- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Kafka's Prague

About this book

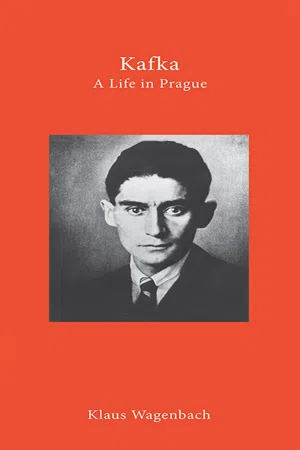

Nearly one hundred years after Franz Kafka's death, his works continue to intrigue and haunt us. Kafka is regarded as one of the most significant intellectuals of the nineteenth and twentieth century, and even for those who are only barely acquainted with his novels, stories, diaries, or letters, "Kafkaesque" has become a term synonymous with the menacing, unfathomable absurdity of modern existence and bureaucracy. While the significance of his fiction is wide-reaching, Kafka's writing remains inextricably bound up with his life and work in a particular place: Prague. It is here that the author spent every one of his forty years.

Drawing from a range of documents and historical materials, this is the first book specifically dedicated to the relationship between Kafka and Prague. Klaus Wagenbach's account of Kafka's life in the city is a meticulously researched insight into the author's family background, his education and employment, his attitude toward the town of his birth, his literary influences, and his relationships with women. The result is a fascinating portrait of the twentieth century's most enigmatic writer and the city that provided him with so much inspiration. W. G. Sebald recognized that "literary and life experience overlap" in Kafka's works, and the same is true of this book.

Drawing from a range of documents and historical materials, this is the first book specifically dedicated to the relationship between Kafka and Prague. Klaus Wagenbach's account of Kafka's life in the city is a meticulously researched insight into the author's family background, his education and employment, his attitude toward the town of his birth, his literary influences, and his relationships with women. The result is a fascinating portrait of the twentieth century's most enigmatic writer and the city that provided him with so much inspiration. W. G. Sebald recognized that "literary and life experience overlap" in Kafka's works, and the same is true of this book.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9781907973444Subtopic

Biografías literarias1

Fame – Too Late for the Author

FRANZ KAFKA GAVE US some of the most haunting literary images of the 20th century. The commercial traveller Gregor Samsa in The Metamorphosis, who wakes up one morning to find himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.1 The son who carries out the sentence imposed by his father, and throws himself off a bridge in The Judgement. Young Karl, who blunders through America, much as the elderly country doctor blunders through the ‘unhappiest of ages’.2 Josef K in The Trial, who is arrested despite having committed no crime. The officer from In the Penal Colony who lovingly describes his torture machine. Red Peter, who reports to the esteemed gentlemen of the academy on his past life as an ape. The dead hunter, Gracchus, and his vain search for peace. The futile art of Josephine the singing mouse.

The creator of these images was not a well-travelled man. His life lacked the constant changes of scene that characterise so many writers’ biographies of the 20th century. It lacked the long journeys, the formative experiences and their consequences. It lacked important encounters with fellow writers. Kafka did not even know many of his most important Austrian contemporaries. He knew their work, of course – he was an enthusiastic if unsystematic reader – but he excluded himself from literary discussions. At best he was a monosyllabic and reticent listener to such conversations. He usually sent his manuscripts to periodicals and publishers only when invited to do so, and he limited his contacts to a select few friends. It was an essentially provincial existence – a ‘local’ one, like that of the Austrian novelist Adalbert Stifter (1805–68) or the Irish poet W B Yeats (1865–1939).

Franz Kafka was born in Prague on 3 July 1883, rarely left his native city (and then only for brief periods) and, after a short life of almost 41 years, was buried there at the Straschnitzer Friedhof (Strašnice, now usually called Olšany cemetery). For 14 years he worked as a lawyer for the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia, although he regarded his ‘scribbling’ in the evening or at night as his ‘sole desire’.3

The prose written by this Prague Jew outside office hours gained international recognition only after the Second World War. Kafka’s fame began with a small circle of German literary experts in the 1920s. He was especially promoted in France, first by André Breton (1896–1966) and the group involved with Minotaure magazine, later Albert Camus (1913–60) and Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–80); and eventually Kafka became established in Britain and America. It was not until the 1950s that his work ‘came back’ to German literature, when the first ‘official’ German Collected Works appeared in the early years of that decade. And it was not until 1957 that the first Czech translations were published in Prague, the city that Kafka had put on the literary map. The first Russian translation of his work (‘In the Penal Colony’) appeared in 1964. Only 40 years after the author’s death in 1924 could it be said that his work was being read all over the world.

The facts about Kafka’s life were not known until much later, even though he lived during the entirely transparent final three decades of the Habsburg monarchy and the first years of the Czechoslovak Republic. This was due not only to the fact that his life was inconspicuous, but also because of the political events of the years from 1933 to 1945. These years, above all, concerned his writing: at the beginning of the 1930s, during a search of the Berlin flat of Dora Diamant (the companion of Kafka’s last years), the Gestapo confiscated a number of manuscripts, which must now be considered lost. The first collected edition of his work, begun in Germany in 1935, was obstructed and then prohibited. Far worse events followed the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Nazis: Kafka’s three sisters were deported to a concentration camp and murdered – a fate shared by many of his relatives and friends. Archives were destroyed; documents were lost; witnesses of his life were killed.

In 1957, when I first visited Prague, I was faced with a sad yet consoling picture: the image of an undamaged city, one of the most beautiful in Europe, but also a very confused picture. On the one hand, almost all of the buildings in which Kafka lived or worked have survived – the Kinsky and the Schönborn Palaces, the Minutá House, and the Oppelt House, the houses at Bilková 10, Zeltnergasse (Celetná) 3 and Lange Gasse (Dlouhá) 18, the office building at Pořič (Na Poricí) 7, and the little house in the Alchimistengasse (Zlatá ulička). The same is true in provincial Bohemia, in Wossek (Osek), Podiebrad (Poděbrady), Triesch (now Třešt), Schelesen (now Želízy) and in Matliary in Slovakia. On the other hand, time and again my search for documents ended in plundered archives; my search for surviving witnesses almost always ended in a room of the Jewish Town Hall on the Maiselgasse (Maislová ulice), the walls of which held shelves filled with hundreds of card indices containing individual red cards listing first name, surname and place of birth – all invariably bore the same rubber stamp: Oświęcim – AUSCHWITZ.

2

The Son of a Shopkeeper, Lost in Prague

KAFKA HAS NOT CONTRIBUTED MUCH to the illumination of his everyday life, even though his diaries and letters – in total almost 3,000 pages – are more extensive than his literary work. His only major autobiographical statement is the ‘Letter to his Father’ from his later years (1919), a vain attempt ‘to reassure us both [Kafka and his father] a little and make our living and our dying easier’.1 However, Kafka’s desire in this letter to ‘reassure’ his father – who viewed his son’s writing with suspicion and incomprehension – led him to falsify many of the facts, and Kafka himself, a year later, referred to the ‘lawyer’s tricks’ of this letter.2

His other autobiographical remarks are less dishonest, but there are few of them and they are mostly no more than marginal comments of self-criticism. Only once does Kafka speak of his ancestors:

In Hebrew my name is Amschel, like my mother’s maternal grandfather [Amschel or Adam Porias], whom my mother, who was six years old when he died, can remember as a very pious and learned man with a long white beard. She remembers how she had to take hold of the toes of the corpse and ask forgiveness for any offence she might have committed against her grandfather. She also remembers her grandfather’s many books which lined the walls. He bathed in the river every day, even in winter, when he chopped a hole in the ice for his bath. My mother’s mother [Esther Porias] died of typhus at an early age. From the time of this death her grandmother [Sara Porias] became melancholic, refused to eat, spoke with no one. Once, a year after the death of her daughter, she went for a walk and did not return – her body was found in the Elbe. An even more learned man than her grandfather was my mother’s great-grandfather, Christians and Jews held him in equal honour; during a fire a miracle took place as a result of his piety, the flames jumped over and spared his house while the houses around it burned down. He had four sons, one converted to Christianity and became a doctor. All but my mother’s grandfather died young. He had one son, whom my mother knew as crazy Uncle Nathan, and one daughter, my mother’s mother.3

Strangely enough, there exists a kind of companion piece to this diary entry by Kafka – two hand-written sheets by his mother, on which, some 15 years after her son’s note, this woman of 77 (in 1932) provides a brief biography:

My dear deceased husband came from Wossek near Strakonitz [Strakonice]. His father was a big, powerful man. He was a butcher, but did not live to a great age. His wife, my mother-in-law [Franziska], had six children, four sons and two daughters. She was a delicate, hardworking woman, who, despite all trouble and difficulties, brought up her children well and they were the only happiness in her life. My husband was sent away as a boy of 14 and had to fend for himself. In his 20th year, he became a soldier, rising to platoon leader. In his 30th year, he married me. He had set himself up with modest financial means and, since we were both very hard working, made a respected name for himself. We had six children, of whom only three daughters are still alive.

Our eldest son Franz was a delicate but healthy child. He was born in 1883 and died on 3 June 1924. Two years later we had another little son, who was called Georg. He was a pretty, vigorous child and died of measles in his second year. Then came the third child, again a boy. He died of an inflammation of his middle ear at barely six months. He was called Heinrich. Our three daughters are happily married and all three live in Prague.

I was born in Bad Poděbrad [Poděbrady]. My grandfather, my mother’s father, was an educated man with a Jewish education. Name of Porias. He was a devout Jew and a well-known Talmud scholar. He had a successful drapery shop in Poděbrad, which was greatly neglected because grandfather preferred to busy himself with the Talmud. The grandparents had a fine single-storey house on the Ringplatz [now Staroměstské náměstí]. The shop was on the ground floor and the best room on the first floor was filled with all kinds of scholarly books. Grandfather was a highly respected man and died at a ripe old age. He had, as I heard in my childhood, two brothers. One of them was very religious. He wore the tassels of his prayer shawl over his coat, even though the school children ran after him and laughed at him. They were reprimanded at school and the children were strictly instructed by their teacher not to bother the holy man, or else they would be very severely punished. In summer as well as in winter he went bathing in the Elbe every day. In winter, when there was a frost, he had a pickaxe with which he hacked open the ice in order to submerge himself. The third brother of my grandfather was a doctor and had had himself baptised. My mother was the only child of the eldest, the religious Talmud scholar. She died of typhus aged 28, leaving, in addition to myself who was only three years old, three brothers. My father married again after a year, and by the second marriage there were my two brothers. One died in the war [in] his 60th year, the other is a doctor. As my brothers were all away, my parents sold the house, and also the shop, and moved to Prague.

My second mother [Julie] died 12 years ago at the age of 81; my father two years later at the age of 86. Father was born in Humpoletz [Humpolec], worked as a cloth-maker and married my mother, who received the house in Poděbrad and also the shop as a dowry.

Father had four brothers and one sister. The brothers were rich people, they owned several textile factories, instead of Löwy they were called Lauer and had been baptised. My father’s youngest nephew was the owner of a brewery in Koschieř [Košíře]. He was baptised and was also called Lauer instead of Löwy. He died in his 56th year. I had five brothers. The eldest lived many years in Madrid as the bank manager of two railways. He was a highly respected official, had many decorations and was esteemed by all who knew him. Because of his position he had been obliged to be baptised. He was single and died in 1923 and was buried in Madrid. My second brother is a businessman, the third was abroad for many years, to wit 12 years in the Central Congo, in China and in Japan.4

It is significant that Kafka, in his diary entry, mentions only the ancestors on his mother’s side: their inherited traits were clearly dominant in him. Also, it was the maternal ancestors of his mother that lived in the small Bohemian town of Poděbrad. Among them, time and again, we find pious scholars and rabbis living a retiring existence, a few doctors, and numerous bachelors and eccentrics, often regarded by their community as odd, often with the delicate constitution that Kafka inherited. His mother’s paternal ancestors, on the other hand, belonged to the textile families common in Bohemia and Moravia, ‘enlightened’ people of moderate Jewish Orthodoxy.

Kafka’s maternal grandparents clearly reflect the religious divergence of the times: grandfather Jakob Löwy was ‘assimilated’, while grandmother Esther came from a strictly observant family. After bearing her fourth child, Esther (as Kafka’s mother reports) died of typhus, in 1859. Yet the suicide of Esther’s mother reported by Kafka was probably caused by other factors as well: Jakob Löwy remarried a mere year after his first wife’s death, and this may have led Esther’s mother (Kafka’s great-grandmother) to take her own life. Therefore, the mother and both grandparents of Kafka’s mother Julie (born in 1856) died early, and from her fourth year she grew up under the care of her stepmother and her father. This second marriage produced two sons, and the lives of the six siblings once more reflect the peculiarity of this family.

Julie’s eldest brother, Alfred (Kafka’s ‘Madrid uncle’) remained a bachelor and eventually rose to become the manager of a Spanish railway company. Another brother, Josef, likewise emigrated: he worked for a large Belgian colonial company in the Congo and in China, married and later lived in Paris (after which Kafka referred to him as his ‘Parisian uncle’). The third brother, Richard, became a merchant, led an entirely unremarkable life and had three children. The stepbrother, Siegfried (Kafka’s favourite uncle), was a peculiar eccentric, a fresh-air fanatic, educated, well-read (he was the only one in the entire family to possess a large library), witty, ready to help and benign, though outwardly he appeared to be ‘a little cold’.5 He remained a bachelor and became a country doctor in Triesch (Třešt), Moravia, where Kafka later often visited him. The second stepbrother, Rudolf, likewise a bachelor, lived a retiring life as an accountant in the Košiře brewery. He was the oddest and most private of Kafka’s uncles. He converted to Catholicism and, as Kafka recorded, progressively developed into an ‘indecipherable, excessively modest, solitary, and yet almost loquacious man’.6 Some of these qualities were also very marked in Kafka himself, especially the shy, almost over-anxious modesty, his timidity, and a certain poverty of human contact. ‘Touchiness, a sense of justice, restlessness’,7 is how Kafka characterised the inherited Löwy traits.

By comparison, Kafka’s paternal heritage was slight. His father, Hermann, was born in 1852 in Wossek, southern Bohemia, a tiny village of scarcely a hundred inhabitants. Hermann came from a humble background: his father, Jakob, was a butcher. In 1849, rather late in life, at the age of 35, Jakob Kafka married his neighbour Franziska Platowski. Apparently, this delay had something to do with a change in the marriage laws. Until 1848, when Jews were granted certain basic rights, only the eldest child in a Jewish family could marry. After 1848, there was a general drift of Jews from provincial Bohemia to the more ‘liberal’ towns. For this reason, when Jakob died 40 years later, he was the last Jew in his native village. He had six children, two daughters and four sons; they became merchants, or married merchants, in Strakonitz (Strakonice), Kolin (Kolín), Leitmeritz (Litoměřice), Schüttenhofen (Sušice) and Prague respectively.

The Kafka family lived in extremely modest circumstances. All of them, while still very young, had to take meat to the neighbouring villages in a handcart, early in the morning, even in winter, and often barefoot. Their house was a type of cottage common in Bohemia, barely higher than a man, and consisted of two ground-floor rooms with low ceilings, in which the family of eight lived. Schooling, given the circumstances, seems to have been above average. Wossek then still had a Jewish school – a remnant from when the village had a large Jewish community – where Kafka’s father, who in those days spoke primarily Czech, presumably learned to read and write German. Even so, it was only a basic education: the letters of the 30-year-old Hermann to his fiancée contain numerous mistakes and their style is clearly modelled on a letter-writing guide.

At the age of 14, Hermann Kafka left Wossek to seek his fortune as an itinerant trader and travelling salesman, evidently with some success. After his military service, he moved to Prague and within a few years set up a fashion accessories shop, no doubt with financial help from his more affluent bride, Julie Löwy, the daughter of a brewer.Footnote: 1 The Kafka ‘will to life, business and conquest’8 was very strong in Hermann, more so than in his brothers, who were ‘all more cheerful, fresher, more informal, more easygoing, less severe’.9

Hermann Kafka never forgot his difficult youth, continually reminded his children of it, and considered social recognition the only worthwhile aim in life. In the old Austro-Hungarian provincial capital of Prague, it was only possible to achieve real social status by gaining access to the narrow German-speaking upper class. (In 1900, of the city’s 450,000 inhabitants, only 34,000 spoke German.)

For a man like Kafka’s father, this was no simple j...

Table of contents

- Kafka

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Fame – Too Late for the Author

- 2. The Son of a Shopkeeper, Lost in Prague

- 3. What does a Boy Learn at an Imperial and Royal Secondary School?

- 4. University, Society and Language in the Capital of Bohemia

- 5. ‘Description of a Struggle’: the Insurance Official, his Job, his Plans and his Journeys

- 6. The Only Way to Write!

- 7. Life or Literature? Kafka’s Engagements and The Trial

- 8. The Wound

- 9. A Naked Man among the Clothed

- Footnotes

- Notes

- Further Reading

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Kafka's Prague by Klaus Wagenbach, Peter Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.