Ways of Viewing the World

It is human nature to try to explain what we observe occurring around us, a process that people engaged in long before physical, biological or social sciences were established as disciplines. The difference between ‘common sense’ explanations and scientific ones lies in the way the two originate. Everyday observations are haphazard, careless and not systematic, whereas those carried out by scientists endeavour to be specific, objective, well focused and systematic, to the extent that they could be replicated by someone else. So what difference does it make in the long term? If we were just to sit around passively and contemplate life, it might not matter on what basis explanations were derived. In reality, however, decisions are made about people, objects and events, often on the basis of explanations of why things happen, and extrapolations as to what would happen under certain circumstances. Incomplete or even incorrect explanations lead to poor if not disastrous decisions, whether they be about bridge construction, social conditions in high-rise apartment blocks or the effects of stress on individuals. While there are few true guarantees, the more systematic and organized the studies we conduct, the more likely they will produce valid explanations that can be used to support decisions.

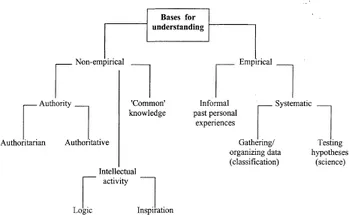

In the social sciences, achieving a thorough understanding of a situation often requires constructing a model of events and how people interact. The acquisition of information to support such a model may come from a number of sources, some of which will be more organized and systematic than others. In some situations what is needed is sufficient understanding to make a sound decision, while in others the goal is more academic, the refinement of an elaborate model. Figure 1.1 outlines a simplistic way of considering the processes employed for understanding the world around us. In reality, final choices, decisions, judgements and model building are usually based on the simultaneous or collective employment of more than one of these, though there may not be a conscious effort to include more than one.

This view of building understanding and decision-making introduces a variety of concepts, some of which will be more familiar than others. All of them, though, are in need of defining if an appreciation of how this book proposes to contribute to the realm of developing an ordered view of the world is to be achieved. The first division, if you like, is between empirical and non-empirical approaches – basically a difference between directly collecting information from outside ourselves, and using indirect sources, vicarious experiences and introspection. As will be seen, there are situations where all of these unavoidably come into play when decisions are made, and entire courses of study cover individual approaches. This book is no exception in that it can only focus on a limited area and enhance the development of appropriate skills.

Empirical Approaches

Figure 1.1 Foundations for Understanding

To lay a foundation for considering primarily the branches on the far right of Figure 1.1, empirical systematic, we need to have a common understanding of terminology. Empirical indicates that the information, knowledge and understanding are gathered through experience and direct data collection. Daily we gather information just through contact with others and our environment, but it is not necessarily intentional or conscious, and usually not very systematic. Thus it is not difficult to miss events or to observe them in an inappropriate context. The police have a difficult time finding reliable witnesses to crimes or other events, since people just do not know what to look for and are not trained to do so in stressful situations. Systematic observation implies that we know what type of event we are expecting to see, though not necessarily the actual outcome. Identifying a 20-year-old actor dressed as a 70-year-old woman in a shopping mall is not as easy as it may seem, particularly if you do not expect to encounter such a person. A trained observer might succeed where the casual encounter would result in a perfect deception. Yet as will be seen, there is more to it than just observation and classification when the issues become more complex. The emphasis in this text will be on techniques that enhance one's ability to make systematic observations and use these as part of the process of testing guesses (hypotheses) about how events can be described. Such an approach is usually described as scientific because of its systematic approach and goal of producing replicable studies, but this does not necessarily divorce it from humanity nor simply reduce people to the status of numbers on a computer file.

Non-Empirical Approaches

Non-empirical sources of information include forms of introspection, vicarious experiences and other people's analysis of events. Like empirical sources, some of these are more valid as a basis for understanding and decision-making than others. For example, when we refer to an authority, the source may be someone who issues instructions that must be followed regardless of the reason why (authoritarian) or someone who expresses a position on the basis of vicarious and systematic first-hand experiences (authoritative). You may consider the university to be authoritarian for dictating that you must take a particular course for your degree, but the teacher to be authoritative because of his or her knowledge and experience in the subject. You accept what is presented in a course as truth, even if it is based upon someone else's experiences. Vicarious learning is necessary if for no other reason than there is not time to learn everything first-hand. We may accept that wholewheat bread is ‘better’ for us (even if we do not eat it) because someone else has taken the time and effort to demonstrate its benefits.

It is well recognized that ‘common’ knowledge is a significant part of any culture. We all ‘know’ that all lawyers are just interested in making money, politicians lie only when their lips move, and that Scotch is better than rye whiskey. Some statements such as these are more easily verifiable than others, and others are not worth the effort (except possibly to the advertising industry). For example, European cultures tend to value the nuclear family, while in most parts of Africa the extended family is paramount. The issue of an indisputable universal ‘best’ simply does not arise in many situations, since traditions, values and beliefs have evolved over time and are part of that culture. What becomes of interest to the social scientist is the relative truth of some of these – for example, stereotypes of ethnic groups. If it were not for the fact that these have been exploited to the extreme of inciting genocide more than once in the history of humankind, it might be a topic only of academic interest.

The third major source of non-empirical understanding is intellectual, what goes on between our ears. Whole courses are taught about logic, and the world would be quite chaotic without it. Rarely, though, is logic capable of providing complete understanding on its own. As history has shown, in isolation or with limited information some rather bizarre explanations have arisen, such as the flat-earth model. This is not to belittle logic as a way of knowing, but, like all of these, alone it is limited.

At the other extreme are the experiences that fall in the category of inspiration, which could originate from a mystical or religious experience, but could also include others where we gain some sort of insight that governs or changes the course of our lives. What inspires us to choose a career? Is it logic, collecting information, having work experience, or reading about job descriptions and then weighing up all the alternatives? Or how many of us decide in the dark of night because of some inspiration? Most likely it is a combination of information gathering, logic, listening to authorities, and personal inspiration. Religion, political and philosophical commitments, and even choice of spouse, probably result also from this sort of event. The computer dating agency may seem scientific and encourage a logical approach, but in the end why pick one person over another? People have gained insight or altered their views through mysticism or inspiration triggered by such varying experiences as listening to music, reading religious tracts, viewing scenery or talking to someone. While such experiences provide personal insight, they are difficult to share and are limited in their value as a common source of understanding that can be shared across a wider audience.

Integrated Thinking

Let us return to an integrated view of thinking in social sciences for a moment, having dissected the basis for understanding and classified the parts. Consider, for example, cultural values and their interaction with government policy, and recall from recent history a rather extreme but real case. We all have relatives, regardless of which our society values more, the extended family or the nuclear family. In recent years, China has tried to contend with an exploding population by having a policy (authority) of one child per family. An interesting logical consequence of this will be that after two generations, there could be no aunts or uncles. What will be the long-term impact on family, society and culture? To answer this question, does one depend only on

- logic (if no uncles, then …),

- ‘common’ knowledge or informal past personal experience (I know someone whose parents were only children, and they …) or

- a more systematic gathering of experiences and testing of hypotheses?

One would hope that policies imposed as a consequence of economic, political and environmental needs would have been researched in terms of potential outcomes, based on comprehensive models of society, social interaction and personal development. Sources of understanding in such situations could be based on empirical systematic studies of contemporary societies, combined with the consideration of past parallel situations (vicarious learning), and perceived values of those whose culture will be changed. Yet history is littered with cases where this has not been done, or the flawed models on which decisions are made have been untested, poorly tested, or in some cases based solely upon one source of understanding alone. The consequences have frequently been unfortunate for the targets of actions based on such representations of reality.

One Corner of the Chart

As noted earlier, this book will focus on one corner of Figure 1.1, on empirical systematic approaches, with some concern for gathering, but primarily with the aim of testing hypotheses in equations where there are quantitative data. In light of everyday experience with people and the study of human activity, one other goal of this text should be expressed at this point. While it is human nature to want to be ‘right’, the rather grand aim here is to provide the skills with which one is better equipped to pursue the ‘truth’. This has the disconcerting consequence that sometimes when resolving issues, our preferred view of the world may not be shown to be the best or most accurate. As human beings, it hurts to admit that we are somehow wrong. The story is told of a physics professor who commented to a class that he regretted doing his Ph.D. at a certain university because the research team pursued the ‘wrong’ model of the nucleus. He believed that had he gone elsewhere and worked on the ‘right’ model, his efforts might have been recognized. The unfortunate aspect of models is that they are rarely right or wrong, but dynamic (ever changing) and often have a limited life (until a better one comes along).

It is no different in the social sciences. The pursuit of the truth is desirable, but often this constitutes trying to develop a model of reality, an explanation of events employing abstract and intangible concepts. Have you ever seen poverty? Not likely, but you may have seen the consequences: poor health, inadequate housing, etc. Have you ever seen an electron? Neither has any physicist, though we all use electric lights to read by. Even with such well-established models for describing why electric light bulbs give off light, the physics community would be willing to consider alternatives were they to be presented. Human nature being what it is, though, it is usually easier to achieve acceptance of new models after the originator (and his or her disciples) have passed on to the big research room in the sky. To assume such a position, ideally one must be more like a judge in a court looking for the truth, rather than a lawyer trying to prove he or she is right.

While focusing on the systematic pursuit of truth, we will obviously draw upon other sources of understanding in Figure 1.1. ‘Common’ knowledge provides us with views of the world to test for accuracy which will be combined with the expectation that any study is logically consistent throughout. Since time is limited, other authorities will be consulted for vicarious experiences and previous developments. Now let us consider a more formal way of describing the nature of explanations and how their validity can be enhanced.

Theories, Laws and Information

At the foundation of the process of trying to understand events and their causes are observations, which necessarily must be distinguished from inferences. From a distance, we see a man walking erratically down the street and could infer that he is drunk or on drugs, is ill with a nasty virus, or has had a stroke and lost some of his co-ordination. If we approach the man, additional observations will allow us to decide which inference is the most accurate. In more systematic research, we often wish to infer the existence of a mental state based on observations. For example, is seeing a smile sufficient evidence for inferring the existence of a state of pleasure? It might be in very small children, but in adults, who are much more sophisticated in their social interactions, the smile and ‘Have a nice day!’ greeting may be more of a wish than an existing state of mind.

As part of understanding the world around us, we engage in classification of people and events, sometimes with the intent of judging, other times just for the sake of knowing where they fit in our personal scheme of things. That was a good film, a handsome lad, an attractive blonde, a poor person, a tedious lecture. These often constitute potential variables, non-constant traits, which allow us to consider the possibility of relationships. Is there any relationship between the clothes worn and the perception of ‘handsomeness’? Do blondes have more fun? What contributes to poverty? Data gathered as a result of such questions might result in verifiable relationships – for example, people who live in poverty tend to have parents who also lived in poverty. Fashionable clothes may tend to make men appear more handsome than they would in less stylish apparel. From such results, laws may be formed that describe relationships among variables, but these may not describe causality. Also, since they describe isolated variables, they do not give a very complete picture, which is not surprising since rarely are events so simple as to be completely explained by one simple law.

To provide a more complete explanation of events in ours lives, theories – models and explanations that elaborate on why events have occurred – are devised to describe causal relationships between actions and/or events. These may involve a number of laws – relationships among variables – that appear to influence events. The value of a theory is in its ability to allow us to explain and predict outcomes, though often it can be found to be incomplete. Gathering supporting evidence to extend the applicability of a theory to all possible situations is not feasible for many reasons. The main limitation is simply one of scale: it is unlikely that a single study could cover all the relationships in all the situations described by a theory of any consequence. Many research studies, therefore, are tests of limited subsets of relationships to allow for maximum control over unwanted variables, to avoid ethical problems, and/or simply to contend with the difficulties of using human subjects. One challenge to the researcher is to ensure that the study of a component of a theory fits like a puzzle piece in order to enhance its impact on the theory as a whole.

As our understanding of a given s...