What has changed, then? It is not the attention to crime. Rather, a tough-on-crime era arose, beginning in the 1970s and ascending into prominence in the 1980s. This era ushered in unprecedented emphases on punishment over rehabilitation and, in particular, intensive use of incarceration. Put differently, the quality and quantity of punishment changed. The country turned away from rehabilitation and toward incapacitation and deterrence as the way to reduce recidivism. It turned, too, toward retribution and the development of an ever-expanding array of strategies for achieving it. Social exclusion rather than inclusion of those who offend constituted the “new penology.” 2

In some ways, the logic seems simple and straightforward. If rehabilitation does not work—as the famous Robert Martinson report, published in 1974, suggested—and if crime stands to overrun society, recourse to no-nonsense punishment should be pursued. 3 And it should “work.” That is, it should signal to all Americans the country’s moral code. It should reduce crime rates by educating would-be offenders about this code and simultaneously by scaring them away from even considering a criminal lifestyle, a mechanism typically referred to as general deterrence. It also should reduce recidivism in a similar manner. A tough stint in the “slammer” should induce fear among those released from prison and so induce a specific deterrent effect.

Missed in all of this simple and straightforward logic were the kinds of insights that might have led to a more careful and considered approach to crime control and punishment. Prisons, of course, cost money. Once built, they typically remain in place. Few politicians, for example, can successfully run on a campaign of reducing prison capacity. The potential to be painted as “soft on crime” sits there and, as Governor Michael Dukakis learned in his 1988 presidential campaign, can contribute directly to losing an election. 4 Accordingly, any increase in the capacity to incarcerate should not be undertaken lightly, precisely because it obligates taxpayer dollars almost indefinitely. Put differently, investing in a prison is tantamount to obtaining a mortgage from which one cannot escape.

Finances, however, barely scratch the surface when we consider incarceration. As decades of scholarship now establish, the intensive pursuit of incarceration has created ripple effects of unintended harms that, to date, do not seem counterbalanced by benefits that may have accrued from the investment. This problem, and the need to do something about it, provides the motivation for this book. Any solution, however, requires first understanding the nature of the problem, its causes and contours, and the range of possible strategies for intervening. Simply calling for less incarceration will not suffice. Indeed, it is not appropriate. Crime hurts people. Punishment, including incarceration, stands as a time-honored way to address that harm. But it is not the only or even necessarily the best way to do so.

As we discuss below, the scale of changes in the country’s use of incarceration demands attention. For scholars, innumerable opportunities exist to develop a better understanding of crime and offending. For policy makers, practitioners, and the public at large, the situation is cause both for optimism and for utmost concern. On the optimistic side, numerous opportunities exist for improving punishment policy in the United States. The concern, however, is that the failure to take advantage of these opportunities will result in immediate consequences in the form of more costs, more crime, and more suffering.

Mass Incarceration and Reentry

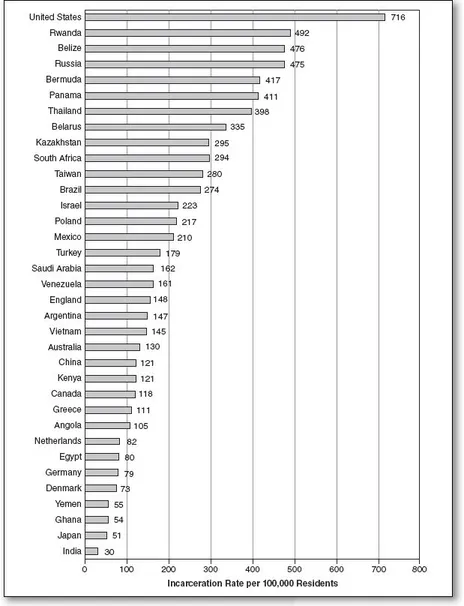

After decades of relatively consistent, low-level increases in prison populations, the United States embarked in the late 1970s and early 1980s on the equivalent of a policy that has come to be called “mass incarceration.” States and the federal government built prisons. Lots of them. And they filled them, so much so that America’s use of incarceration exceeds that of almost all other countries. 5 As inspection of Figure 1.1 shows, after adjusting for population size differences, the United States incarcerates more individuals per capita than any other country in the world. Counting both jail and prison populations, the United States incarceration rate is 716 per 100,000 residents. By contrast, Russia’s incarceration rate is 475, the United Kingdom’s is 148, and Germany’s is 79. The United States stands at the top of this list even if all countries, not just those in the figure, are included. 6 The world incarceration rate is estimated to be 144 per 100,000 individuals. 7

Figure 1.1 International Rates of Imprisonment for Selected Countries

Source: Selected countries from Walmsley (2013). A complete list of countries and updated statistics is available through the International Centre for Prison Studies (http://www.prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief).

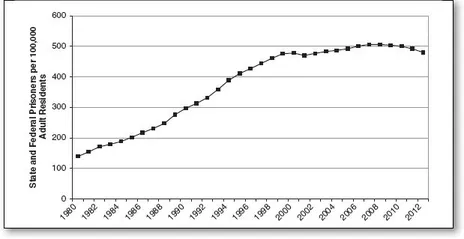

In absolute terms, the number of inmates in state or federal prisons in the United States soared from 500,000 in 1980 to over 2.3 million in the course of just over three decades, with only a slight tapering off in recent years. The increase well exceeded what would be predicted by changes in population and, as will be discussed, crime rates. Figure 1.2 shows that, in 1980, the United States incarcerated 139 individuals in state or federal prisons per 100,000 adult residents; by 2012, that rate increased to 480. (International comparisons typically include jail populations, hence the higher United States incarceration rate shown in Figure 1.1.) Put differently, over this time span, incarceration rates increased by approximately 250 percent.

Figure 1.2 Incarceration Rates in the United States, 1980–2012

Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics (2000); Carson and Golinelli (2013a, b); Harrison and Beck (2006).

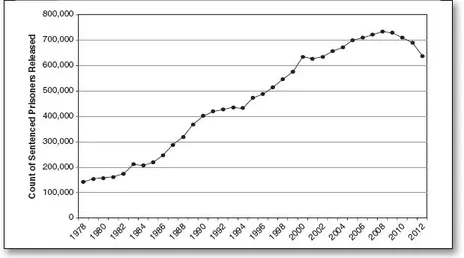

During this same time period, the correctional system, which includes individuals on probation, in jails and prisons, and on parole, expanded from 2 million to over 7 million individuals. 8 For example, probation populations increased from just over 1 million to well over 4 million. 9 The reentry population grew, too, despite lengthier terms of incarceration. Nothing short of life sentences for all inmates can change the fact that, in general, over 93 percent of all inmates return to society. 10 The end result, as shown in Figure 1.3, is that between 600,000 and 700,000 individuals are released annually from state and federal prisons back into society. By contrast, in 1980, the country released 154,000 individuals from prison. This steady and dramatic increase in the correctional system occurred for three decades. It did so despite several economic downturns that led observers to speculate that the expansion simply could not continue. But it did. And it left the country in a position where, even with a leveling off or even a moderate tapering of the prison population, a commitment to mass incarceration—and its many intended and unintended consequences—remains.

Figure 1.3 Sentenced Prisoners Released from State and Federal Jurisdiction, 1977–2012

Source: Carson and Golinelli (2013).

Indeed, the end result involves much more than the release of individuals from prison. Release is but the start of a complicated process for ex-prisoners, one that is built on an equally complicated set of practices, policies, and social conditions. The reentry of prisoners into society has far-reaching consequences that implicate not only ex-prisoners but also their families, the communities to which they return, states, and the country. More than a decade of research on reentry highlights this fact and underscores that mass incarceration has imposed, and will continue to impose, substantial costs on society with benefits that remain largely speculative. For example, from 1982 to 2011, total state corrections spending increased from $15 billion to $53 billion in real dollars. 11 That estimate does not reflect the significant increase in costs for law enforcement and the courts or the costs that victims, families, and communities incurred during this period. There are other consequences associated with mass incarceration as well. These include the potential for increased offending or crime rates, declines in neighborhood cohesion and labor markets, and other quality-of-life indicators. 12

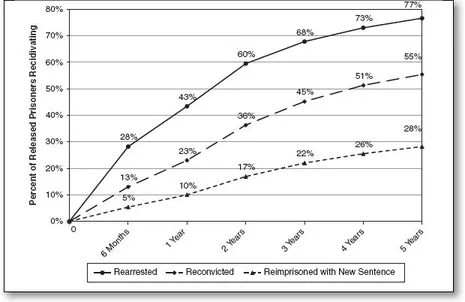

There is no evidence that rates of recidivism declined during the era of mass incarceration. 13 A national assessment of recidivism rates among prisoners released from thirty states in 2005 found that, within 5 years of release, 77 percent of prisoners were rearrested for a felony or serious misdemeanor (rearrest rates did not vary appreciably by type of crime), 55 percent were reconvicted of a new crime, and 28 percent were sent to prison for a new crime (see Figure 1.4). 14 An even more sobering picture emerges when we recognize that over half of prisoners (55 percent) were reincarcerated within 5 years of release; some returned due to new prison sentences while the rest returned due to technical violations (e.g., failing a drug test, missed parole officer appointments, or the like). 15 The initial months after release constitute the period when individuals are most at risk of recidivism: Rearrest occurs for over one-fourth (28 percent) of prisoners within the first six months of release. Thereafter, the likelihood of recidivism increases, but at a slower rate. The high levels of recidivism do not constitute evidence that incarceration worsens offending, but they raise critical questions about its effects. 16

Figure 1.4 Recidivism of U.S. Prisoners

Source: Durose et al. (2014:8, 15).

Other consequences of mass incarceration exist. To use one prominent example—the widespread and increased use of supermax incarceration, including the military’s reliance on the prison facility at Guantanamo after the September 11, 2001, attacks, led to international condemnation of the United States. The emergence and use of supermax housing occurred in the absence of any credible empirical research documenting its benefits. 17 Throughout the book, we will discuss other examples. What we will emphasize here is that the country achieved, in but a few decades, historically unprecedented growth in incarceration. By so doing, it placed enormous demands on taxpayers while simultaneously limiting opportunities both to punish and to promote public safety through other potentially more effective and efficient approaches.

If the benefits of greater use of prison outweighed the costs, there might be cause for celebration, especially if benefits greatly exceeded costs. Yet review of the literature on mass incarceration, reentry, and punishment suggests just the opposite. Research indicates that large-scale incarceration and the more general “get-tough” shift in punishment have harmed communities. They have created or amplified racial and ethnic disparities and tensions and disenfranchised large swaths of the American populace. In addition, although in some places mass incarceration and “get tough” punishment may have modestly reduced crime and recidivism, considerable evidence suggests that elsewhere they have increased crime and recidivism relative to what otherwise would have occurred. 18

That bleak assessment, one found in many scholarly accounts, suggests substantial cause for concern. Perhaps it overstates the case, or maybe it misses the mark altogether. Maybe large-scale investment in incarceration in recent decades needed to happen and created benefits that have yet to be fully appreciated. Is such an assessment accurate? How would we know? These are critical questions that should interest us all—citizen, policy maker, practitioner, and scholar alike. To avoid simplistic assessments requires careful consideration of many facets of mass incarceration and its end result, mass reentry.

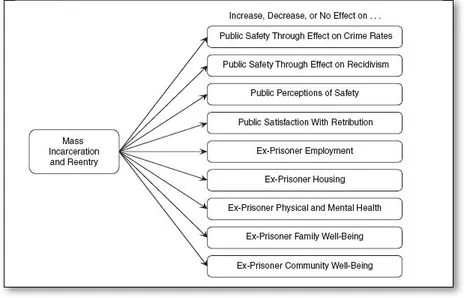

Figure 1.5 illustrates the point. On the left stands mass incarceration and reentry. To the right stand a range of community outcomes that may be affected by them. These include increased public safety through reduced crime rates or reduced recidivism, or both; increased public perceptions of safety, which may or may not directly accord with actual crime rates or incarceration rates; public satisfaction with a central goal of punishment, namely, retribution; and other dimensions that may seem at first blush to lie outside the purview of criminal justice and yet may be affected by incarceration. Imprisonment, for example, may affect ex-prisoner employment prospects and access to subsidized housing. It may affect mental or physical health. It may affect families, who bear additional burdens when individuals leave prison without the possibility of employment and with physical or mental illnesses that place demands on or affect other family members. Not least, it may influence communities in a myriad of ways, from increased crime rates to reduced quality of life. The net sum of the benefits and costs along each of these dimensions ultimately determines whether mass incarceration, or any other approach to punishment and public safety, is effective. 19

Figure 1.5 Mass Incarceration and Reentry—and Why They Matter

Swirling in and around the many considerations that emerge when we investigate such questions are opportunities to pursue avenues of research of longstanding relevance to social scientists. What, for example, are the causes of offending? Historically, the bulk of criminological theory on offending derived from a focus on delinquents and youth populations. With the advent of mass incarceration, a logical shift to understanding offending over the life course emerged, as did theorizing that incorporated insights about changes in psychological and social development and context as individuals age. 20 Studies have turned, too, to e...