![]()

Section 1

Nursery and Primary School Based Forest School

Introduction

This first section looks at how Forest School has developed in mainstream early years and primary settings, as an important part of the curriculum for all children. Practitioners demonstrate why Forest School is not just about remediation and healing, but also about normal growth and development.

![]()

1

Breaking Through Concrete – The Emergence of Forest School in London

Katherine Milchem

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter, I aim to:

- illustrate the challenges facing London and the importance of offering Forest School in the capital city

- describe an urban Forest School in south-west London

- identify areas across London embracing Forest School

- consider ways in which Forest School can be implemented and sustained in London.

This chapter explores how Forest School pedagogy has been adapted to London. With some 1.72 million children living in London (McNeish et al., 2007: 1) and only 4.6% of the capital covered in woodland (Greater London Authority, 2002: 8), it is important to find ways to extend this way of learning outdoors into other natural spaces so that everyone can benefit.

Setting up a sustainable Forest School in an urban space such as London is challenging. London has characteristics that distinguish it from the rest of England. The exact number of Forest Schools in London is unknown. At least 15 out of 32 boroughs in London contain educational settings who have undergone accredited Forest School training and are offering Forest School as part of their educational provision.

Why are Forest Schools Important in London?

Concern that children’s experiences and activity with nature are decreasing, particularly in urban areas (Thomas and Thompson, 2004; Prezza et al., 2005; Tovey, 2007; Louv, 2010), has been expressed in parliamentary debate about education. The State of London’s Children Report 2007 was commissioned by the Greater London Authority by a team of researchers at DMSS Research and Consultancy and at the Institute of Education. This report notes that London has several distinct characteristics which distinguish it from other parts of the country. These include:

- extremes of wealth and deprivation (with particularly high levels of child poverty in inner London)

- highest levels of crowded housing in England

- highest obesity rates in England

- high proportions of pupils with a minority heritage (i.e. black, Asian)

- highest pupil mobility in England (children moving frequently but not by choice)

- lower attainment levels at Key Stage 1 (KS1)

- greatest risk of social exclusion.

Thomas and Thompson (2004) and Tovey (2007) mention that the risks of social exclusion of children living in inner-city areas are higher than those living in suburban or rural areas. According to Thomas and Thompson (2004), these children have far less access to ‘high quality natural environments’ in their communities (Thomas and Thompson, 2004: 11). Natural outdoor spaces, such as woodland, offer a high-quality provision that is difficult to match in a classroom but finding these places in some areas of London is challenging.

UK-based research commissioned by the Forestry Commission and Forest Research suggests that Forest School should take place in a woodland environment. However, research from abroad mentions the benefits of outdoor play and education in natural, wild and open spaces but does not specify that one environment is better than another. The Mayor’s Biodiversity Strategy notes that ‘[t]he seven boroughs along the Thames from Hammersmith and Fulham to Barking and Dagenham, have less than 20 hectares of woodland between them ...’ (Greater London Authority, 2002: 8). The lack of woodland in London denies many residents easy access, so if Forest Schools are limited to woodland, many children living in London and other urban areas will be excluded from participating.

There is cause for optimism; according to London Play’s website, ‘London has more public green space than most other capital cities in the world, which should be prime play space for children and young people’. In London, there are several ‘Sites of Special Scientific Interest’ (SSSI), urban wetlands, chalk grasslands and ancient woodlands; London Wildlife Trust manages 57 nature reserves across Greater London. However, in 2009, Natural England highlighted that ‘... a third of adults, predominantly young adults, low income groups, minority ethnic groups, people with disabilities, and older people and women do not connect with the natural world at all’ (Natural England, 2009b: 1). The problem is exacerbated by patterns of behaviour in family units. Palmer (2007: 76) notes: ‘Sadly the parents seldom do much to widen their young children’s horizons ... in inner cities, many children never visit the great city parks a bus ride away from home’.

In 2009, Natural England commissioned England Marketing to conduct a ‘Childhood and Nature’ Survey (Natural England, 2009a), exploring the contact the children of today have with nature compared to what their parents had. Results showed a worrying trend away from outdoor play, particularly in natural spaces. According to the findings, ‘less than 10% [of children] play in such places compared to 40% of adults when they were young’; however, 81% of children ‘would like more freedom to play outside’ and most parents would like them to be able to but concerns over safety restrict this. Nearly half of the children surveyed stated that they were not allowed to play outside unsupervised and nearly a quarter were worried about being out alone (Natural England, 2009a: 5).

Following on from the survey, Natural England has set a target to get ‘One Million Children Outdoors’ over a three-year period. Their aim is to achieve this through different projects including farm visits, trips to nature reserves, green exercise programmes, walks and the development of Forest School education. Children are naturally curious about the world around them but it is how their curiosities are accepted or rejected that helps to shape their later experiences. Not all parents and educators recognise the value of exposing their children to natural environments. Research suggests, many reasons for this: fears for safety, lack of accessibility, cultural differences, but also adults’ own early childhood experiences will influence how much exposure to natural spaces they give children (Natural England, 2009; Munoz, 2009).

Figure 1.1 A leaf pit

Setting the Scene for an Urban Forest School

Case Study 1: Michael’s visit to an unfamiliar environment

Michael is four years old. His mother has told the staff that he is a chatterbox at home; however, when he is at Nursery, he is quiet. At Nursery, Michael spends most of his time playing outdoors but prefers to be a silent observer in group activities. On his group’s first Forest School session, the children explored the site, walking over bumpy, grassy terrain with lots of leaf debris on the ground. Michael stopped while everyone else continued on ahead of him. He was quietly crying. When asked what had happened, he did not answer. He just looked down at his feet. When asked if his wellington boots were hurting his feet, he shook his head. He then pointed to the ground; it was the ground itself that was distressing him. He was asked if he wanted to hold an adult’s hand and he nodded. The adult showed him how to lift up his feet to walk over the land. It became apparent that some children are so accustomed to walking on flat, manicured lawns, concrete and safety surfaces that the experience of walking on uneven natural terrain is foreign, very hazardous and, for some, can be truly frightening. Three months on, Michael still prefers to hold an adult’s hand when walking on certain terrain; however, he has developed a stronger degree of comfort in being in a natural environment. He shows a greater ability to identify risks and, with encouragement, he is showing more independence in being able to manage them.

When considering setting up a Forest School, it is important to be sensitive to the needs and insecurities of children, parents and colleagues as some will be less comfortable in outdoor learning environments. The length of time it takes for a colleague to become comfortable in taking children to natural spaces will depend on their own experiences and exposure to outdoor spaces and the amount of training and support they receive. The length of time it takes a child to become comfortable and independent at Forest School will depend on their age, development, needs and the amount of exposure they have to natural spaces at school and at home. Practitioners need to be able to recognise when it is appropriate to push children beyond their comfort zone to broaden their experiences and further their learning and development. In our experience at Eastwood, it is often the children who express a dread of going out to Forest School who need and benefit from it the most.

In March 2010, Natural England and the Forest Education Initiative commissioned Eastwood Nursery School Centre for Children and Families to deliver a series of Forest School Education Taster Days across London. The aim of these events was to encourage play, learning and teaching in the natural environment and to promote Forest School. These events explore the benefits, challenges and practicalities of setting up a Forest School in an urban setting and highlighted learning opportunities through play and activities in natural spaces. They gave educational professionals opportunities to share ideas and experiences, discuss possible sites in their local community (and beyond), expose challenges and barriers, and come up with possible solutions. It was an opportunity to network with other settings in the borough and to exchange contact details.

Figure 1.2 Mark making with handmade charcoal pencils

At Eastwood, ‘Parents and Parks Days’ and sponsored walks gently change perceptions and attitudes and influence positive changes to lifestyles where needed. Parents and their children are invited on day trips to local parks. Outings are kept as natural and family orientated as possible. Time is spent exploring, playing, relaxing, socialising and eating in the great outdoors. By considering how other cultures use natural spaces, exploring the sort of access provision people want and by making the outings accessible and enjoyable, we can cater to an ethnically diverse population. Parents and younger siblings are invited to participate in Forest School sessions through their key person and family workers. Families are encouraged to share folklore, music, dance, language, crafts, food, knowledge, skills and experience which encompass natural elements. This has led to a strong participation in children’s learning from mothers and fathers.

Evidence suggests that there is a need to look closely at current educational environments and how they might be contributing in the decline in natural outdoor play experiences. In London, many educational outdoor play environments are limiting. A lack of greenery, synthetic surfaces, stagnant man-made play equipment and manufactured ‘natural’ areas set in prescribed areas, lead to the environments becoming unchallenging and uninspiring to children and adults alike. With ‘wrap-around care’ being offered in a lot of schools, some children are becoming accustomed to only spending time in these types of environments. According to The State of London’s Children Report, ‘Many children in London do not have easy access to parks or other open spaces’ (McNeish et al., 2007: 20). Children need a balance of experiences in created and natural environments. This will enable them to be autonomous, and to enjoy and gain respect and appreciation for the affordances various environments offer. Defries (2009) states that at the Nursery World Outdoor Play and Learning Conference in London, 170 delegates noted that ‘... practitioners’ lack of understanding of outdoor play emerged as the biggest barrier’ to developing better outdoor learning provision.

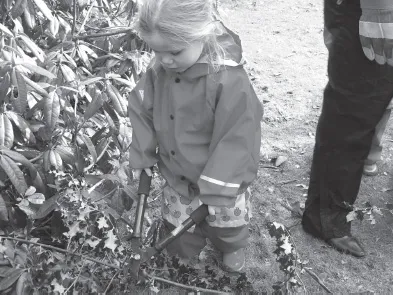

Figure 1.3 Using tools

Organisations and initiatives such as Forest Education Initiative (FEI), Groundwork, the Woodland Trust (Nature Detectives), BBC Breathing Places, Growing Schools, Natural England and London Play are all working to improve outdoor play and education provision outdoors for children and young people, provide information and educational support, and promote events through their websites. The United Nations marked 2010 as the International Year of Biodiversity (IYB), to help children understand and appreciate the rich biodiversity on earth and the connectedness between ecosystems through first-hand experiences in natural environments. Children who have played in natural spaces are far more likely to develop a deep desire to protect the natural living systems which provide us with fuel, food, health, richness and other essential services. Forest School is an effective way to develop children’s pro-environmental values and behaviours. Up-close and personal encounters with the natural world will better equip practitioners and children to find ways to scaffold these experiences and create opportunities for discussion and sustained shared thinking, building pupils’ awareness of the environment and desire for sustainability....