in 2012, I had become used to hearing racial slurs thrown at me. I was working on Capel Street where I could frequent a Brazilian shop, an Italian café, a Korean Barbecue, a Japanese restaurant and even a Vietnamese café called Aobaba. The street felt safe and I was spoiled for choice when it came to seeking lunch options. No one looked at me twice. I went to Aobaba frequently to savour its Vietnamese menu, food which was familiar to me after some recent trips to Vietnam. But when I left that street for the rest of the city, I needed to avoid hassle and I did that by putting on my headphones, dipping my head down and walking on. I could be doing anything or nothing – walking down Henry Street, hanging out in St Stephen’s Green or getting a takeaway with my mates – and some dope would yell at me something stupid like ‘What’s the craic Miss Ping Pong?’

A year later, I had had enough of the slurs, all I wanted to do was go about my daily business, not feeling on the defence all the time. And so there I was, on a rare, sunny Thursday in May, standing on Parnell Street minding my own business, after another day at work and looking at my phone. I had spotted the group of young people, about ten or so teenagers, coming towards me from across the street and had consciously dipped my gaze to the screen, my default diversion tactic. When I looked up, it was just in time to hear one of the boys shout at me:

‘You’re a fucking chink.’

Once again I found myself bored and irritated having to defend myself. It was a sunny day in early summer, I was paying them no attention, why couldn’t they just leave me alone? I reacted quickly, without thinking, without politeness, exhaling an exasperated, ‘Oh, fuck off!’ But as I spoke, the one who had shouted at me grabbed my face with his right hand and yanked at it. I stumbled out of shock and the force of it. Then he spat in my face.

Utter humiliation.

The gang moved on, all laughing and giving each other playful arm jabs. They left me to wipe the spit off my face and hair. I stood alone, phone in hand, my stomach churning with shame, fright and anger.

No one came to my aid.

On one of the busiest streets in our capital city, not a single person nearby asked if I was okay. An older white man, sitting in a taxi about a metre from me, looked away when my eyes met his. All of those people around me saw exactly what had gone down but they walked on. I guess you could call this a prime example of the ‘bystander effect’, where multiple people see an incident and think someone should get involved but everyone waits for someone else to do something first and, in the end, no one does anything. I was absolutely furious to experience this first-hand. If you’re wondering what they could have done differently, I can tell you that simply asking, ‘Are you okay?’ or ‘Is there anything I can do?’ goes a long way in the aftermath of such an attack. I needed empathy in that moment but the strangers around me made me feel like I didn’t matter.

I had never gone to the Gardaí before about any racist incidents, because I always thought I’d be wasting their time. Ireland has the highest rates of some hate crimes in the EU, but no proper hate crime laws to address it, a statistic I was aware of for years and had, like many others, simply accepted. Why bother? I’d often think. These kinds of crimes were not in the news or on social media then like they are now; over the years I had learned to absorb racism silently and alone. I tended not to share most of these racist incidents with my mom because I didn’t want to upset her even though I knew she would be in my corner. I didn’t want her worrying about me. But on this day I walked home to my apartment in Stoneybatter, my mind on overdrive with a new purpose. As I reached the bottom of the stairs in my building, I gripped the bannister and took a breath. I was sick of dealing with this on my own. There and then the whole notion of ‘céad míle fáilte’ and the apparent friendliness our country prides itself on became a gross lie to me. I thought that if I, an Irishwoman and a person of colour, was getting this crap, what on earth were the immigrants to this country and our tourists receiving? I needed to do something about it.

I called the Gardaí at Store Street Garda Station a few hours after the attack and managed to get the words out. Even though my grandad had been a Garda, I had never had any dealings with them myself so I was a bit fearful going into an unknown situation. One of the first questions the Gardaí asked after taking my initial statement was:

‘Why did you wait until now to report it?’

I’m sure it was just a standard question, but it threw me off. I felt like they were almost saying to me, ‘Well clearly it wasn’t too bad if you left it for a while before you rang us up.’ But if I’m being honest, I also felt kind of silly approaching an authority like the Gardaí when they could be dealing with something I considered to be much more serious. I felt shame and guilt. A group of young, ignorant boys racially abused me and one of them spat at me. I was the adult in the situation. I was still standing and wasn’t physically hurt. I began to question whether it was a real crime at all. But sometime after making my statement to the guards, and the more I thought about it, the more I realised I should not have felt silly or embarrassed to report this aggression towards me. Keeping quiet about it, literally keeping my head down and not reacting, would allow it to keep happening to me and to others just like me. I thought of the man in the taxi who wouldn’t meet my pleading eyes and how this inaction confirmed my worst fears: people just don’t believe it happens. Or, worse, they wilfully choose to ignore it even when it’s right in front of them.

We have the right to speak out

Tá sé de cheart againn labhairt amach

So, having made my report to the guards, there was no way I was just going to sit around waiting for justice. Me being me, I posted my anger about the whole thing on Twitter and within minutes the reaction was loud and clear: horror mingled with an immense show of support. I just wish I could have had that response when I was standing there on the street on my own. Don’t get me wrong, I value my online life, but there is still something better and more comforting about someone asking if you need help in real life. After that attack, I could’ve done with a hug and a cup of tea, not just a tweet.

In the weeks following the attack, using my own influence, I was able to push the story extensively, both online and off, to many media outlets. I was determined to show that I would not stand idly by simply taking it. I was on ‘Ireland AM’ and ‘Midweek’ on TV3 (now Virgin Media One); I wrote a piece for The Irish Times and The Kerryman; I was featured on The Journal.ie, Today FM, RTÉ Radio One, Newstalk and my own regional station, Radio Kerry. I also wrote a blog post that was viewed over 75,000 times. I was even interviewed for The New York Times. David Conrad, a PhD student, had spotted my story and wanted to write about what it meant to be Irish in Ireland today, as well as discrimination here. This unexpected international attention was a boon as it gave more gravitas to the story, one that could now be reaching Irish-Americans. All of this coverage and attention transformed an extremely negative and upsetting experience into a positive one. The scale of it made me realise the strength of my own influence and reach, but also that I had a power I wanted to use responsibly. Despite some of my introvert tendencies, I was truly delighted to get my message through all that social media noise. This really was the moment when I took activism seriously. In a strange twist of fate, it was the catalyst I needed. My actions helped to raise awareness of racism in Ireland and, in turn, it forced open a conversation on the whole concept of Irishness. Because most people understood and agreed that what that boy did to me was wrong, what they hadn’t thought about before was the fact that not every Irish person is white. That young thug had made the false deduction that what a person looks like is the equivalent of how that person identifies. Little did he know just how well connected I was and how much louder and stronger my voice could be.

Derek Landy

@DerekLandy

Everyone show their love for @unakavanagh, an Irish girl who was racially abused in Dublin. For taking a stand, Una ROCKS.

Itayi Viriri

@itayiviriri

Replying to @unakavanagh

@unakavanagh @IrishTimes ~ Well done for not taking this ignorant crap anymore! Too many of us do & that’s wrong! Hopefully not any more!

Laura

@TheDublinDiary

Replying to @unakavanagh

@unakavanagh I read your blog post with my class of inner city learners yesterday, they were quite horrified, we talked at length about it.

~ fionnuala ~

@babyeatyrdingo

Replying to @unakavanagh

@unakavanagh @IrishTimes Too few people excuse racism as ‘humour’ in Ireland – thank you for speaking up and exposing the reality of it.

And finally, there was this comment on my original blogpost from my amazing mom:

A minority, however, accused me of pulling the ‘race card’, eventually concluding, ‘Ah sure, they were only messing’. One such absolute amadán decided to write to me anonymously:

I didn’t bother responding to this smugachán (arsehole). Waffle like this only reinforced my reasons for amplifying my story so firmly in the media in the first place. These racists can only consider being Irish as one thing: white, and if you don’t fit into that description, you’ll always be ‘foreign’ and therefore bad and ‘other’. ‘Playing the race card’ is, in fact, a deeply harmful statement used to silence people of colour who dare to speak about their own, true experiences of racism. The race card just isn’t a thing. Let me be very clear, I speak about racism because I’ve experienced it first-hand and the last thing I want to do is compete with anyone else on the aspects of it that matter most. A ‘race card’ suggests a kind of privilege or free pass yanked out by people of colour in order to win an argument. Things could not be further from the truth. Where the privilege actually lies is in not having to think about race issues, ever. This is not a game and I’m no...