This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

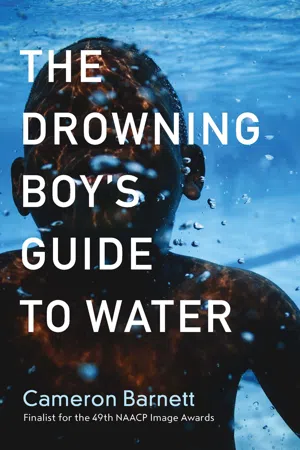

The Drowning Boy's Guide to Water

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Cameron Barnett's poetry collection, The Drowning Boy's Guide to Water (winner of the 2017 Rising Writer Contest), explores the complexity of race and the body for a black man in today's America.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Drowning Boy's Guide to Water by Cameron Barnett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatur & Poesie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

III

THE BLACK BOY’S GUIDE TO BLACKNESS

In this town, rock salt purples the snow;

cold air too thick to see each other

downtown, amid the poor and busy

following the purple to avoid

stepping on toes. Elsewhere, an army

widow lights a cigarette, watches

the snowman in her yard begin to

melt. In her hands, a box full of her

husband’s letters. Another puff—soon

the box will be bursting with ashes.

At the high school, a black boy thumbs through

an old copy of August Wilson’s

Fences. He feels the spotlight coming

when the teacher asks the class to read

parts—no one likes to say the word, but

all want to hear it. At the bookstore,

a skeptic buys a bible before close.

He takes his purchase to the corner

of the café and he reads, surprised

at how small and many the words are.

In this snow-strapped town, the raw air grinds

with gritting teeth. Purple-footed folk

breathe hard and step carefully on by.

The cross-eyed bible reader squints for

the truth. A widow turns to ash all

that had been steel in her. In this town,

the black boy stands before his class, says

Nigger right into their eyes, then sits.

MEMOIR OF A PLAGIARIST

I wrote Hamlet in a summer, Moby Dick in a year, mastered loss,

and penned “Prufrock” on a rainy day. My love told me stories

were just masks of words, all guise no guts. Once I conquered literature

I moved to music: “Auld Lang Syne” and “Amazing Grace,” “The Star-

Spangled Banner” for starters. Sometimes I didn’t know my next song

until somebody sang it first—but I wrote it, lyrics like a signature

everyone recognized but nobody knew was mine. My love told me

songs were just earrings. When they no longer sufficed I moved on

to building, stacked silver to the sky and called it Chrysler, built

a bridge so strong my lover named it Brooklyn—each time I carved

my name in the nooks where no one noticed. I learned so many things

could be secrets, but my love told me a secret is just the valley

between a truth and a lie. Soon building was easy, so I started stealing

light everywhere it fell, balled it up, hurled into the night and made Aries,

Aquarius, Pegasus, Pisces, the Pleiades. I slept at my love’s side,

crescent clutch under the sky I’d sewn. When she told me the people

in her dreams were made of clay I didn’t believe her, so I became a dream,

rewired neurons until her nights were a seamless cinema. But I forgot

a perfect story isn’t perfect until it finds its flaw. My love forgot me—

I became a thin sliver in her mind, more waning than waxing;

a needle threading itself to light, unlooping every time.

SMOKE

When my uncle fought fire he didn’t use a hose

like his father before him—he used a straw

to sip orange juice and watched the sun flicker

between the curtains each morning. He fought

fire all his life in the hospital, though bedridden.

Dad used to tell me He has a hard time with things

the rest of us do everyday. I never did meet him,

but I knew his good and bad days by my aunt’s

crow’s feet or how Dad’s knuckles rolled under his skin

when they came home from visits and played Art

Blakey in the living room so loud I couldn’t hear

them talk, I never questioned why

I couldn’t see him. I never asked if I could.

In a hospital I pass often, my uncle scales a ladder

and leaps through flames, taking an ax to every locked door.

I don’t yet know that the house is him, that something keeps

rekindling the fire every time he puts it out. If one can say

a house is the space just above your throat, the whole thing

furnished basement to attic and burning, I can imagine

my uncle leaning deep in his rocking chair, embers spread

around him in a big lagoon, the pick of his ax-head blunted,

kissing his heel as it slides from his lap, and just outside the window

his brother and sister waving their bodies wildly to fight

the fire too, and that after a lifetime it might be hard

not to see them as candles.

My aunt tells me he saw my graduation pictures once and gave

something that looked like a smile. I learn where the thyroid is

when cancer comes for his neck and threatens to finish

where the flames are failing. In the end, it’s not the fire that kills.

Once in a while I’ll walk home and look up to see smoke

coming from the next neighborhood over and I wonder

if I might be watching someone’s death not too far from me.

It happens most often in spring right before it rains

and the smell of what’s lost falls all afternoon.

I turned down giving my uncle’s eulogy

because they buried him in a jar

and I didn’t know the right words

to make a good first impression.

Tonight I’m writing you a letter, Bruce, though it’s winter now

and Dad is filling the fireplace with logs from the woodpile

even though the chimney may be too cold for the smoke to rise.

BETWEEN SKIN

Suppose I say the word “autumn,” and write

“satchel” on a small blank notecard, lick it

closed in an envelope and mail it to you

so as you open it, standing alone in your cold

kitchen, you recall crimson leaves crunching

under our feet, the smell of the steep city trail,

how we split clammy palms long enough

for a love note to slip beneath the red-patched flap

of your bag, the corners of your grin pinned back

with hesitation, our shoes kicking up the dirt.

Or would you remember on...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- I

- II

- III

- Notes on Cameron Barnett

- Acknowledgments