![]()

CHAPTER 1

Who’s in CONTROL?

‘Tell me where is fancy bred, Or in the heart or in the head?’

William Shakespeare,

The Merchant of Venice, Act III, Scene 2

It’s clear that something in the body is responsible for coordinating all it does. Some part of us obviously controls sense perceptions, motion, automatic functions such as breathing, and provides the emotional and intellectual activity we assign to our minds. But there’s little to link these functions with the brain or even to suggest they are all carried out by the same organ. For this reason, it was not immediately obvious to our ancestors that the brain performs these functions.

An athletic manoeuvre such as this demands a lot of the brain as well as the body.

Heart v. brain

Many early cultures associated emotions and thought with internal organs. But there is no physical evidence in the body that helps us to locate emotions, personality or consciousness, so they have been linked with different body parts by different cultures. In Mesopotamia, 4,000 years ago, the heart was thought to house the intellect, while the liver was considered the centre of thought and feeling, the womb of compassion (obviously men were not compassionate) and the stomach of cunning. In Babylonia and India, too, the heart was king.

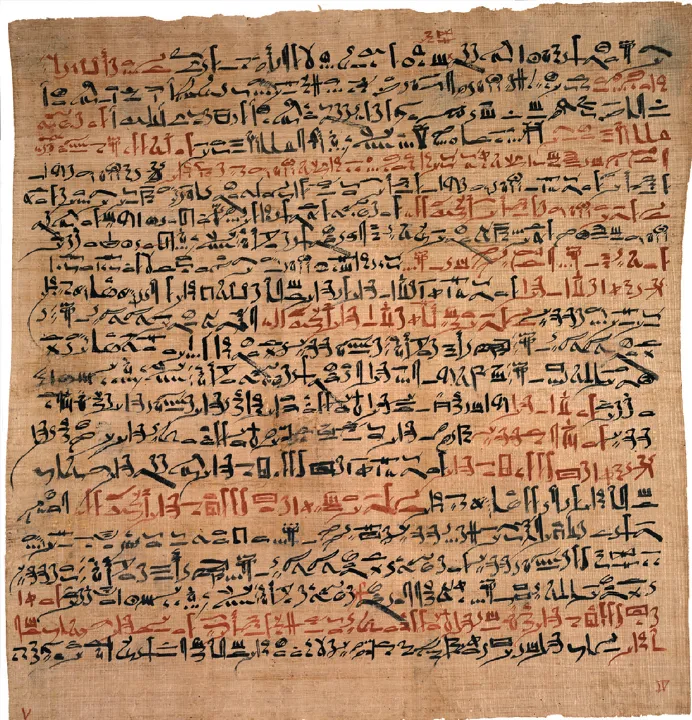

The Edwin Smith papyrus preserves Egyptian medical lore which probably dates from around 2700BC.

First brains

The Ancient Egyptians were at one point aware of the brain’s importance in controlling the body. The earliest known medical text is the Edwin Smith papyrus, produced around 1700bc but probably based on material 1,000 years older. It provides descriptions of 48 cases of injuries, aiming to guide the surgeon in determining whether to attempt to treat a patient. The surgeon realizes that if the neck is broken the patient can become paraplegic or quadriplegic as the connection between the brain and limbs is lost and cannot be restored. The papyrus provides the first ever description of the human brain. It is said to be like ‘those corrugations which form in molten copper’ and that the surgeon might feel something ‘throbbing’ and ‘fluttering’ beneath his fingers like ‘the weak place of an infant’s crown before it becomes whole’.

Even so, the Egyptians were so certain the brain was not a vital organ that they hooked it out through the nose and discarded it when mummifying a corpse, but preserved other organs in canopic jars. Like several early civilizations, the Egyptians considered the heart to be the centre of the intellect and home of the mind.

Perhaps it is hardly surprising that the complex role of the brain was obscure. A bit of post mortem examination reveals the approximate function of most of the major organs. The heart is connected to the blood vessels, the kidneys to the urinary bladder, the gut connects the mouth and the anus by a circuitous route – but it is not at all clear what the brain is for.

Champions of the brain

The brain was first promoted as the seat of the intellect by Ancient Greek philosopher Alcmaeon of Croton in the 5th century BC. He is the first person known to have carried out dissections with the intention of finding out how the body works. He dissected the optic nerve, and wrote of the brain as the centre of processing sensations and composing thought. Around the same time, medical writer Hippocrates also assigned considerable power to the brain: ‘I am of the opinion that the brain exercises the greatest power in the man. . . . The eyes, the ears, the tongue and the feet, administer such things as the brain cogitates. . . . It is the brain which is the messenger to the understanding.’ However, this was by no means the only or predominant view in Ancient Greece.

‘The seat of sensation is in the brain. This contains the governing faculty. All the senses are connected in some way with the brain. . . . This power of the brain to synthesize sensations makes it also the seat of thought: the storing up of perceptions gives memory and belief, and when these are stabilized you get knowledge.’

Alcmaeon of Croton, 5th century BC

The lusty liver

The pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Democritus (460–371BC) divided the functions we now assign to the brain between three organs. He attributed consciousness and thought to the brain, emotions to the heart and lusts and appetites to the liver. Plato (428–347BC) later developed this idea into the three-part soul (see page 18), locating reason or intellect in the brain, which he declared to be ‘the divinest part of us, and lords it over the rest’.

Hippocrates’ treatise on epilepsy, On the Sacred Disease, written about 425BC, cites the brain as the source of pleasure, grief and all other feelings. He says the heart makes sense perceptions and judgement possible and is also the site of madness, delirium and terror and of the causes of insomnia and poor memory.

The Greek philosopher Democritus located consciousness in the brain.

MATTER MATTERS

Democritus taught that all matter is made up of tiny ‘uncuttable’ portions called atoms and that the different qualities of matter come about through the combination and configuration of the different types of atoms within it. The most refined matter was, in his model, made up of the smallest spherical atoms. The psyche (soul or mind) was made up of these refined atoms and concentrated in the brain. Larger and slower atoms predominated in the heart, which he considered the centre of the emotions, and still cruder atoms in the liver, the home of the appetites.

Brain and nerves

The first anatomists to carry out a detailed study of the human brain and to dissect it were Herophilus (c.335–280BC) and Erasistratus (304–250BC) in Alexandria, Egypt. They are said also to have carried out vivisection on human prisoners, a practice defended by the Roman writer Celsus in the 1st century ad: ‘Nor is it cruel, as most people maintain, that remedies for innocent people of all times should be sought in the sacrifice of people guilty of crimes, and only a few such people at that.’

Herophilus is credited with the discovery of the nerves, being the first to distinguish between nerves, blood vessels and tendons (which all look rather similar). It’s possible that he and Erasistratus were aware of the distinction between motor and sensory nerves (see page 86); certainly, Herophilus was aware that damage to some nerves could cause paralysis. They, too, regarded the brain as responsible for thought and sensation, distinguished between the cerebellum and cerebrum, and named both the meninges (membranes surrounding the brain) and the ventricles (spaces filled with cerebrospinal fluid). Herophilus recognized the brain as the centre of the intellect, and placed the command centre in the fourth ventricle. He likened the cavity in the posterior floor of the fourth ventricle to the reed pens used in Alexandria. The cavity is still called the calamus scriptorius (‘reed pen’) or calamus Herophili.

The Ancient Egyptians’ reverence for the heart as the seat of wisdom and the soul lay behind the motif of the ‘weighing of the heart’. After death, two gods, Thoth and Anubis, weigh the heart of the deceased to determine the person’s worthiness (c.984BC).

Herophilus and Erasistratus are the first people known to have worked on the nerves, shown here in a drawing from 1532.

Resurgence of the heart

It might seem that the scene was now set for a steady understanding of the function of the brain to emerge, but unfortunately an influential thinker took a different view. The philosopher Aristotle (384–322BC) was convinced that the heart was the ‘command centre’ of the body, responsible for sensation, movement and psychological activity, whereas the brain served only as a cooling chamber of some kind. He argued against the hegemony of the brain on several counts, most of them inaccurate:

- The heart is connected to all of the rest of the body via blood vessels, whereas the brain has no comparable connections (it has – but nerves ...